Beth El Keser Israel | Faith & Spirituality | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Westville | Sculpture

Bruce Oren's Ritual, which he sculpted in 1982 and then revisited with mixed media (the leather wrapping and yarmulke, which comes from a Bat Mitzvah he and Angela attended) in 2021. Lucy Gellman Photos with permission of the artist.

The curving marble looks out toward a viewer, flecks of pink, red and orange glistening from its surface. From one angle, a face emerges, wrapped in sturdy brown leather atop a pair of slim, twisting shoulders. At the crown of its head, a gold and purple yarmulke glows beneath the low light. Even in its place beside the men’s bathroom, even with these not-quite-tefillin wrapped wonkily, it feels sacred.

For the artist, the holiest part of making the work may have been the act of carving itself.

Ritual is one of the works in Entropy Warriors, a 50-year retrospective from Beaver Hills resident and sculptor Bruce Oren running at Congregation Beth El-Keser Israel (BEKI) in Westville through Feb. 26. Installed in the building’s first floor and basement, the show traces Oren’s decades-long career, from an unlikely foray into sculpture to his work as an editorial cartoonist, newspaperman, and artist who has made Craigslist a central part of his practice.

The title comes from the idea of making order out of the disorder—the entropy—inherent in the universe. Oren will give a talk on the exhibition on Saturday, Feb. 5; more information is available at BEKI’s website.

Top: Oren in the lower level of the exhibition. Bottom: Documentation of Oren's teahouse, which he has been building in his backyard for over five years. "It keeps stuff out of the landfill and it has its own character," he said of his love for repurposed materials. "I like that."

“It’s essentially what we do as humans,” he said last Tuesday evening, on a tour around the exhibition that jumped from his time at the University of Maryland to years in Houston, Tex. to the teahouse unfolding in his backyard. “It takes, what? A year to build a house? But you can destroy it in no time … Our very beings belie the disorganization of the universe.”

From the moment a viewer walks into the space, Oren both makes sense of and leans into the disorder that is so clearly all around him. On one side of the synagogue’s lobby, his 2007 Embrace of the Angel of Death is so sinuous in its form that it seems to be slowly spinning, caught in the same strange loop that is grief itself. Oren has spent time on every detail—fabric pulled taut in some places and rumpled in others, thick, rope-like strands of hair, the huge, open arms with which one figure absorbs the pain and suffering of another.

Inspired by the death of his mother, it feels of a piece with My Ancestors Were Slaves In Egypt across the room, a three-tiered work in painted limestone that doubles as a self portrait. In Embrace, one figure closes her eyes, her lips resting as if they are in a state of dreaming. Her face, obscured partly by a shroud, seems completely at peace. On the other side of the sculpture, a second face looks pained, exhausted. She tilts her head into the angel’s palm, too tired to fight her mortal end any longer.

Detail, Embrace of the Angel of Death.

Around it, photographs of an in-process teahouse in Oren's backyard give viewers a peek into his practice, which includes a love for found and repurposed materials—columns found on Craigslist, a slate roof and windows from old churches in New London and Derby, respectively—and the time it takes to get something right.

Oren fell into sculpture accidentally, after failing out of his veterinary science classes at the University of Maryland. Paired with horses and cows during his first semester, “I flunked,” he said matter-of-factly as he walked among hunks of creamy, striated marble last week. Summoned to a meeting at the end of the year, the dean asked him what he was doing with his life.

Oren was drawing every person who walked by the office. The dean declared that he was an art major and sent him on his way.

It led him to Kenneth Campbell, an abstract sculptor who taught him how to use tools of the trade. It was in those classes that Oren laid the foundation of a direct carving practice, in which he studies a hunk of stone until he can imagine the shape that is trying to break out of it and where. While Campbell insisted on abstraction, the young Oren was drawn to figurative works that had withstood the test of time. Michaelangelo Buonarroti’s slaves and prisoners, with their tortuous, torquing forms and rough-hewn bases, grabbed his attention and haven’t ever let go.

Top: Detail of On The Sixth Day, which Oren sculpted in 1974. Bottom: The front of Moshe, a 2011 carving. Oren sourced the marble from a family in Eastern Connecticut who put it on Craigslist.

His themes often come from the Old Testament and from mythology, in a balance of sacred and secular that he has cultivated over five decades of work. Works are also drenched in his own memory and lived experience, including a tableau of childhood fears downstairs that include huge, hairy spiders and snakes devouring his face.

After making his first figurative piece—Oren’s 1974 On The Sixth Day looks as though God’s spindly hand is working the stress ball that will soon become humanity—Campbell stopped talking to him, outraged that he would stray from the teacher’s dogma of abstract-only art. Oren went on to work with the sculptor Ivan Valtchev, whose grant funding happened to bring him to Maryland in the 1970s, and later with New Havener Sy Gresser. As he deepened his practice, he embraced the uncertainty with which a hunk of stone might initially greet him, as he figured out what it was inside.

“There’s nothing cosmic or magical about it,” he said. “It’s like looking at clouds. When things are working the best, my ego just melts away. I’m not worried about what I’m carving. It becomes intuitive.”

Oren’s career has never been limited to sculpture, and the show gives viewers a sense of both his breadth and the dedication with which he approaches his craft. For three decades, he was an editorial cartoonist for the Houston Chronicle, which Hearst bought in 1987. It was during his time in Texas that he met his wife Angela, at a party for the Feast of the Epiphany 35 years ago this month. New Haveners have her to thank for his presence in the city, to which they moved when she got a job at Yale.

Heavenward, which Oren drew for the Houston Chronicle in 1986.

