Black History Month | ConnCAT | Drama | Arts & Culture | Theater | Quinnipiac University | Arts & Anti-racism

Black (Rodney Moore) and Gold (Sharmont Little). Lucy Gellman Photos.

Black (Rodney Moore) is hurt, grimacing as he holds his right calf in his arms. He whimpers, and a playground materializes around him. Even without props, it’s enough to see the bars or swing set from which he has inevitably tumbled. In front of him, his father’s face collapses into rage. Words float over the stage, in a sing-song rhythm that is rotten at its core: Boys don’t cry! Boys don’t cry! Boys lie about what they feel inside!

That no-nonsense, often biting verse flows through Death By 1,000 Cuts: A Requiem for Black And Brown Men, a new work from playwright Steve Driffin and a creative team bringing it to life at Quinnipiac University this month. On Feb. 11 and 12, the show will have its first official staged reading at Quinnipiac’s Clarice L. Buckman Theater, part of an eight-year process that has included men’s support and bereavement groups, dozens of one-on-one interviews, fragments of poetry, and hundreds of edits.

The show runs the evening of Feb. 11 and the afternoon of Feb. 12, during a week of screenings and performances for Black History Month. Tickets and more information are available here.

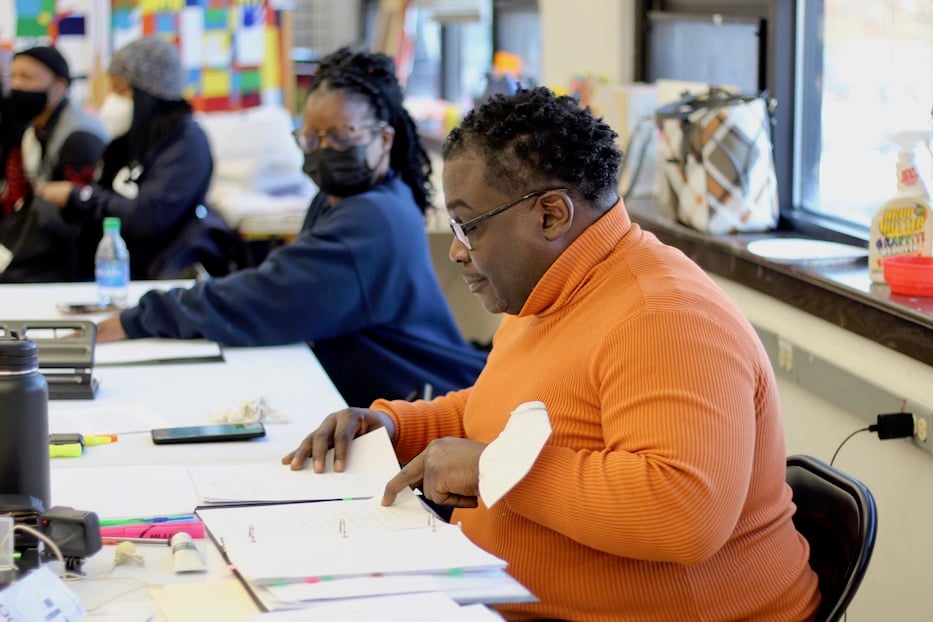

Playwright Steve Driffin. “This play is a mirror and a window,” he said.

“This play is a mirror and a window,” Driffin said at a rehearsal Sunday afternoon at the Connecticut Center for Arts & Technology (ConnCAT), where he is the director of youth programs and co-director of operations. “It’s a mirror for us”—he looked around at the fellow Black men in the room—”and it’s a window for those who may be coming from different experiences. And the layers … it’s layers and layers.”

The work began eight years ago, when Driffin walked into a 2013 meeting of Fathers Cry Too and took a seat. The group, a peer support network for fathers who have lost their children to gun violence, welcomed Driffin as a visitor. In his hands, he held a small journal, its pages still crisp and blank. When he opened it and dated the entry—Oc. 22, he remembers to this day—he didn’t know that some of the men in the room would become his confidants, his brothers in spirit, and his greatest inspirations.

“It was the most incredible group of men, the strongest group of men I have ever, ever been around,” he recalled in an interview on WNHH Community Radio last year. He became particularly close with founder Thomas Daniels, Sr., who lost his son, Thomas Daniels Jr., to gun violence in 2009, and to Sean Reeves, Sr., whose 16-year-old son, Sean Reeves Jr., was shot and killed in August 2011. He was moved by the strength that these men had found in their ability to be vulnerable—with and sometimes for each other.

