Education & Youth | High School in the Community | Arts & Culture | Wooster Square | History | Robert Greenberg

Top: Sara Sportman, Scott Brady, Debbie Surabaian. Bottom: High School in the Community junior Soroya Flowers.

Soroya Flowers peered into a hole that had appeared in her school’s parking lot, curious to know the 250 years of history that lurked beneath the surface. Just a few yards away, State Soil Scientist Debbie Surabaian and archaeologist Krista Dotzel pushed a three-wheeled ground-penetrating radar (GPR) machine, watching its screen for spots of color. At the center of the lot, historian Rob Greenberg buzzed around the space, too excited to stay still.

Monday morning, all of them gathered outside High School in the Community to confirm whether Arnold, who went from darling of the American Revolution to a loyalist traitor, briefly owned a house at 159 Water St., where a surface lot now sits across from the high school. Greenberg, founder of Lost In New Haven, believes that he did—and hopes to turn the lot into a living archaeological site for students across the city. He is comparing it to the La Brea Tar Pits in California.

If he is correct, the lot covers the back wall, basement, privies, and smuggling tunnels of Connecticut’s favorite turncoat. He added that the property’s owner, Betsy Henley-Cohn, has offered to donate the space to Lost In New Haven if it becomes an active site. She did not reply to a request for comment for this story.

Rob Greenberg with Debbie Surabaian and Krista Dotzel.

“I feel like New Haven is losing the essence of its history,” he said Monday, as Surabaian unloaded a ground-penetrating radar machine onto the HSC parking lot. “I want students to understand what’s sitting in their lot. I want them to have a sense of place. I want them to realize where they live is this historical time capsule.”

In the Monday morning chill, he watched as a number of archaeologists, anthropologists, and history nerds unloaded ground-penetrating radar (GPR) from the Office of State Archaeology, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS), and Friends of the Office of State Archaeology (FOSA-CT). They included State Archaeologist Sara Sportman and public historian Laura Macaluso, with whom he has been working closely for years.

The project has fascinated him for at least a decade. Ten years ago, Greenberg started looking at old maps of New Haven, trying to piece together the story of a house Arnold built in 1769 and lived in briefly before serving in the Revolutionary War. At the time, “it was the grandest house in New Haven,” he said, lifting a sepia-toned photograph of a wood-frame house with front windows, a picket fence, and a tree in the front yard.

Arnold moved out of the house during the war, and it was sold in 1779. By then, he was well on his way to becoming the pile of loyalist slime that New Haveners know him as today. Over 15 years after Arnold moved out of the house, Noah Webster moved in. Greenberg believes he penned his now-famous 1806 dictionary, titled A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language, “right in the foyer.” From a stately home, it later became a lumber company and was then demolished around 1909 or 1910.

“If it was George Washington’s house, this wouldn’t have happened,” Greenberg said bitterly as a 274 bus rumbled by, unaware.

After comparing old maps of the city with contemporary GPS data, Greenberg believes the back of the house is at 159 Water St., which sits across a sprawl of asphalt from High School in the Community. When an old warehouse on the lot that sported Hi-Crew’s storied graffiti walls came down five years ago, Greenberg dug a hole beneath the concrete, finding shards of glass bottles and a pipe. Monday, they sat out in plastic bins beside an old uniform of the Governor's Foot Guard, of which Arnold served as its first commander.

In the lot, Dotzel and Surabaian began making a survey grid, marking every half meter in thick white chalk. Sportman and Scott Brady, a volunteer with FOSA-CT, canvassed the area with a length of measuring tape. Walking along those chalk lines, they began walking each line from South to North.

