Culture & Community | East Rock | Arts & Culture | City Gallery | Arts & Anti-racism

Taylor Ikehara Photos.

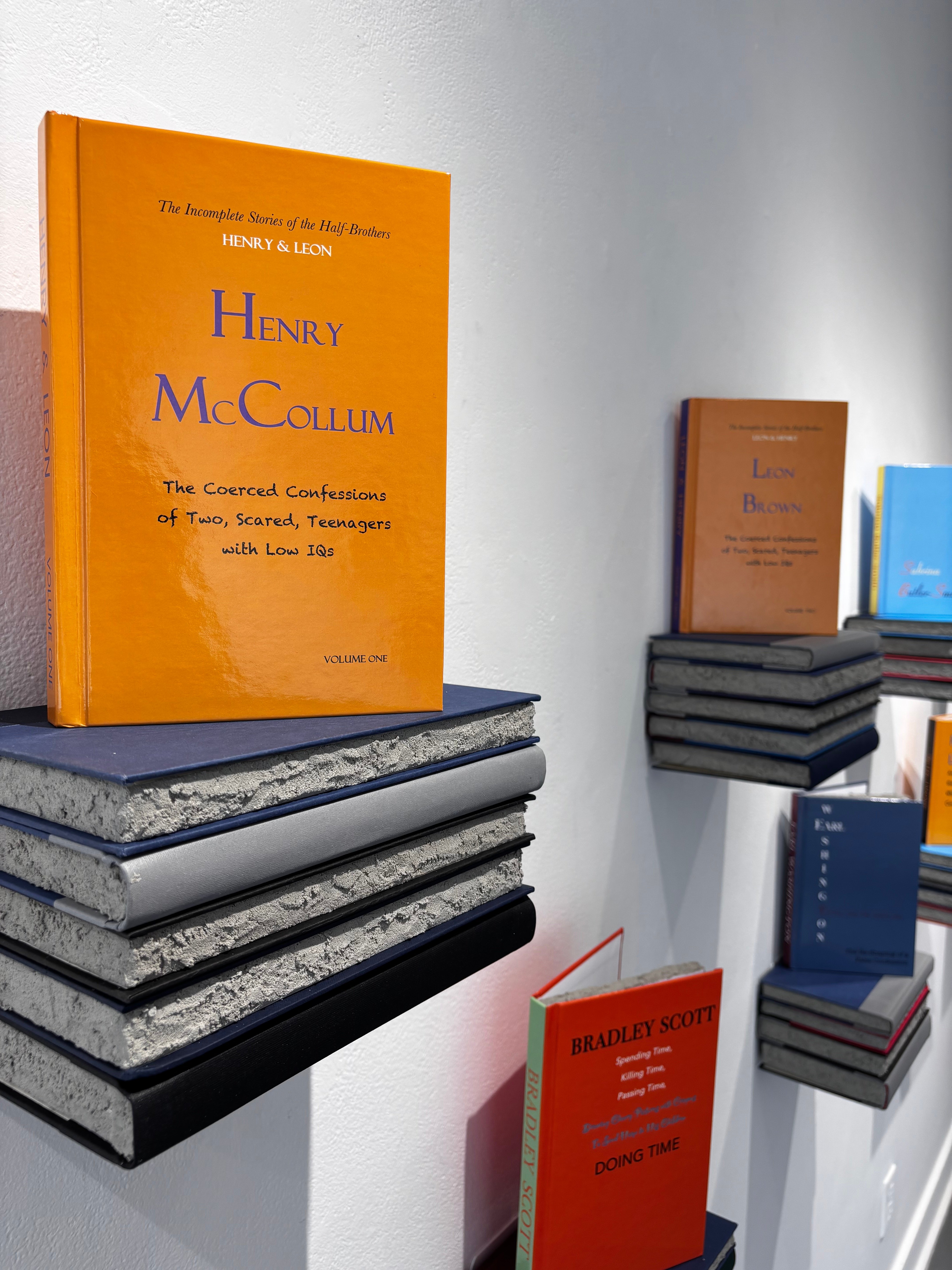

The rattle of A/C through the floor grates at City Gallery is a pleasant and somehow appropriate background sound for the art on display. Walking in, there are small stacks of books, each one cemented shut, jutting out from the walls on either side of the gallery. Each stack holds an additional book. Each one has a name on it, as well as a subtitle; each appears to be a biography. Visitors are encouraged to pick them up and look inside. But you can’t read them—they have been cemented shut.

“Closed off; their lives have been closed off,” Meg Bloom, an artist at City Gallery, said of the art piece.

“Biography: Unwritten” is just one part of Served: Wrongful Convictions & The Death Penalty, an award-winning art installation at City Gallery by conceptual artist Toby Lee Greenberg that runs through August 24. “It’s 20 years in the making,” Greenberg said after a photoshoot on Tuesday.

