Co-Op High School | Arts & Culture | New Haven | Theater

Ophelia pushes Hamlet into a lake, and a fish springs up from between the rows of chairs in a school auditorium. King Hamlet explores purgatory on the sprawling, matte floor of a gymnasium, with basketball hoops in the background. Polonius storms locker-lined hallways with a fizzy intercom spewing words above him. Through it all, a troupe of half-muzzled dancers leads the way, transforming school staircases into Elsinore Castle.

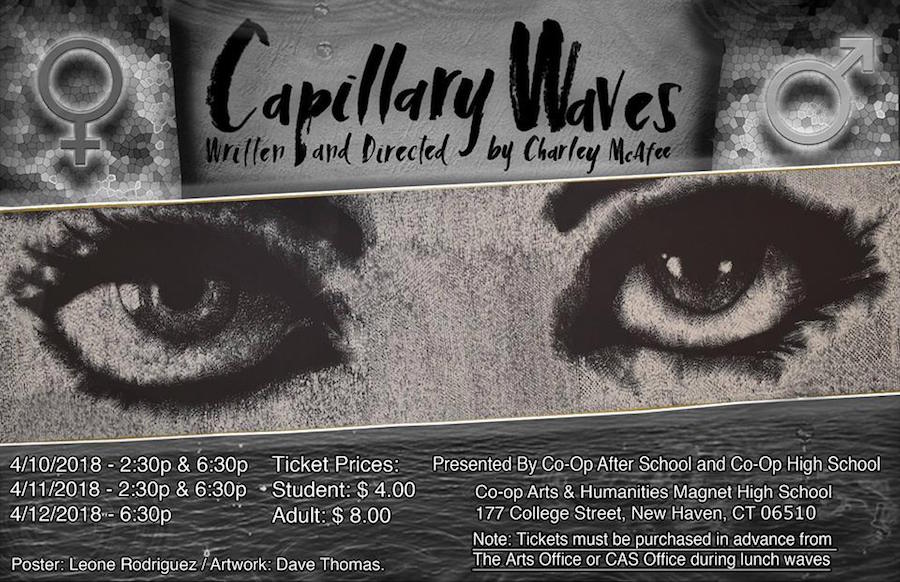

So unfolds the world premiere of Capillary Waves, an immersive and experimental performance at Co-Op High School now through Thursday night. Conceived, written and supervised by Co-Op teacher Charley McAfee, the play opened to a sold out audience Tuesday afternoon. It has repeat performances Wednesday and Thursday at 2:30 and 6:30 p.m.

On its surface, the work cycles through William Shakespeare’s Hamlet, reimagining its female characters as steel-tongued, whip-smart heroines that Shakespeare never quite made them out to be. For McAfee, that process started years ago, when he was cast as Laertes, the son of King Hamlet’s advisor Polonius, and tried to reconstruct the character’s world.

But it got a different source of inspiration when his daughter was born six years ago, and he considered characters like Laertes’ sister Ophelia, lovesick darling of the Pre-Raphaelites. Lovely, insane Ophelia in all her finery, walking herself right out to her watery death. Of the girl driven out of her mind, and left to be discovered upstream among flowers and reeds.

That wasn’t quite how McAfee wanted it to be.

“While Shakespeare wrote many strong, inspiring female characters, I wouldn’t number Ophelia among them,” he wrote in the program notes. “I wanted to have a play where a young woman could play the equivalent role of Hamlet. I wanted to empower my daughter, or my students, to reimagine great works so that they could more easily see themselves in them.”

Capillary Waves starts that on the page, as it retools Shakespeare’s language and the world in which it operates. The early modern padding is intact, but characters have whole new vocabularies to work with—particularly Ophelia (Cristal Arguello) and Hamlet’s mother Gertrude (Audrey Adji). They are stronger willed and more articulate, exposing the society against which they are pushing as they speak.

In one of the earliest and most striking sequences, Ophelia calls Prince Hamlet out on his obstinate male-ness—that which does not allow him to see the good in gender parity. As the two exchange barbs (Ophelia may also throw some shoes and a corset into the mix) she spells out the world in which the two of them live, showing the audience how history will shortchange her before it ever does.

“His most refined weapon to snip her unrefined edges—shame,” she declares as Hamlet reminds her of a woman’s place. The words hang in the air. They are sharp and bitter because they are true.

But that’s just a jumping off point. Characters unfold from there: buffoon-like Polonius (teacher Robert Esposito), twinkle-toed, hot-blooded Laertes (Leone Rodriguez), scheming Claudius, a more delicate Prince Hamlet (Charles Saowski), with a kind of fragile masculinity that begs a closer look. And an Ophelia who has a low tolerance for sexism, and has been trying to find her way around it for her entire young life.

This is where the titular reference—capillary waves, which are usually just called ripples—comes in. From the beginning of the play, water plays a vital role, waves coming up to cloak Fortinbras in their cool embrace, and sweep him back out to sea after he has died. Those waves—a line of women, dressed in black and silenced for the show—absorb his body and so his pain, allowing him to float from this life to another.

