Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills | Arts & Anti-racism | B*Wak

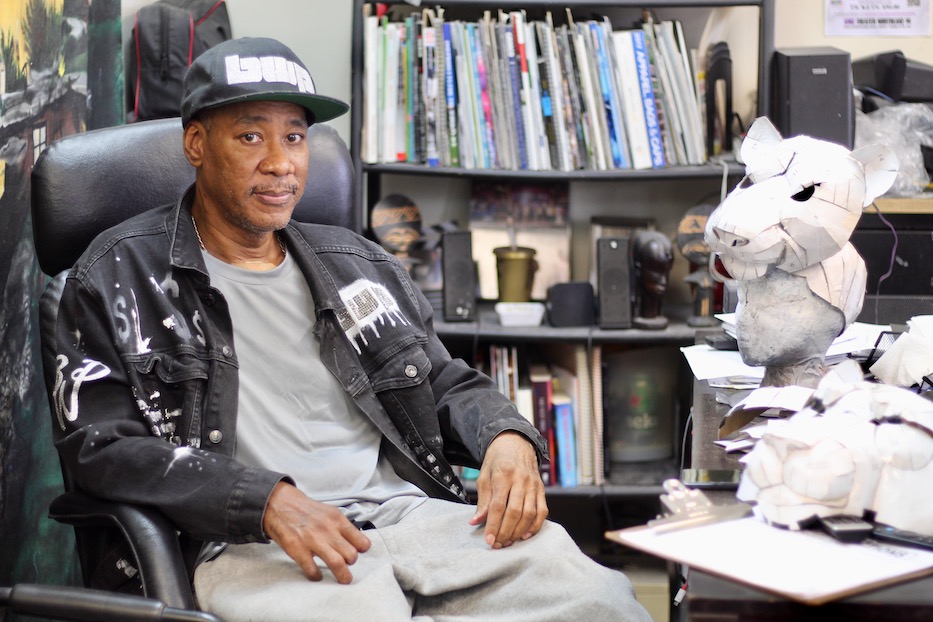

Edmund “B*Wak” Comfort in his studio at 300 Whalley Ave. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Illness tried to take one of New Haven's most beloved artists well before his time. Now, the community is rallying around him as he starts a new chapter on the road to recovery.

That artist is 55-year-old Edmund “B*Wak” Comfort, who for decades has graced the Elm City with his murals, vibrant tapestries, art business B*Wak Productions and dozens of youth programs. Since March of this year, he has been fighting for his life—and his work as an artist—after a bout with the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae left him with multiple amputations and a small mountain of hospital bills.

To offset the cost, he has launched a GoFundMe, and is joining A Broken Umbrella Theatre for a comedy and improv fundraiser on Saturday, Aug. 26 at 446A Blake St.

"I'm looking at, like, where is my career going to lead to? What is God using me for?" he said in a recent interview at his studio at 300 Whalley Ave. "I thought he used me to tell my story through art. I think I'm wrong! He might want me to tell my story through another form. I'm amazed. I'm amazed and eager to see where the next chapter leads me."

Tuesday marked his first time back in the Whalley Avenue studio since late March.

His recovery, which is still ongoing, has followed months of uncertainty and a brush with death that haunted the artist for weeks. At the end of March, Comfort was "unstoppable, at the top of my artistic game," he remembered. On a given day, he would work on painting and remodeling his uncle's kitchen, laying down the new floorboards in a friend's basement, and airbrushing t-shirts in his studio at night. He felt like he could take on anything.

Then he went to a party with a friend. A few days later, he felt like he'd come down with a bad case of the flu. He was tired, with a stomach ache. At first, he didn’t think anything of it.

"I started treating it like a common cold," he said. But nothing got better. His ankles and feet started to swell, until they were brick-hard, cold to the touch and heavy when he moved. When Comfort walked across the wood floors of his home, they made a solid knocking sound that his wife could hear from another room. By the time he decided "I can't take another day of this," they were turning pitch black.

