Culture & Community | Immigration | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

Barongozi last year at the Folk Fest he and Jisu Sheen mounted at Havenly. Lucy Gellman File Photo.

Kulimushi Barongozi was 13 years old when he discovered that his best communication happened through visual art. Now, he's using that belief to inform his latest project, a book and art project based on collective storytelling.

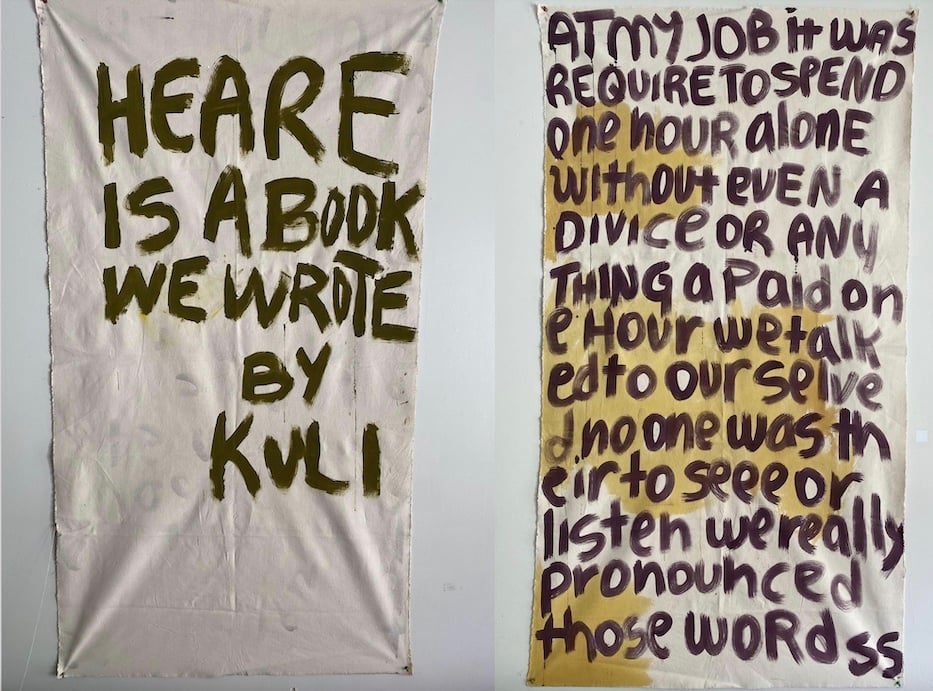

An artist and educator in New Haven, Barongozi is the co-founder of the Second Floor Hardware School and a working artist in the city, where he teaches classes with Leadership, Education, Academics in Partnership (LEAP). Most recently, he has started work on Heare is a Book We Wrote by Kuli, a series of miniature stories on canvas about existing in and engaging with different spaces and environments.

“Art just fits my personality… the other jobs that exist out there, I never found any passion in them,” he said in a recent interview in his living room.

An immigrant from the Congo, Barongozi— known more often in New Haven simply as Kuli— has been making art for 20 years. As a teenager in Baltimore, he was drawn in by the routine of his high school art class, and his admiration of the students who made comics and doodles in their notebooks. There was also no language barrier: he consistently received positive feedback for the artwork he created at school, when subjects like English or math seemed more inflexible.

It made him feel more confident in pursuing more inventive projects, he said—including and especially writing. As his English improved, Barongozi began to view assignments like essays the same way he viewed his art. He tried taking liberties, like purposely misspelling words or using incorrect grammar as a means of expression. When he received poor grades in school for taking chances with language, he continued the approach more expansively in his art practice.

Barongozi went on to major in international relations at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania. It led him to study the confluence of migration and art, an interest that still appears in his work, and especially his detailed and lush portraits of family in the Congo. During those years, he also built a kind of personal belief system around art—that it was much more expansive than putting a paintbrush to canvas or linen, and was in fact a universal language, applicable across media.

“If your friend invited you over to make art, what would you think of?” he mused. “Maybe painting and drawing? For me it could be anything, like movement or even cooking.”

For Barongozi, that’s even true of labels: he doesn’t go out of his way to call himself an “artist”, and only accepts the label because peers, friends and colleagues call him one. In fact, he said, he doesn’t especially like the title, and will often deflect the question if someone asks if he’s an artist.

Although Barongozi might not call himself an artist, his apartment looks how one would expect an artist’s apartment to look. Paintings hang up on the walls and along the floor. Several stacked together against a wall liven up an already bright and eclectic space.

On the floor of Barongozi’s living room sits a giant painting, with bright hues of red, pink and blue swirling around a strong, stoic face in the center of the canvas. The face, meanwhile, is made up of an array of choppy, colorful brushstrokes, colors that form a deep brown when mixed together. There are a few more sketches of smaller faces scattered across the portrait.

Sebastian Ward Photos. All artwork by Kulimushi Barongozi.

It tells the stories of his family. Barongozi just recently returned to New Haven from the Congo, where he spent time working on stories and visiting family. The centerpiece of the painting is his late grandfather’s face, transmitted onto the canvas directly from his memory.

His grandfather passed away shortly after he left the Congo, and the painting was a way for Barongozi to both mourn and explore memories that are very personal to him and his own lineage. The portrait also features sketches of his grandmother and some other blind faces, harkening back to his admiration of doodlers. “I always doodle on my paintings.”

“It makes me think, ‘Wow, I came from this, and this person just left … and I’ll be leaving soon too.’”

Barongozi’s most recent work is a book entitled Heare is a Book We Wrote by Kuli. The project began with the artist’s desire to write a book in less than five minutes, and started with a paragraph written hastily on the back of a canvas. The book eventually became a compilation of these paragraphs, stories and poems, which double as documents of Barongozi’s daily life.

The “Heare” in the title is a combination of the words “Here”—because it is right here and right now—and “hear,” because the book contains a few written songs. He emphasized that “we” wrote the book because writing does not feel like an “I” activity. He feels like different versions of himself contributed to the project, and so did the people he drew inspiration from while writing it.

“Everything isn’t just one way; like multiple pronouns, there are many different versions of Kuli,” he said. “ I get energy and phrases from people. If you say something I like I’ll write it down, so you contributed as well.”

Fellow artist Jisu Sheen, the other co-founder of Second Floor Hardware School, remembered meeting Barongozi through a friend, and then reconnecting with him during a protest on the New Haven Green in spring 2021. After making time to draw together, the two mounted a show at Volume II: A Never Ending Books Collective on State Street last year, and then their first “Folk Festival” at Havenly a year ago this month.

“Now everytime we get together, we make something,” Sheen said in a recent interview. “Whether it’s drawing, a song, or even art show plans”.

She added that the Second Floor Hardware School does not exist as a physical space yet—the name is aspirational—but already encompasses many activities and aspects. “It can be a school of sorts, a studio, or just a place where people can hang out, dance, and make art.”

With Barongozi, she is excited to be planning the second iteration of the folk fest, currently titled “Infinite Gohyang.” The title is based around Gohyang (고향) the Korean word for “hometown” “

“It’s anything that invokes comfort, familiarity, or nostalgia,” she said. It’s a word that carries weight for them here: both have spent the past few years making New Haven their home. “New Haven can feel like a hometown even if it is not the town you’re from. Being away can make you feel nostalgic, like you miss home.”