Culture & Community | Downtown | East Rock | Painting | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

Constance LaPalombara painting in Tuscany. Photo courtesy Susan LaPalombara. The third photo in this article is also courtesy Susan LaPalombara.

The first thing you notice is the light. The pears are mere suggestions of themselves, with hints of blue and green that pool at the ends and edges. They fall into each other, luminous and impossibly airy. Shadows bloom beneath them in gray and blue. Even the paper seems to glow with a warm crispness. At the lower right, a signature from Constance LaPalombara graces the page.

Friends, family, and members of New Haven’s arts community are mourning LaPalombara this month, as news of her death makes its way across the city and into the wider world. A talented painter, sharp-tongued conversationalist, fashion icon, voracious reader, de facto teacher and generous friend, LaPalombara passed away Feb. 14 in Hamden at the age of 87. At the time, she was living at the Whitney Center and still painting at a studio in the MarlinWorks Building on Willow Street.

Her husband of 51 years, Yale political scientist and professor emeritus Joseph LaPalombara, called it “a profound loss” to the family, to the community, and to the art world. She was one of the founding members of Kehler Liddell Gallery, which still sits at 873 Whalley Ave. in Westville, and has work in collections across the globe.

“I am who I am and what I am largely because of her,” Joseph said in a phone call last Wednesday. “She taught me an immense amount. We were able to look at art in places like Berlin, Rome, Paris, Washington D.C., London. She managed to teach me to look at color and to look at light, and to look at brushstrokes. In short, I was one of her most ardent admirers and students.”

“She never seemed old,” said the artist Amy Weiskopf, who met LaPalombara in graduate school and remained friends with her for the next five decades. “The things she cared about, she had an enthusiasm for them that never ever ended. She had such a drive.”

In her lifetime, she left an artistic footprint that spanned New Haven, Maine, Italy, Philadelphia and briefly London. A web of friends is already feeling her absence at their gallery openings, plein-air painting sessions, critique groups and art brunches. In nearly a dozen interviews, they painted her as both a gifted artist and an elegant woman who flowed through the world, as curious and witty as she was neat as a pin.

A LaPalombara watercolor of pears now in a private collection. Image courtesy of the owner.

Born in Long Island in 1935, LaPalombara did not formally come to art until she was in her 40s, but grew up as the child of an amateur painter. While her mother never pursued art, “she was talented,” Weiskopf remembered, and the young artist grew up surrounded by oil-on-canvas works that she later held dear. To this day, Joseph LaPalombara remembered, there is an oil of his wife as a young girl in their own collection. It remains one of his most treasured possessions.

Painting, initially, did not seem to be her first calling. After her studies in political science at Manhattanville College, LaPalombara worked for the Central Intelligence Agency, although what she did, and for exactly how long she worked, no one interviewed was sure (she told architect Craig Newick said she told him she was a secretary; the CIA did not reply to a written request for comment). Even Joseph, with whom she shared decades of stories, said that she remained tight-lipped when the subject of the CIA came up. “We did not discuss that often,” he said.

By the late 1960s, she was working under Dr. Alex Dallin at Columbia University, where he ran the school’s Russian Institute. It was through that work that she met Joseph, who was then involved with the Social Science Research Council of New York, and already on the faculty at Yale University. He remembered their first encounter, at the Harriman Institute just blocks from the Hudson River. The two were married just years later, in 1971.

She and Joseph would spend the next five decades between New Haven, Maine, and Italy, with stops in London, Greece, Berlin, Paris, and Ireland along the way. In the 1970s, LaPalombara began to paint seriously—first on her honeymoon, and later in New Haven. At the time, she and Joseph rented an apartment by the university, then found a house in New Haven, where they lived for the next 50 years.

“She became slowly interested in painting,” Joseph remembered. As her interest bloomed, her favorites included the Italian painter and printmaker Giorgio Morandi, as well as Balthus, the late William Bailey, and Antonio López García. In New Haven, she was able to study with faculty at the Yale School of Art, including Bailey and Andrew Forge.