The names on each “biography” are real; each person represented was wrongfully convicted and incarcerated, only to be exonerated years (and many times, decades) later. Inside, past the cement pages, visitors can find lengths of their sentences and other details, which are preceded by a simple prompt. Each one begins with, “Missed,” describing what the person missed during their sentence.

One reads, “Missed learning how to drive a car.” Another: “Missed attending his son’s funeral.” Another: “Missed a life without regret.”

Noticeably absent from the biographies is any detail involving the crime itself. According to Greenberg, this is intentional. “They’re innocent,” she said. “I thought to myself, why mention what they’re convicted for?”

Greenberg said that her inspiration for the piece began when she was doing research for “Last Meal,” another series that is part of Served. While combing through databases such as the Death Penalty Information Center and the Innocence Project, Greenberg became curious about people who are convicted of crimes they did not commit.

“I thought it was this rare thing,” she said. “Only to find out it happens all the time.”

Her research into the lives of exonerees, often consisting of old newspapers, and going back past their convictions, allowed her to learn the facts that make up the subtitles and “Missed” prompts of each biography.

Served calls into question the use of capital punishment in the United States and highlights the sheer scale of wrongful convictions, which disproportionately affect Black people. Data from the Innocence Project shows that, on average, people wrongfully convicted of a crime serve 16 years before their exoneration.

The artist in front of her "Last Meal" series.

Since 1973, at least 200 of the people who have been exonerated have been from Death Row. The Equal Justice Initiative estimates that for every eight people executed, one person on death row has been exonerated. Putting it in perspective, the United States has the largest prison population in the world, making up five percent of the world’s population while having 20 percent of all people incarcerated in the world.

“Between the police, the prosecutors, and the media,” Greenberg said, “Once your image appears on the news, the chances of getting a fair trial are pretty slim.”

Past the books, encompassing an entire wall, is the death warrant of John Arthur Spenkelink, the first “unwilling victim of capital punishment” after capital punishment was reinstated in the United States in 1976. A frighteningly stark photograph titled “Prepared for Execution” is nearby. The picture was taken behind John Arthur Spenkelink’s head; nothing of his face, no facial feature or expression, can be seen.

“The Menu” stands just off to the side—it’s a real menu, another interactive art installation that allows visitors to page through the last meals of prisoners before their execution. The details of each prisoner’s last meal vary, much like the “Missed” prompts.

Some are extravagant, but, soberingly, they are just as often requests for comfort food, sometimes pulled from childhood memories. One is simply “Two boxes of frosted flakes, pint of milk.” Humanity is evident in each request, and in the differences between them.

Some are extravagant, but, soberingly, they are just as often requests for comfort food, sometimes pulled from childhood memories. One is simply “Two boxes of frosted flakes, pint of milk.” Humanity is evident in each request, and in the differences between them.

“I like to lure people in, make them think they’re looking at something else,” Greenberg said.

Some of these meals have been printed on plates and adorn the wall next to the death warrant. One, for instance, flanks a picture frame and hangs above a table with a fork and a piece of pecan pie on a plate. This is “Last Meal and Saved for Later, Never Eaten.” The plates of “Last Meal” are identical, save for the details of the meals it is easy to imagine them serving.

The picture frame above “Saved for Later, Never Eaten” explains the pie. It was common for Ricky Ray Rector to save his dessert until bedtime. After a self-inflicted gunshot during his arrest, he was lobotomized in order to save his life, despite the fact that he was then made to stand trial, and was sentenced to execution. The fact that he left his pie out on the day of his execution underlines the argument that he did not understand what was happening.

Opposite this wall is one of the most striking pieces of the installation: a plate just like the ones in “Last Meal,” only shattered into several pieces. The piece, presented as a triptych and titled “God’s Saving Grace, Love Truth, Peace, Freedom” was, according to Greenberg “a happy accident.”

The plate fell and broke during an installation, but Greenberg’s son encouraged her to keep it anyway. In the show, gravity’s effect on the plate opens new windows of meaning just as clear as the cracks themselves; it’s easy to stand silent in front of the piece and see something new every time.

Exiting the gallery and walking past “Biography: Unwritten” again, the display lights shine down on each biography and the books that hold them up. They cast a square-like shadow underneath and it’s hard to ignore the fact that, for all the world, the shadow looks like a tombstone.

“I want people to look at them as if they’re real biographies,” Greenberg said. She held a biography in her hand for a moment. “I like the weight of them—I want people to feel that weight.”

Served has won several awards, including “Best In Show” earlier this year at the 62nd Annual Juried Competition at the Masur Museum of Art in Monroe, Louisiana. “Biography: Unwritten” is an ongoing project—eventually, Greenberg wants to make a biography for all 200 people exonerated since 1973.

In the meantime, before a show in Philadelphia next month, she will be at City Gallery this Saturday and Sunday for Served’s last weekend. So come talk to her about her art, and consider making a donation to the Innocence Project here.

City Gallery is located at 994 State St. in New Haven's East Rock neighborhood. The gallery is open Friday through Sunday, from 12 p.m. to 4 p.m.