A felt puppet with swollen eyes and blue lies in bed staring at the ceiling as part of Anatar Marmol-Gagné's exhibit, Sueños. Photo courtesy Arturo Pineda Photos.

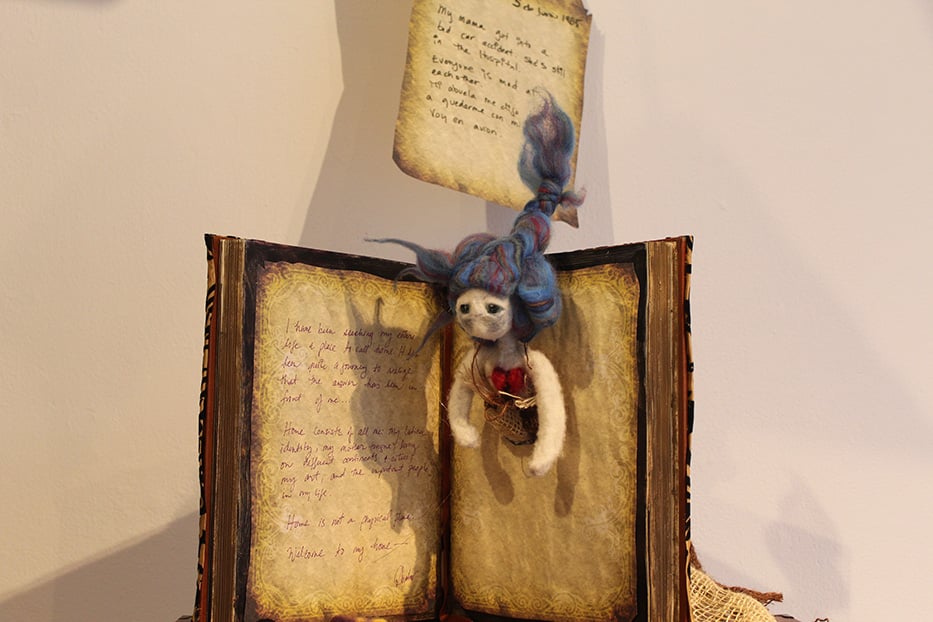

The puppet should be asleep, but she’s wide awake, staring at her journal pages as they float above her bed. The 30-some pages are a whirlwind: they detail a fight with her mother, her father barging into her room one day, and the turmoil of trying to find a constant home. Her eyes are puffy and rosy, almost as if she’s been crying.

The ominous image is a part of Sueños, a solo show from Anatar Marmol-Gagné running at Artspace New Haven through March 20. An in-person performance is scheduled for March 13 at Artspace. Tickets are free but space is limited; attendees must register beforehand.

Marmol-Gagné’s dreamworld is expansive: it even includes a New York skyline and a fairy tale puppet bursting through the pages of a book. But her story is as much about nightmares as it is about dreams. In her own words, the installation is about searching for a sense of home that escaped her throughout her childhood and young adult life.

“Every time I felt I was getting comfortable there was another move or shift,” she said. “I wish I could just hang out with my cousins.”

The idea for the installation, which is heavily autobiographical, first came to her in 2013. She didn’t start seriously working on it until 2018, after workshopping it at the Dramatic Question Theatre in New York. Even now, she considers the installations to be her most recent work-in-progress.

Grounding the exhibition are pivotal moments in her life, including her parents’ bitter divorce when she was just two-and-a-half years old or her mother’s car accident in 1985. What followed was the familiar and disorienting process of living with her mother in Caracas, Venezuela for some years and then moving to her father’s home in New York and repeating the journey.