In 1980, LaPalombara enrolled in the Tyler School of Art at Temple University, with no intention of ever studying on site in Philadelphia, according to Weiskopf. That year, Joseph had been tapped as the cultural attaché to the U.S. Embassy in Rome, and LaPalombara planned to study in their exchange program for the entirety of the degree. Instead, she came back to Philadelphia after a year.

She took immediately to Weiskopf, and Weiskopf to her, despite the 21 years between them. As students in art school, “Constance and I felt like the other person was the only sane one around,” she remembered in a phone call. While the two were both dedicated to their craft, “we both also loved to have a very good time.” After working for hours, consumed by their art, they would go out on the town.

The two had a bond that lasted for another four decades. When Weiskopf decided to study in Rome through the university’s exchange program, both Constance and Joseph LaPalombara helped her find an apartment, and later cheered her on when she moved to Rome permanently for nine years. In Italy, she could see how much her friend loved the wide, open countryside, and fell in love with it too.

“They opened doors for me that were just so magic and rich,” Weiskopf said. She remembered a shopping trip in Italy that the two took together, during which LaPalombara helped her find “the best vase” to paint—which she did, over and over again. That was just her friend, with a sense of delicate and impeccable taste that she was always willing to share. When in 2013 Weiskopf moved to New York after years in Rome and New Orleans, LaPalombara visited her in the city.

“She was a role model for all of us,” she said. Weiskopf remembered feeling surprised when she first received the news that her friend had died. “She was a peer. She was so youthful, we never saw her as being older.”

“None Better, Damn Few Equal”

If Italy had one part of LaPalombara’s heart, Maine had another. In the summers, she and Joseph spent months in Bar Harbor, in what became a LaPalombara family tradition. Her stepdaughter Susan LaPalombara, who described her as “a second mom to me,” remembered years spent there, watching LaPalombara devour books as she laid back, and read on the bench of a fishing boat.

If Italy had one part of LaPalombara’s heart, Maine had another. In the summers, she and Joseph spent months in Bar Harbor, in what became a LaPalombara family tradition. Her stepdaughter Susan LaPalombara, who described her as “a second mom to me,” remembered years spent there, watching LaPalombara devour books as she laid back, and read on the bench of a fishing boat.

It was there, as well as on trips to London and Italy, that the two became extremely close. For one thing, Susan said, they could laugh together, and often did. There was also a kind of grace and no-nonsense attitude that extended to nearly everything she did. LaPalombara would never leave a book unfinished, even if she hated it. She hiked, kayaked, and played tennis avidly. She also took the time to paint, looking out onto the surrounding cove as she lifted brush to canvas.

In fact, those summers were also some of the only times Susan saw LaPalombara painting, out on the house’s open deck. It was part of her love for light and open space, so clear in the hundreds of human-devoid canvases she did of New Haven, from studios on Orange Street to the MarlinWorks Building.

Muffy Pendergast, assistant director at Kehler Liddell, remembered visiting LaPalombara in Bar Harbor and understanding the peace she felt in nature.

“It was just this big open deck to the water in the distance,” she said in a phone call last Thursday. “It was just airy and just … it just felt very uncomplicated. I think she really resonated with nature.”

Maine was also where many of the family’s memories were made. Alicia LaPalombara, the eldest of four granddaughters, remembered visiting during the summers as she grew into adulthood. Even in her youth, Alicia loved those trips, knowing that her grandmother would listen and take seriously whatever her grandchildren had to say. She looked forward to both summers and Christmas, which she would spend with her grandparents in New Haven.

Years later, she got to know her grandmother’s sharp and dry wit, which ranged from book reviews (“She wouldn’t pull punches!” she said) to meticulously spelled-out games of Boggle, played among sharp cocktails and sharper laughter. She recalled sitting around the dinner table on a recent trip, coming up with a potential family motto with her sisters and husband. It had the group giggling at suggestions like “It’s just my opinion but it’s right,” Alicia remembered.

LaPalombara listened, remaining very quiet until the end of the conversation. Then she piped up. She’d actually had a family motto, she said. It fit her immediately. “None better, damn few equal.”

“Since she passed away, we’ve raised a glass to her” with that motto, Alicia remembered in a phone call at the end of February.