Beside the sanctuary’s doors, his 1986 Chronicle cartoon Heavenward commemorates the explosion of the Challenger Space Shuttle, which killed all seven astronauts on board less than two minutes after liftoff. In the image, a winged astronaut has replaced the canonical image of the expanding, bloated booster plume that swirled into the air as the craft became a cloud of smoke. A rounded slice of earth floats below. Both it and the angel are luminous.

In a curatorial coincidence, the work is installed beside a large plaque commemorating the six million Jews lost during the Holocaust. The objects seem to whisper to each other, reminding viewers of the scale and weight of human loss as time lurches inevitably forward.

The artist left the Chronicle in 2005—he later worked at the New Haven Advocate until a heart attack drove him out of the newspaper business—but the sharp, empathic and sometimes cheeky wit of those pieces comes through the entire show. A larger-than-life tallis hangs above the stairway, drenched in ritual and totally inappropriate for its use at the same time (the piece was originally part of a group exhibition on the Orchard Street Shul from Cynthia Beth Rubin). His 1996 print Depression, installed downstairs, shows a figure pulling his knees to his chest, a shrunken mirror image of himself in his head. It’s an economical, moving portrait of mental illness, striking in how much it conveys while using a childlike design.

Top: Oren's 1973 Terpsichore Crossing the Hudson in Tennessee pink marble. Sculpted a year before his break with Campbell, he described it as "pure abstract." The sculpture in the background is Lot's Wife; prints from his Pareidolia series are above. Bottom: A large, non-functional tallis.

Entropy Warriors is at its strongest when multiple media exist side by side (Oren sources many of his materials from Craigslist, which means that he doesn’t always know what he’ll be working with or on until it's advertised). In the basement, prints from his Pareidolia series hang above his sculptures, encouraging viewers to trust their own interpretations of the works. Named for the phenomenon of seeing patterns or shapes in random objects—Jesus’ face on a pancake may be the most famous example—Oren started the series as he was repairing a lattice, had it covered in paint, and pressed it to thick paper.

Across the splatters of paint, a woman heaves a basket through a rice field. Or maybe it is a bandana-clad protester who got lost on their way to an action. Or a dancer taking their first solo against a black smear of stage and curtain. Oren lets viewers decide for themselves. While the sculptures nearby have descriptive titles, the artist doesn’t get upset when his viewers see something completely different (in Terpsichore Crossing The Hudson, inspired by the patron of poetry and dance, this reporter saw a huge, glittering kidney bean rendered in Tennessee pink marble).

“It’s more fun not to nail it down,” he said.

Top: Oren's childhood fears, the pedestal for which features a cubbyhole with a doll's legs and torso. Bottom: Detail, Oren's 2016 Toad's Place.

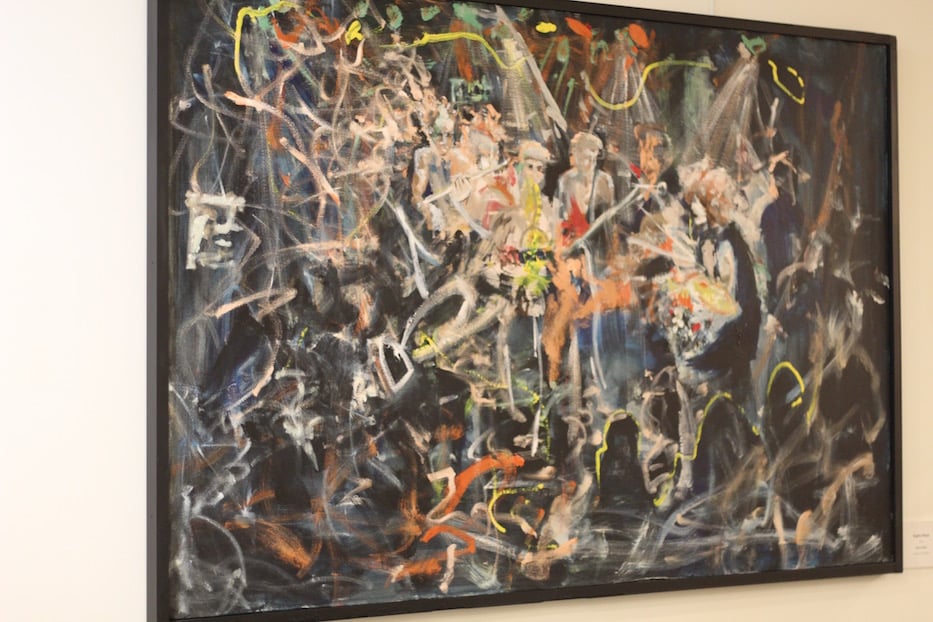

Oren has a sense of down-to-earth practicality that keeps anything from feeling too delicate or precious, and it comes through at every turn (as he said at the end of a recent tour, “I just love making shit.”). In 2016, the Everyone Orchestra posted an ad on Craigslist: would anyone be up for painting its November performance at Toad’s Place in downtown New Haven? Oren took the job, which covered the cost of a ticket, and showed up with a huge canvas. The painting, where colors spring and pulse frenetically against a black background, has now become the beating heart of the show.

In this space of contradictions—BEKI is a holy and contemplative community, but the bones of its 1960 building also feel cold and antiseptic—it fits. Oren doesn’t always know what he’ll find or where he’s going next, and he has long learned to make peace with it. He dips into the jumble of his past and still manages to hold fast to the present. He looks over a shoulder, then forges ahead in the chaos.

Congregation Beth El-Keser Israel is located at 85 Harrison Street in New Haven. More information on the show and Oren’s Feb. 5 talk is available at BEKI’s website.