Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | The Hill | History | Arts & Anti-racism

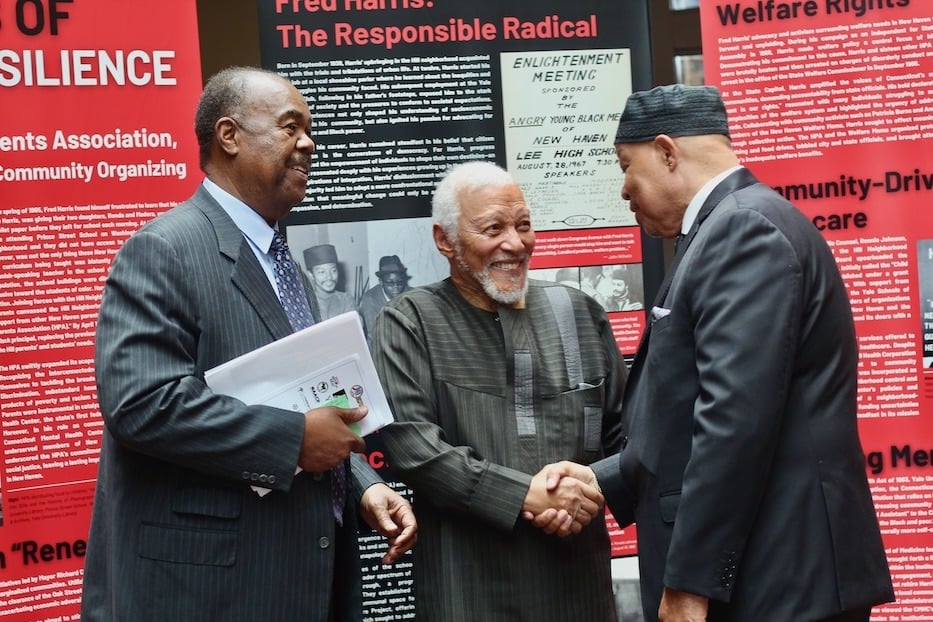

Dr. Pamela Monk Kelley, Fred Harris, Sophie Edelstein, Lorena Mitchell and Myles Riley. Lucy Gellman Photos.

When Fred Harris pushed for better classroom conditions, functioning bathrooms, and a Black principal at Prince Street School, he didn’t know he was starting a movement. Six decades later, he’s finally getting his due.

Harris, who founded the Hill Parents Association in 1965, received his flowers Friday afternoon at City Hall, during a two-hour recognition ceremony and exhibition unveiling in the building’s airy atrium. As speaker after speaker took the podium, an image emerged of a fierce and dedicated community activist, whose work became a template for organizing across racial and socioeconomic lines in New Haven and across the country.

It doubled as a kickoff to a celebratory Hill-centric weekend, including a formal presentation Friday night at the New Haven Museum and Hill Neighborhood Festival in Trowbridge Square Park Saturday afternoon. After its time at City Hall, the exhibition will live at the Wilson Branch of the New Haven Free Public Library.

“The fight is not over, and you have to take your place,” said Harris, who now lives in Detroit and runs New Risen Christ Ministries International. “As long as you’re breathing, you got to speak, you got to get together, you got to meet, you got to organize against the giant that is destroying your community.”

“Aren’t you tired of being pushed around?” he added to appreciative murmurs that made City Hall feel more like church. “You can stop ‘em if you unify.”

The recognition is largely thanks to Sophie Edelstein, a recent graduate of the Yale School of Public Health who grew up in New Haven, and to lifelong Hill resident and neighborhood booster Dr. Pamela Monk Kelley. During her time at the School of Public Health, Edelstein dedicated her thesis research to the work of Black organizers on community mental health efforts in New Haven. She learned about Harris through U-ACT's Billy Bromage, who connected her to Kelley.

Friday, she and others explained that Harris’ footprint in New Haven is a record of speaking truth to power. In 1965, his organizing work began unexpectedly at home on Carlisle Street, when he saw his daughters Rhonda and Madera headed to school with extra toilet paper in their hands. When he asked his then-wife, the late Rose Harris, he learned that they did not have toilet paper in the school’s bathrooms.

Harris and New Haven Poet Laureate Sharmont Influence Little.

It was one of several sub-standard conditions at the school. At the time, Prince Street School had very few Black educators (that’s still true across the district, where New Haven’s teachers do not reflect the student body), no Spanish-speaking teachers and a white principal who was allegedly an alcoholic. The building was falling apart, in a pattern of neglect for Black and Latino students that may feel jarringly familiar decades later.

Harris, with his wife and several other parents from the neighborhood, didn’t let it rest. Working with members of the Hill Neighborhood Union (HNU), he and fellow parents created a list of demands for the school, from stocked and functioning classrooms to integrated textbooks to a new Black principal. Parts of it, including the ask for a new principal, were fulfilled within a year.

It was just one step in what became a transformative neighborhood campaign. In 1966, Harris announced a bid for public office, running to represent New Haven in the Connecticut General Assembly. Less than a year later, members of the HPA founded and published a community newspaper, “Ram and Sheep,” that blasted Dick Lee for a vision of “Urban Renewal” that had torn the city apart.

Retired Probate Judge Clifton Graves, who emceed the event.

They advocated for the neighborhood’s growing Puerto Rican population, including its Spanish-speaking kids. They made the case for “Freedom Schools,” educational hubs where Black students could learn more than what New Haven’s classrooms were giving them. They understood acutely that racism and poverty were co-dependant weapons of white supremacy, meant to pit people of color against each other, and fought the problem at the root.