“She was funny and witty and just so worldly,” she later added. In her home, she said, she now holds dear some of her grandmother’s art and furniture. “It’s a lovely reminder of her. I feel like there’s something of hers in every room of my house, so I feel surrounded by her presence.”

That romanticism followed LaPalombara far beyond Maine, and to trips to the U.K. and Europe (and less far afield, often to the Metropolitan Opera) that became defining experiences for the family. When Susan was 15, she remembered spending a year with Constance and Joseph in London, spending much of her time in museums and at the National Theatre.

It instilled in her a deep reverence for the arts that later followed her to Yale, where she studied philosophy, and to a graduate degree in theater at Arizona State University. “My love of art and my understanding of art is all because of her,” she said.

She remembered a trip to Ireland during her spring break, when they left the flurry of London city life for the quiet of Kilkenny. LaPalombara found a thatched cottage, heated only with peat, and insisted that they read Shakespeare around the fire. There were hundreds of moments like that, across countries and countrysides that took them from England to Italy to Connecticut and back again.

“I wish I’d gotten to see her paint more,” Susan said close to the end of a phone call last week. “She’s a spectacular painter. We’re all so lucky that we have her art to remember her by. It’s her eyes, right? It’s what she put to paper, put to canvas. And what she painted is places that we love, and that are home to us.”

“Once You Were In Her Orbit, You Were A Friend For Life”

Constance and Joseph LaPalombara in Frank Bruckmann's Breaking Bread series. Image courtesy of the artist.

In New Haven, she became a champion of many of the city’s artists and institutions, including Artspace New Haven and a critique group that grew into a tight-knit breakfast club. Eileen Eder, who first met LaPalombara in a painting class at Creative Arts Workshop (CAW), remembered her as at once chic and fearless, documenting the city as it changed rapidly before their eyes.

“We would go to all kinds of locations across New Haven and paint together, and it made it special,” she recalled in a recent phone call. In the early 2000s, the two were able to get into the Chapel Square Mall, by then a shell of its former self. They made it to the top floor, where the huge, still-intact windows looked out over Chapel Street and the New Haven Green. Within years, it had disappeared from the city’s landscape.

“It was amazing how many times we painted something and within a couple years it would be torn down or gone,” Eder said, remembering cityscapes of the old Q Bridge and buildings that have since given way to new apartments. “We started to laugh that we were the kiss of death for New Haven.”

With artists Dean Fisher and Frank Bruckmann, she and Eder also became members of an informal critique group that for years met regularly to talk about each other’s artwork. Fisher, who is a painter and amateur woodworker, remembered her as a fierce friend who never minced her words, and had a sense for light, air, scale and color in her own work that felt poetic.

“You had to prepare yourself because she would always speak her mind,” he said with a laugh in a recent phone call. When she didn’t care for a painting—which was often—she would joke that it was destined for Fisher’s woodshed. “If she didn’t like something she would say it, and if you liked it, she would say ‘I’m very happy for you.’”

“She didn’t immediately accept you into her orbit,” he added. “It was a gradual process. But once you were in her orbit, you were a friend for life. The more you knew her, the more she would open up and be very expressive.”

Courtesy of a Private Collection.

The four, sometimes with their spouses, became a breakfast group, meeting for years at The Pantry on State Street and Bella’s in Westville. Bruckmann, who later visited her in Maine with his wife Muffy Pendergast, remembered her as “such a spectacular person,” with a precision and grace that went far beyond her paintings.

He later painted her with Joseph in his Breaking Bread series, a collection of works painted over dinner with friends. In the work, she is regal even in a striped turtleneck and slouchy black sweater, her left hand reaching for a glass of red wine. She looks up at something, and the viewer immediately wants to follow her gaze.

Around town, she was known as much for her sharp sense of style as she was for her canvases, orderly as Morandi’s and infused with light.

Artist Linda Lindroth remembered seeing her in the city before she ever knew who she was. At gallery openings and on the street, she always knew to look out for the petite artist with the tidy shock of white hair, all black clothing, and a tiny leather jacket. She remembered thinking that was how she wanted to look when she got older.

