Radio & Audio | Arts & Culture | New Haven

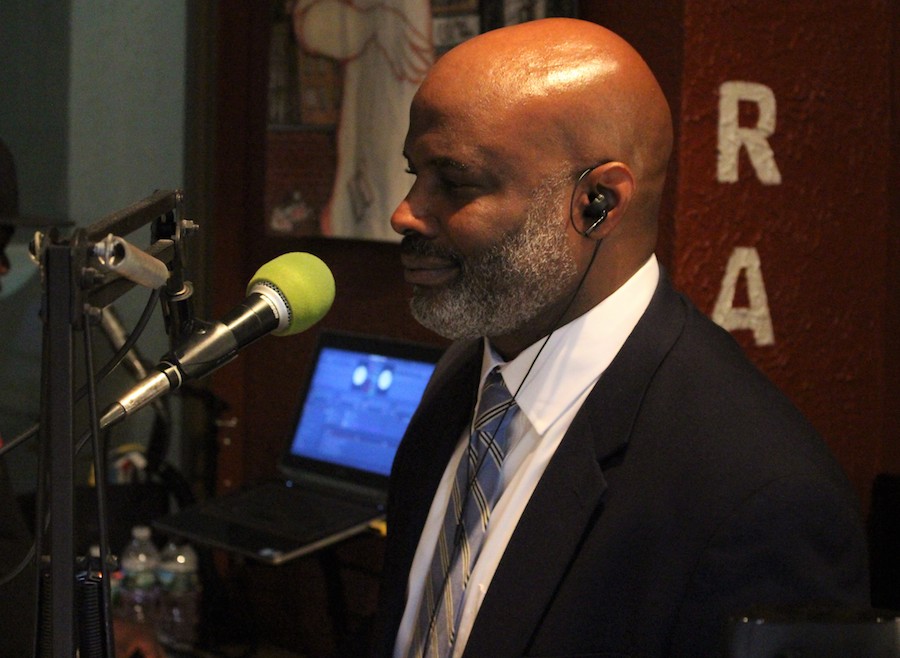

| Thomas Breen Photos. |

Joe Ugly has a message for New Haveners—if you’re going to try something, you might as well do it yourself.

Ugly is the founder and director of Ugly Radio, an independent, internet-based radio station in downtown New Haven that plays hip-hop, R&B, and reggae from independent recording artists across the city, state, and country. Operating out of an intimate, second-floor office space on Chapel Street, he has grown the station from a one-man operation to a part-time and volunteer staff of disc jockeys, musicians, low-key tech geeks, and aspiring radio hosts.

He’s had 13 years to do it, building on his previous experience as a DJ at Ultra Radio. In addition to his work online, he hosts a three-hour drive time show that plays on WNHH Community Radio's airwaves weekday mornings, before Inner-City News editor Babz Rawls Ivy takes the mic at 9 a.m.

Some trappings of the studio are what you’d expect: turntables, microphones, a soundproof recording studio and window decals that mark the spot from Chapel Street. Off to the side, there’s an office where Ugly can do his work. A couch and chairs sit unoccupied, in case anyone on the opening shift—that’s 5 a.m., with an earlier arrival—needs a nap later in the day.

On a recent morning, the space was hopping. Early-morning light peeked in through the window, increasingly bright and warm as the sun climbed. A high-pitched cackle filled the room, followed with full-bellied laughter. DJ Rob Nice was making sure that the independent music kept coming. Longtime volunteer Preston Wilson leaned into a mic to read the day’s local “Ugly Headlines.”

There are quirks like that that New Haveners won’t find on other channels. Ugly has staff read off the “ugly” local, state and national headlines; he invites local guests to talk about the work they’re doing in the city. But what sets it apart, Joe Ugly said in a recent interview, is that the station doesn’t play any music by signed artists.

“A lot of people think that because I only play independent artists’ music … [that] I’m wholeheartedly against record labels,” he said. “[That’s] wrong. I just see room in the game for everybody. Especially with technology.”

But there’s a whole, winding history to that love for independent music, and approach to running a radio station.

Joe Ugly was born in Trinidad, just one in a family of self-starters. As a kid, he remembered watching his uncle pick up garbage with a trolley attachment on his bike. Years passed, and his uncle graduated to a pick-up truck, then an actual truck, then multiple trucks. He eventually became a full-fledged company, laying claim to what Ugly called the biggest trash-collecting service in Trinidad aside from one run by the government.

Ugly immigrated to the U.S. with his family in the 1970s, settling in New Haven’s Newhallville neighborhood and attending Wilbur Cross High School. As a high school freshman during the first wave of hip-hop, he recalled hearing rap for the first time in 1976 at a Labor Day parade in Brooklyn. It sparked his initial interest in the genre, and led him to begin rapping with some of his friends when he got back home to New Haven. By the end of the decade, he was part of a local group that performed around town.