Gold (Sharmont Little). He said that he sees the work as busting through centuries of harmful stereotypes about Black men.

It was as though he had fiddled with a knob, and a huge, heavy door had swung open. From Fathers Cry Too, Driffin started to probe deeper questions that he had around Black masculinity. He talked to Black Obsidian Men’s Group founder Eric Rey about trauma and healing. He made room for discussions that ended in weeping. He connected with fatherhood coach Bruce Trammell. He kept writing and rewriting, sometimes juggling multiple projects as he built on his research. One journal became several. He kept transcripts and recordings.

Then Covid-19 hit New Haven.

By summer 2020, Driffin had six and a half years of material. Around him, the pandemic had put physical gathering largely on hold. Every time he flipped on the television, the radio, or social media, he risked being inundated by the spectacle of Black death. He could feel something shifting in him, trying to make its way out.

“We saw the murder of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor,” he said. “I was angry. I was angry and I wanted to retaliate. And that’s when it began to write itself.”

As he wrote the play, Death By 1,000 Cuts took several forms. In one, it was a conventional script, with four Black men meeting up at the bus stop and starting to talk. Then it was snippets of his own poetry, trying to fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. Then he landed on a script with rhyming and free verse, riffs on childhood lullabies, song fragments and a lilting lyrical swerve. He folded in music from Jimi Hendrix, M.A.Z.E., The Temptations, and J. Cozier. It stuck.

The weight and necessity of being vulnerable—and the price, fear, and trauma surrounding that vulnerability—remained the wildly beating heartbeat of the show. That never changed.

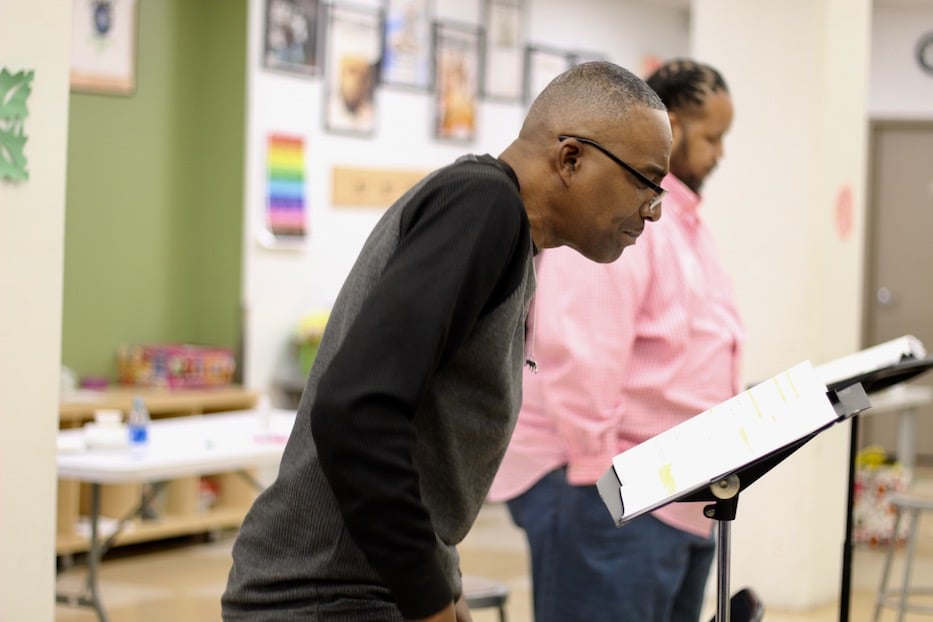

Green (Jason Hall) at Sunday's rehearsal.

Cast members for this performance include Red (Stephen King), Gold (Sharmont Little), Black (Rodney Moore), and Green (Jason Hall)—the four colors that together build the Pan-African flag. On Sunday, three of them buzzed around a second-floor classroom at ConnCAT, repurposed as a performance space. Driffin handed out new copies of two pages he had rewritten between rehearsals. “I can’t promise that I won’t rewrite this again,” he said with a laugh as he handed a copy to Hall.

Moments later, the team was all business. Producer Mercedes Sherman sat beside Driffin, taking notes as he filled in for King. Photographer J.E. Wolf picked up her camera and scanned the room, finding the best angles. The opening of Jimi Hendrix’ “Star-Spangled Banner” ripped through the air, and actors raised their fists in unison. As it faded, they stepped into Driffin’s world—which is also their world—and let the work take over.