His wife, Shannqueta Sanders Comfort, rushed him to the emergency room at St. Raphael's at 3 a.m. on the very last day of March. When he woke up, he thought he'd been out for a few days. In reality, two weeks had passed. He was intubated, with tubes coming out of his mouth that made it impossible to speak (he later had a tracheostomy tube, the scar from which is still healing on his neck). Around him, a steady stream of friends, family and longtime collaborators came to visit. Sanders Comfort, who was also caring for their five-year-old daughter, barely left his side.

"The good lord got me through," he remembered. "When I woke up, I could only move my eyes. I couldn't move my body. At that point, I did realize that I did have a connection with God. That's the only way I made it."

As he spoke to doctors, he learned that the bacterial infection had nearly killed him. Streptococcus pneumoniae had led to septic shock and something called disseminated intravascular coagulation, in which the body starts developing blood clots across the bloodstream. Illness attacked his feet and hands, resulting in a double amputation beneath the knee, and the partial removal of four fingers on his right hand.

The silkscreen presses are just as he left them.

Overnight, it felt as if his world had been turned upside down. He tried not to despair, he said. Instead he started thinking about how and on what timeline he was going to return to art.

After his amputations, doctors transferred Comfort from Saint Raphael’s Hospital to the nearby Grimes Center, where he learned to walk on prosthetic legs in four weeks of inpatient physical therapy. He credits his faith, as well as the constant care of Sanders Comfort, as two larger-than-life forces that helped pull him through.

Along the way, he managed to endear himself to every staff member who came through the space, as well as several of his fellow patients. Sanders Comfort remembered a roommate who refused to get out of bed until Comfort arrived. When he began walking, the roommate got up too, she said. By the time Comfort left, the roommate was walking on his own.

Now, he's trying to figure out what his limitations may be as an artist. As he's recovered, Comfort has thought a lot about his love for education, and the ways to teach young artist-entrepreneurs as he gives his body time to heal. He's gotten back enough use of his right hand to hold an airbrush and paint can, but is taking it one day at a time, he said. As he returns to it slowly, he plans to type, do digital graphics, silk screen and heat press.

Teaching already feels intuitive for him, he added. Comfort's origins as a community-focused artist go back to the early 2000s, when he started teaching set design and theater at Roberto Clemente Elementary School in New Haven's Hill neighborhood. During those years, he spent his weekends at the Harlem School of Art, then commuted back to New Haven to teach during the week.

It was on a field trip to Long Wharf Theatre with his students that he realized he could be building professional sets without ever having to go into Manhattan. Long Wharf led him to the Yale Repertory Theatre, which led him to Lyric Hall. It was there that he met A Broken Umbrella Theatre (ABUT) company members Ryan Gardiner and Ian Alderman, and reconnected with longtime member Matt Gaffney.

While his set design still occasionally took him on the road—he fondly remembered a fellowship out in California—the Westville-based ensemble soon had his heart.

"I've probably worked with them on every single show," he said with a faint smile. After doing load-in on VaudeVillian at Lyric Hall, he lent his skill in design, carpentry and visual arts to ABUT dramas that criss-crossed the city, from Edgewood Park to Erector Square. Over the years, he worked as a carpenter on Play With Matches, airbrushed the windows for Gilbert the Great, assisted on building sets for the Library Project, among many other productions.

He was always ready to help, said Gardiner. Last year, he partnered with ABUT The Shack, and the artist Isaac Bloodworth to design and paint an installation on Blake Street that is still standing, hanging on the side of the road like a bright welcome to the neighborhood. He said it was probably the last public project that he worked on.

"At this point, I'm really trying to see what I'm actually capable of doing," Comfort said. "I'm healing right now. But I suspect I'll be able to airbrush again. I would like to be more patient [with healing] but life has me going here, going there ... so I'm just taking it in stride."

"There are times I get depressed," he added. "But I snap out of it. Reality is, they're not gonna grow back. I'm not a lizard. I'm hopeful to get stronger. I'm hopeful that I'll continue to walk how I did. I always think, it could have been worse. So I'm grateful. Always grateful. And I just love life."

Meanwhile, community members are working together to make his recovery a little easier. Since going into the hospital, Comfort has lost months of income after years supporting himself and his family. He said that his application for disability was denied, meaning he needs to appeal his claim. That process can take months, with the cost of a studio and a home hanging in the balance.