They appear throughout the show—funny waves, fishy waves, transitional waves, wave and ripple-like sounds that guide the audience from one act into the next. And no wonder: water has long been depicted as a female element, a life-giving source that is painted and written into backdrops, but carries time forward on its current.

So much of the play’s genius is in its execution—immersive, propulsive theater that uses Co-Op as a backdrop to Hamlet’s Denmark. Starting in a small blackbox, silent actor-ushers guide the audience through the school, easing unfamiliar bodies through doorways, up ramps and staircases, into the cafeteria and gymnasium and dance studio, down hallways where they must line the sides as to let the actors through. Student photography becomes a set piece in one hallway. Bright reminders from the after-school recycling club are spun into another. The library, with its clunky computers and dusty book jackets, seems just right for purgatory.

It’s a view of the school—and its student-turned-actors—from new and intimate angles. The auditorium is a lake, with a tarp draped over the seats and Ophelia and Hamlet straddling its sides and balconies for maximal effect. The cafeteria is Paris, France, her secrets revealed with a few drinks from the vending machine. The gymnasium and library are transformed into purgatory, where computers only play an old-time video of Hamlet in black and white, and no one can hear one’s anguish quite loudly enough.

Lights and props follow characters as they move through the school, casting different colors on the actors as they shift from space to space. In purgatory, it’s the angry red of a festering wound. On the staircase, the green of envy, then the cool blue of water. Audience members look on just feet away, characters sometimes walking beside them, brushing up against their hands, or taking a seat beside them to whisper a monologue.

For instance, in a reimagined sequence on the high school’s second floor landing. Hamlet and Ophelia orbit each other like planets, and the audience sits around them, in chairs that appear out of nowhere. Before them, Ophelia is telling the story of a young girl who sacrifices her life—and her reputation—for her father’s freedom. Hamlet simultaneously launches into a remixed “To Be Or Not To Be” soliloquy, whispering madly to members of the audience as he runs through it again and again. It is impossible to listen to both of them, and impossible not to want to. So you get half of either story.

It is balletic by design. With choreographers Christine Kershaw and Mimi Zschack, McAfee has added physical movement and new spirit guides to literally walk attendees through each performance. Neither Prince Hamlet nor his audience are anchored by the ghost of his father, but by a ghostly Fortinbras (Tymothee Harrell), transformed into a sort of watery serpent after he is slain in the beginning of the play.

It’s Nambi E. Kelley’s Black Rat meets Eden’s much-maligned snake meets the grim reaper, slithering and ssssshhhhh-ing its way to the finish. Harrell, face and neck painted with green and gold scales, is majestic and otherworldly, a radical change from his setting in a midsize urban arts high school.

So too his fellow actors—Polonius, played for laughs in his fur-lined, luxe red wrap and goofy yellow knickers. King Hamlet, whose remorse is palpable as he watches his brother take his life and his title. Ophelia, whose glittery corset, billowing skirts, crinoline, stockings and doll-sized shoes never seem to fit her quite right.

There are moments that sneak up on you with context, testing what you think you know about women, and what the characters know about themselves. In one, audience members are led out of Co Op’s auditorium and up a ramp, at the top of which Gertrude sits in a red evening gown playing the cello. As the audience passes, she looks up, making quick eye contact with the very people that have been watching her play. Behind her, ushers dance in a closed room, their black-clad bodies clear through a wall-length classroom window.

It’s a sort of role reversal, saying, I see that you looked, and I’m checking you on it. She does it again later in the work, as she bursts from double doors and scales a staircase while applying makeup, changing from her skivvies into a bright, swooshing red dress with an uneven hem.

Or there’s an interlude as the dancers/ushers take over the school’s central staircase and begin to dance on it, moving in unison from side to side until you feel yourself lurching with them. Their mouths are muzzled in black, as though they have been shocked to silence. After easing into the same rhythm, they face in, focus on a single body, and watch as she mounts the handrail, and dances from her perch. She will not fall, it seems, because the others simply won’t allow it.

There are Ophelia’s last scenes, as the men in her life tear her down one (Hamlet) after the other (Laertes). Her wide-eyed, tear-covered face gives away all she wants to say about gender roles in the world, both of Hamlet’s Denmark and New Haven’s current high schools.

In each, there is the compulsion to intervene, to tell Hamlet and Ophelia that it doesn’t actually have to be like this after all. That Polonius is a big idiot and no one should listen to him. That Claudius is one big red flag that Gertrude can’t see—or can she?—until it’s too late.

That Ophelia didn’t give “her innocence” to Hamlet, as her brother Laertes puts it, but made a consensual decision to sleep with him. That nothing was lost, because her virginity was never a gift to give someone.

But the audience doesn’t get to. Despite the play’s immersive nature, the fourth wall stays up through a brain-bending end, as Ophelia exchanges one kind of terrarium for another. We don’t know whether to root for her because we’re not sure when the play is over and the actors are just students again.

We are certain, however, that something has shifted beneath us. That there has been a wave, or many, and it has made its mark.