While Death By 1,000 Cuts runs only an hour, it is both tight and surprisingly spacious, with a sense of movement that keeps both the actors and the audience on its toes. Rehearsing Sunday, characters jumped nimbly from the school-to-prison pipeline to the history of policing to the sanctity of Black love (“that pickled pigs feet and hot sauce kind of love!” may be one of the play’s most beautiful lines). They dove head first into the trauma of abandonment and isolation, pulling back to explore the ecstasy of fatherhood and fear that it will be cut short by violence.

Producer Mercedes Sherman, one of multiple crew members on the show. Driffin also shouted out photographer J.E. Wolf and producers Anita Battle, Karina Medved-Wu and Cassie Volcy for their help.

In between, they pulled the work into the present, with nods to the death of Kalief Browder, controversy that has exploded around critical race theory, decades-long attempts at voter suppression, and the hollowness of some diversity, equity, and inclusion work. It’s a sharp and clear-eyed look into structural racism, white supremacy and a historic lack of access (to generational wealth, to professional development, to mental health resources) that tugs a listener’s ears.

“Diversity and inclusion/It’s just an illusion!” Black proclaims to the audience at one point, and the line sizzles with its timeliness.

“They keep changing the rules of the game/Just to keep their seclusion,” Gold responds. In it, audience members can see new legislation around voting, concentrated wealth, and a criminal justice system that doesn't feel just at all.

What makes the work feel intimate, sometimes unflinchingly so, are the anecdotes that come directly from interviews Driffin has done and from the playwright's own life. There is the white elementary school teacher who assumes that his Black, male students are fatherless and live in the projects, but is so offended by allegations of his own racism that he kicks those same students out of class. In the audience, we know that he is launching a disciplinary timeline that will hang over them for decades.

Moore, whose character is subject to intense homophobia at one point in the script.

Or the little boy who gets injured on the playground, and so disappoints his father by crying that he becomes an easy target for bullying in his neighborhood. When he later becomes violent himself, it’s not a surprise—hurt people hurt people back. He’s been hardened by a barrage of slurs that are violently anti-gay, anti-Black, and anti-woman. Throughout it all, the actors have chemistry with each other, giving the show a presence that feels bigger than just a staged reading.

Driffin, who was born in New Haven and raised in Brooklyn, has an eye for how to collapse timelines in on each other, and he often injects them with just enough poetry to remind viewers that they are still in a theater space (“abandonment became my residence,” spoken by Red, is one of the show’s most memorable lines). Suddenly, this commentary on race, racism, and masculinity is a container in which people’s real-life fears and memories live.

The playwright, who can flow from the New Testament to Miles Davis in the same paragraph, is careful to strike a balance that dives into generational trauma and also upholds the possibility of joy. In doing so, he crafts a play that is also a calling in. Audiences don’t get his vision of a better world, exactly. They get something much more powerful: the tools to help create one.

His characters are not shy in urging people in the audience to seek professional help. They put out direct calls to men in the audience, and to fathers in particular, to reach out if they need a support system. They apologize to Black women, using a call and response of “My Sister!” that competes with a thrumming whisper of “Be a man/Be a man/Be a man.”

Jason Hall.

Nowhere, perhaps, is that more evident than in the work’s final stretch, as characters weave in and out of a rap about “the shuns”—the anxiety and clinical depression with which they each live as Black men in America. After years of hearing men speak candidly about their own struggles with mental health, Driffin has stitched it aurally into the script in a way that will stay with listeners long after the lights have come down.

During a break between back-to-back run-throughs, Moore, Little and Hall all said that they are all grateful to be part of the show. Little pointed to the role that it plays in “debunking many of the myths” that have long existed around Black masculinity and fatherhood. Moore, who works as the fatherhood coordinator with New Haven Healthy Start (NHHS), said that the work resonates deeply with him, because it is filled with some of the same deep concerns he hears every day from the men he works with.

“This helps me see from their point of view,” he said. “This piece is the epitome of what we are dealing with as Black men."

Death By 1,000 Cuts, A Requiem for Black And Brown Men runs Feb. 11 at 7 p.m. and 12 at 2 p.m. at Quinnipiac University. Tickets and more information are available here. To listen to an earlier interview on WNHH-LP with Steve Driffin, Sean Reeves, Sr. and Thomas Daniels, Sr., click on the audio above.