While he’s getting stronger each day, he also still contends with phantom limb pain and the limitations of needing to slow down. The GoFundMe and upcoming ABUT fundraiser are there to help fill a gap.

His peers, meanwhile, are excited to help. In a phone call Friday, ABUT Artistic Director Ruben Ortiz remembered meeting the artist roughly 12 years ago, and learning that he could count on his skill, wit, and humor every time A Broken Umbrella had a show. When ensemble members heard that Comfort was fighting for his life, a fundraiser seemed like a no-brainer.

"It was just an opportunity to help one of our own," Ortiz said in an interview Friday. "He has such amazing spirits. You think of everything that's happened to him, and he can be so positive."

"He's such a vibrant artist, and he's going through such a major physical issue that he's going to be navigating ... it's really challenging," Gardiner added. "So we're just trying to give a little bit of support in terms of what he's experienced over the last three months."

On Tuesday, Comfort sat in his studio, looking around at a space he hadn't visited since March. It was, at times, as if the room had been suspended in amber: a trio of screen printing presses still sat with color inked onto their surfaces. A quartet of respirator masks hung from a shelf, collecting dust.

At the far end of the room, a drop cloth sat completely dry, beneath a tapestry the artist had been working on months before. Bottles of thick acrylic paint, some half-used, sat at the ready on one side of the room. Sun streamed in through a window. At his desk, Comfort looked through piles of papers. An unfinished mask sat to his left, making the shape of a lion's head.

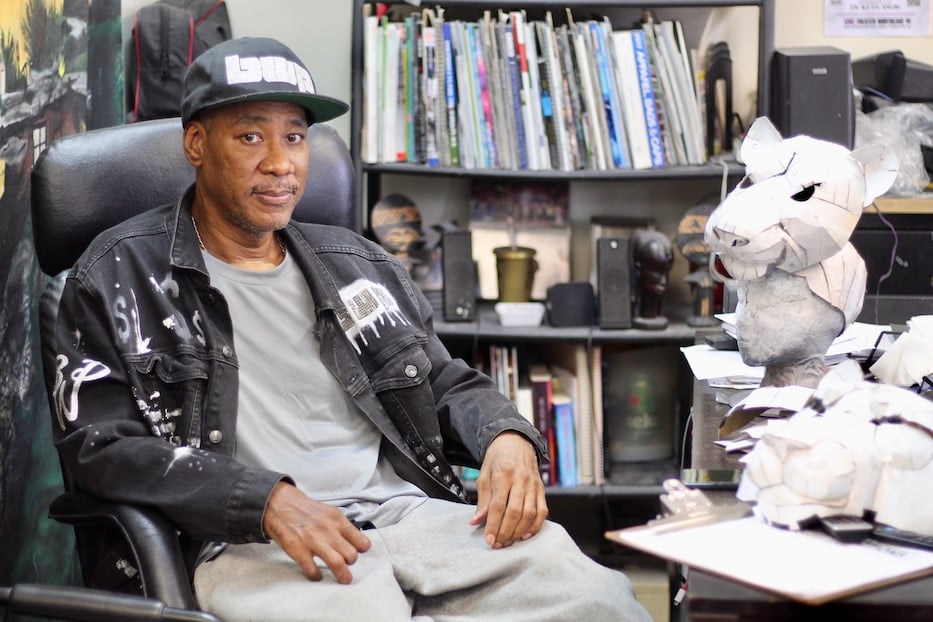

William Moore and Edmund “B*Wak” Comfort.

William Moore, a multimedia artist who has a studio next door to Comfort's, gave a little knock on the door before he came in, beaming when he saw Comfort. "Hey chief!" he said. "I saw your light on!"

"That's what's up!" Comfort said. He lifted himself carefully from the chair where he sat, and walked methodically over to Moore. Steadying himself on the desk for a moment, he embraced him. "This is my first time being here since ... since I left. It's a good feeling."

Moore, whose mom attended high school with Comfort, said he's glad to have his friend and role model back. In addition to working down the hall, he teaches martial arts and karate downstairs, at 302 Whalley Ave. The building felt lonelier knowing that Comfort wasn't there.

"I need him alive! I need him around," Moore said when asked how it felt to have his friend back in the building. "He's one of my favorite people. He got more talent that I need to catch up on."