Ten years ago, the two became floor mates in the MarlinWorks Building, where they both had their studios. While the floor remained relatively quiet during work hours, Lindroth “would stick out my head and say, ‘Is anybody here?’” and sometimes, it was LaPalombara who would respond. The two often spoke about the city’s art scene, or a shared love for style that filtered into the neatness of their work.

“We were close in our thoughts about New Haven arts,” Lindroth said. “We shared a very similar viewpoint about events that happened in the city. We would discuss the arts. She was a very, very responsive artist.”

It was through those discussions that Lindroth learned of LaPalombara’s fierce love of Artspace, and her years-long support of City-Wide Open Studios. Each year she participated, Lindroth remembered, her friends would race toward her studio, often slipping past the other three artists on the floor. It would have been infuriating, perhaps, if it were not so sweet.

Architect Craig Newick, who moved onto the floor in 2001 (and is married to Lindroth), also knew of the artist before he actually knew her. After moving to the city in 1984, “I noticed Constance everywhere,” recalled Newick. For 10 years, he worked across the hall from LaPalombara, checking in with her every so often. He remembered how she would come into his studio, pick up some of the materials he was working on, and start asking what they would become. It always led to a discussion on the latest thing he was working on.

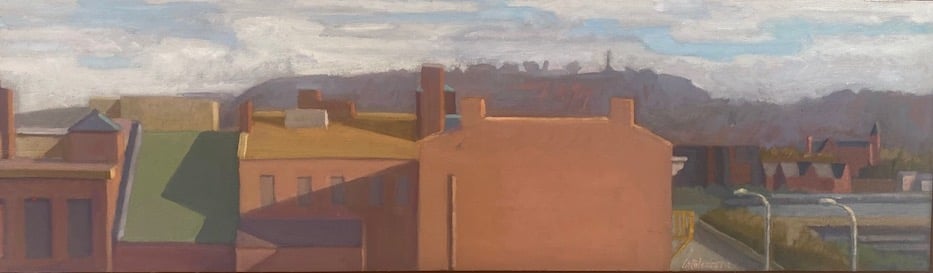

Both friends and family said they are grateful that she will live on through her work. During her lifetime, LaPalombara painted hundreds of New Haven cityscapes, tableaus that are instantly recognizable for those who live (or have lived) in the city. Many are of East Rock and downtown, revealing new ways to look at Orange Street, the Mill River, Long Wharf and the Long Island Sound.

In her work Which Way, for instance, she has rendered a bird’s-eye view of Elm and Orange Streets, looking over what is now Lucretia’s Corner. No cars blow through the space; it’s so peaceful that it would seem eerie, if not for a heaven-sent light. It’s the intersection quite unlike anyone has ever seen it, high enough above the awnings that they seem to pulse with color.

In another, which now sits in a private New Haven collection, she has pictured East Rock from afar, and it takes a viewer a moment to get their bearings. There’s a delight and a challenge there, in having to see something that one passes every day with new eyes.

Lindroth, whose exhibition of large polaroid portraits is currently running at the New Haven Museum, said she would like to organize a retrospective of LaPalombara’s work at the museum. It feels fitting: during her lifetime, the artist featured in group and solo exhibitions at the Arts Council of Greater New Haven, New Haven Lawn Club, DaSilva Gallery, the Institute Library and Hamden Hall, Smilow Cancer Center, New Haven Museum and many others. Her work is also in collections across the globe.

“She was arguably the most sincere person I have ever met,” Joseph said. “I must say that both her paintings and our looking at paintings together were for me a huge education. She was, I think, as good a critic of her own paintings as well as the paintings of others. She was also very honest and straight-shooting and she was a tough but honest critic.”

“I miss her profoundly,” he added. “It’s [the sentiment] not meant just to be beautiful. It is honest. It is honest. It is what she would have preferred.”

Donations in LaPalombara’s memory may be made to Creative Arts Workshop or to the National Audubon Society. Hank Paper, the founder and original owner of Best Video and Cultural Center, came up with a list of films and t.v. shows for New Haveners to watch in her honor. Find that here.