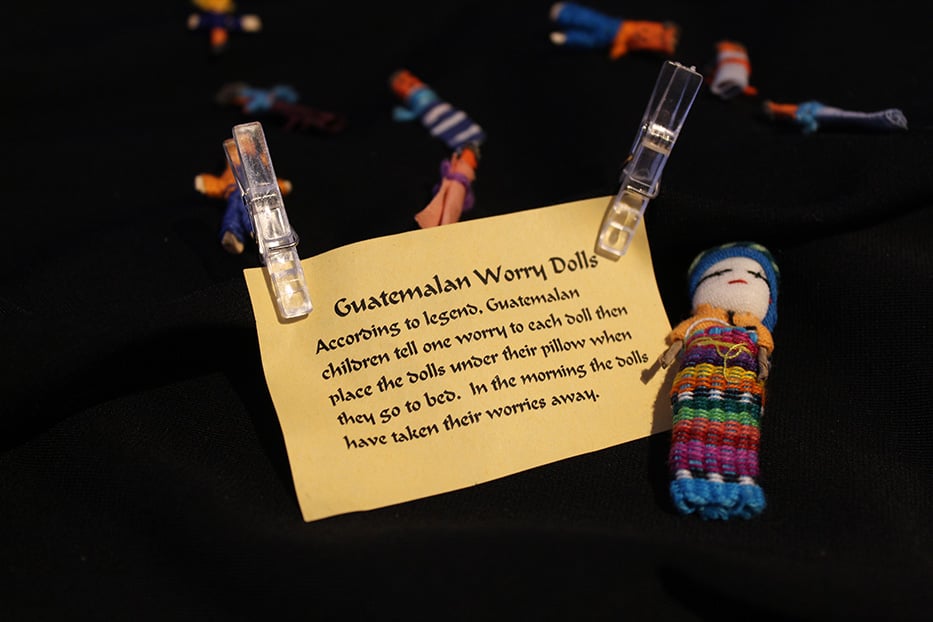

She remembers the fights, confiding in her maternal grandmother, and turning to her Guatemalan worry dolls. The legend goes that if a child whispers a worry to a doll before going to sleep and places it under their pillow then the worry will be gone by the morning. As a child, she was worried that she had too many worries and would wear out the dolls.

“I would put them in a certain order to make sure they were charged enough before using that doll again,” she said in an interview Friday.

Text Reads: Guatemalan Worry Dolls. According to legend, Guatemalan children tell one worry to each doll then place the dolls under their pillows when they go to bed. In the morning, the dolls have they taken their worries away.

Text Reads: Guatemalan Worry Dolls. According to legend, Guatemalan children tell one worry to each doll then place the dolls under their pillows when they go to bed. In the morning, the dolls have they taken their worries away.

The dolls serve as a foil to the freeing realization she had years later: she had been carrying emotions and worries for years that were never hers to begin with. In the live performance, the army of dolls rise up to fight a nightmare monster.

After her mother was in a car accident, her father took her to live with him and her new stepmother. Marmol-Gagné was just eight years old at the time. For the next seven years, she only saw her mother in court. Suddenly, the mother who she knew so well became a stranger.

It was not until her 15th birthday, when her mother visited, that she learned that her mother had never given her father permission to take her.

“It took some time to repair things that had transpired in those years,” she said. “I’ve forgiven my parents. I love them dearly now.”

A year later when she was 16, she started over and moved back to Caracas to finish high school there. The visit had been intended to be a short stay but extended into six years.

The trunk in the corner of the room is a direct nod to the traveling she did between Caracas, Venezuela and New York. The shadows puppets projected out onto a warm red screen represent the missing memories lost with each move. The outlines remain, but there is nothing inside.

Having done schooling in English and Spanish, she was drawn to translation and interpretation partially because it met her interests and paid the bills. She described her time in Venezuela as a “constant upstream to find stability” which came to a head with Hugo Chávez’s election in 1999.

She and her mother were aligned with the anti-Chavistas, opposing the nepotism present in their community. At odds with the political climate, she left to pursue an English and Creative Writing Degree at Hunter College in New York City. She returned to school in 2013 to earn a Masters of Fine Arts in Puppet Arts from the University of Connecticut.

The narrator puppet pops out of the fairytale book welcoming guests to the exhibition.

The narrator puppet pops out of the fairytale book welcoming guests to the exhibition.

The intimacy of the show comes through most strongly in the journal entries that hang above the bed. Each of them is a faithful replica of her own journal entries, even the doodles. In the “pandemic blessing” with spare time on her hands, she sat down and combed through more than 30 years worth of journals.

“I wanted to understand the trajectory to some extent,” she said. “I feel like there are these big holes in my childhood … growing up having a solid base and being anchored and suddenly not having that.”

The fairy tale-like puppet at the front of the exhibit is the narrator, who just like Marmol-Gagné, has finally punched through the storybook tale. She has punched through years of daydreams, nightmares, and fantasy to bare all in this installation to tell her story of home.