But when he graduated high school, Ugly went into banking. It seemed like a solid enough plan: make good money, have a nine to five. Except he was unhappy. Really, really unhappy.

In the 1990s he decided that he wanted to market rap, and that radio was the best way to do it. He started working with a local radio station and an Urban FM Station, where he not only learned the fundamentals of the business, but saw that working in radio offered him an opportunity to help independent artists. After working as a DJ at Ultra Radio, he started Ugly Radio in 2005. It moved into its current digs in 2007.

Ugly recalled that his brother-in-law told him that if he used the internet for his venture in radio, he would be ahead of the game. But it was the late 1990s to early 2000s —CDs still reigned and dial-up was the fastest standard connection to the web. Streaming music was very much an underground thing. And then there was the simple issue of skepticism.

“When I first started this thing, people were like ‘independent artists? Are you kidding me? Good luck,’” he recalled. “They were laughing … ‘give him three months, he’ll be playing signed artists’ music.’”

“When I first started this thing, people were like ‘independent artists? Are you kidding me? Good luck,’” he recalled. “They were laughing … ‘give him three months, he’ll be playing signed artists’ music.’”

Even after he hit landmark after landmark without caving, he said that, “there were those out there who were literally counting down [to him playing signed artists].”

Instead, Ugly dug deeper into independent artists, discovering unsigned local voices by going around neighborhoods in Connecticut and hanging out in CD shops. Independent artists would put their music in the stores, and then Ugly would walk in and ask the workers, “Who’s the hot indie that you’ve got? Just give me whoever is hot.”

He found about 62 different artists that way in the beginning, which he whittled down to a group of 29 he first started with. He kept up the same practice for several years. But in more recent years, he said that the tables have turned: now the artists have to find him.

He’s received requests internationally from independent artists trying to get him to play their music, but says that if you’re serious about doing music, you wouldn’t let someone who’s thousands of miles away steal your airplay. That you have to do your research and see what’s going on right under your nose.

“I’ve had artists who came here, right out of New Haven, who said, ‘well, you know, I’ve never heard of Ugly Radio,’” he said. “What does that mean? It doesn’t bother me none. If someone in London, England, knows who I am and knows what I do, and you’re right here in New Haven and you’re in the music game and you don’t know what I do, I’m not worried about you. You’re not serious. That person over in England is serious.”

The station, which is now 13 years old, has also made him think critically about music in his adopted country. He said that the American music industry has shown him that U.S. is a “brand-aware nation”—when you enter the music industry an artist, you have to build a brand before you can build a business.

“People like to say that they do music, and they stop,” he said. “But if you do music, so does the guy on the sidewalk with a guitar. He’s just doing music. Now if you want to get paid, that’s a different thing. You’re in the music business.”

Specifically, he said, he’s chosen to play specific genres because “Hip-Hop is about taking nothing and making it into something.” That extends to his faithful crew—people who love radio but don’t always have the technical know-how until they’re in the studio. He said he specifically likes working with Black men in America, who he has dubbed, tongue-in-cheek, “The PTSD Crew.”

“Being a Black man in America and seeing your people get shot all the time on the news is enough to give you PTSD,” he said.

He added that as he sees it, almost every famous hip-hop artist came out of struggle and often dire situations, and many of the new indie hip-hop artists are trying to do the same. Almost all of them think that the only way to turn their nothing into something is to join a record label.

And yet, he said, it’s easier than ever for an artist to be discovered by their fans because of outlets like Soundcloud and Bandcamp.

He added that he’s realistic— he understands that there are “roadblocks” that arise when people are in pursuit of their dreams. Noting his son’s choice to switch from engineering to film directing, he emphasized that sometimes it’s not what one does, but how one does it.

“In order for a surfer to move on that board, he’s got to ride the wave,” he said. “But does he wait for it to get under him, or past him? No. A surfer looks out and sees the swells and positions himself in front of it, and rides that wave to the shore. Most people are scared to get in the water and they see the wave on the shore. But by then, the fun of riding it is gone, and that’s with nearly everything.”

“That’s one of the reasons why I got at the front of the independent game, and I’ll ride this baby to the shore,” he added. “If you are waiting for [the waves] to hit the shore, everyone’s right on it and there’s no enjoyment. It’s lonely out there, it’s dangerous out there, it’s scary out there; but that ride-in is [the] next level. And by the time you get to the shore and everyone’s splashing in it, you’ve got your board at your side, living the life.”