“He [Harris] knew he couldn’t change the system from the outside, so he changed it from the inside,” Edelstein said.

When Harris was arrested on narcotics charges in 1967, hundreds rallied to clear his name. They organized again two years later, when Yale voted not to rehire him as a special assistant to the director at the Connecticut Mental Health Center (CMHC). In their midst, Harris kept organizing—for jobs, for education, for Yale to pay its fair share. With HPA members Willie Counsel, Ronnie Johnson and his wife Rose, he also helped launch what would become the Cornell Scott Hill Health Center. It made history as the first Federally Qualified Health Center in the city.

By the 1970s, the HPA was part of a citywide Black Coalition with the NAACP and Freedom Now Party, with enough momentum to push Yale President Kingman Brewster and members of university administration to make a larger financial commitment to the city’s Black community. Despite disagreements with CMHC administration in the late 1960s, he was instrumental in the founding of the CMHC’s Hispanic Clinic in the early 1970s. He remained one of Lee’s most outspoken critics, enraged as he watched the long-term effects of slum clearance render parts of his city unrecognizable.

Connecticut NAACP President Scot X. Esdaile.

And then, noted Connecticut NAACP President Scot X. Esdaile, he was “run out of town.” In that sense, Friday marked a full-circle moment, with a welcome from not just activists and organizers, but also elected officials who now recognize Harris’ importance in the city. Or as Mayor Justin Elicker said, “We don’t thank our elders enough for what they taught us … Mr. Harris is an example for so many of us.”

Friday, multiple speakers pointed to that legacy in a lineup that included spoken word, awards, a mayoral proclamation, and laughter-flecked conversation that lasted well after the ceremony had ended. In addition to a number of city officials and Hill residents, collaborators included the International Festival of Arts & Ideas, the Hill North Management Team, and representatives of Cornell Scott Hill Health Center.

Presenting Harris with the NAACP’s Humanitarian Award, Esdaile praised Harris for “belling the cat”—for bringing attention to the way white supremacy was and is wreaking havoc on the Hill neighborhood and on New Haven. He pointed to the anecdote from Dr. Benjamin Hooks, who led the NAACP from the 1970s to the 1990s, about a small army of mice debating who among them would place a bell on the cat who was terrorizing them. “That’s an individual like Fred Harris,” he said.

“So much has not changed,” he continued. “Our people have always been belling the cat … [and] when we fight, we win. When we organize, we win.”

Sha McAllister, associate director of education and community impact with the International Festival of Arts & Ideas. McAllister explained that Kelley suggested honoring Harris at the neighborhood festival, and the rest was history.

Educator Marcella Monk Flake, a Connecticut Arts Hero who grew up on Cedar Street in the 1950s and 1960s, called Harris “a rockstar for me.” As a child, Flake had “bought into the lie” that she was inferior because she was Black. Then she saw Harris walking through the neighborhood, his back straight and head held high.

It reminded her of her father, Conley Monk, who taught her and her eight siblings to believe in themselves. When riots shook the neighborhood and brought the National Guard into the Hill in 1967, sending tear gas into a window of her home, it also gave her a sense that something was deeply unjust about what was happening.

“We were little kids and we were watching you,” she said to Harris, her eyes scanning the room until she met his. “We knew there was something different. You were a catalyst, Mr. Harris. You ignited something in our community.”

“He was bigger than life,” she added in a conversation after the formal presentation. “He was larger than life. When he walked in tonight, the tears just came streaming down my face.”

It lit a spark in her, and many of her eight siblings, that never went out. Pamela became a teacher and the de facto family historian. Olivia, who siblings called “Chris,” grew out an Afro. After the Monk’s pastor expressed concern that she would become a Black Panther, Monk Flake’s mother—also Olivia—sewed purple dashikis for several of the girls to wear to Sunday worship.

“It’s been a joy connecting with him and his family,” Kelley said. “Today, we celebrate him.”

When it was time for him to speak, Harris kept it short, urging attendees to identify and fight systems of power in their own communities. At 85, he still floated across the floor, haloed in sunlight as he took the podium.

“It’s very humbling to me, all the things that were said,” he said. “I don’t feel that was me. I just did what I had to do.”

He warned that without continued action, New Haven will become a college town that disproportionately serves white people. He pointed to the power of coalition building, which in New Haven is a multiracial, multigenerational, and cross-cultural effort. And just as he did in the 1960s, he called for greater accountability from Yale University, from job security to its financial support of Black and Latino neighborhoods.

"America is a lie," he said, noting that the Founding Fathers do not represent the majority of the country. "We need to make it what it's supposed to be."

In separate interviews, both Edelstein and Kelley said that the honor has been very much a team effort, with collaborators that range from U-ACT to the Hill North Management Team to the New Haven Free Public Library among others. At Yale, Edelstein worked closely with Professor Marco Ramos, as well as members of the university’s public history initiatives and evolving Critical Histories Lab.

She and Kelley also brought in city partners, including Mental Health Coordinator Lorena Mitchell and Cultural Affairs Administrator Myles Riley. After years of work, Edelstein said she’s thrilled that the project is now accessible to city residents.

This summer, city officials also plan to rename South Frontage Road and Park Street as Fred Harris Way.

For Esdaile, it was a long time coming. "This is family, y'all," he said.

To listen to spoken word that New Haven Poet Laureate presented at the ceremony, click on the video above.