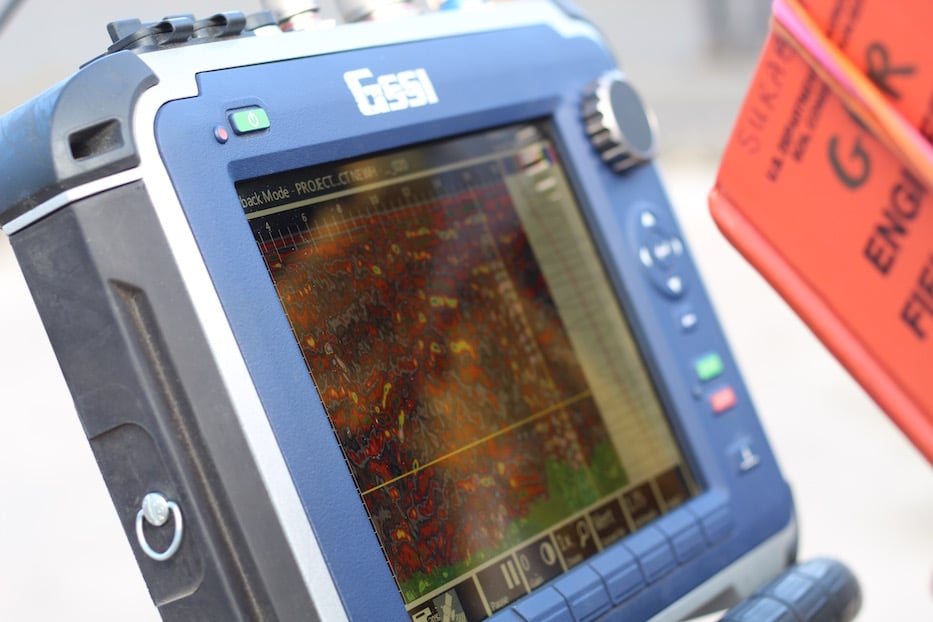

The GPR goes three meters deep, which Surabaian said is enough to look for significant soil disturbances and differences in texture. Dotzel, an archaeologist with NRCS who started in September, studied Surabaian as she maneuvered the machine.

“I think it’s grand fun!” she said. “This is why I’m doing this. We can use scientific methods to check folklore.”

Ground-Penetrating Radar in progress.

Every so often, Surabaian called Greenberg over to look at her findings. A constellation of red, green and yellow smears represented the layers of soil beneath the ground.

“Could this be an extension of the stone?” she asked Greenberg at one point, standing to the right of center in the lot.

“The front corner of the house I think is somewhere around here,” he said.

Macaluso’s eyes twinkled as she watched. Five years ago, she started giving a presentation on Arnold’s life that has since grown into a Benedict Arnold Memory Project. At some point she linked up with Greenberg, and started working to get the Office of State Archaeology out to the site. The process hit pause when State Archaeologist Brian Jones passed away in 2019. Months later, the pandemic hit.

When they finally secured a date, Macaluso made plans to make the drive from Virginia, where she currently lives. Earlier this year, she penned an article on the subject, tracing Arnold’s complicated and temperamental history through the houses he owned. When people ask her the question “why remember a traitor,” she points to Arnold's role in winning the battles of Saratoga, Fort Ticonderoga, and Fort Stanwix.

“One thing to remember about the American Revolution is that these homes represent a very small sliver of revolutionary life,” she said. “To not know what a loyalist house looked like—it belongs in the conversation.”

Top: Thaddeus Reddish and Assistant NHPS Superintendent Dr. Paul Whyte. Bottom: Sophomores in Ben Scudder’s U.S. History class.

Every so often, high school history students burst out of the school’s side doors and into the cold. A little before 11 a.m., Greenberg gathered students in Ben Scudder’s U.S. History class around him. He raised his hands as if he was about to conduct a symphony.

“Have any of you ever heard of Benedict Arnold?” he started. There was silence. He sketched his own path to finding Arnold’s home, including the discovery of an apple orchard where HSC now stands. He held up fragments of glass bottles from his first dig at the site.

“Do you want to see the hole?” he asked. Students burst into enthusiastic declarations of “yes,” puncturing the silence, and trotted over to a wide hole in the concrete with dirt and piping hanging below. Several lingered around the space, in no particular hurry to get to fourth period geometry class.

“It’s cool to know that we’re on something so ancient,” said sophomore Elijah McClain.

“I want to know what it is, where it’s located,” added Elijah Mercado.

HSC sophomores Elijah McClain and Elijah Mercado.

Flowers, who is a junior, peered into the hole and tried to make out shapes. Growing up in New Haven and Hamden, “there’s so much history that nobody talks about here,” she said. She likes feeling like there is a whole untold story of her city just waiting to be unearthed beneath her feet. After spotting the taped-off section when she pulled into the lot that morning, she wanted to get the scoop.

“I’ve always liked history because it gives us a refresher of where we came from,” she said. “There’s history everywhere.”

As they headed back to class, a steady stream of visitors came through the space. Site Projects Director Laura Clarke, long a supporter of Greenberg’s work, praised the project effusively as she watched its progress. Ben Berkowitz joked that it had the makings of a Benedict Arnold Skate Park. Aaron Goode, a self-described “huge nerd” and head of the New Haven Votes Coalition, ran through the depth of Arnold’s treason not only on a national level, but also on a local one.

Greenberg, State Soil Scientist Debbie Surabaian, State Archaeologist Sara Sportman, and Scott Brady. Macaluso is pictured at the right.

“The way I’d tell the story, he was very invested in New Haven,” Goode said. “It’s not just that he betrays his country, it’s that he comes back here in 1779 and he burns the town. How can you burn the houses of your friends and neighbors? It doesn’t get more jerky than that.”

Thaddeus Reddish, now the director of security for the New Haven Public Schools, didn’t see it quite that way. Growing up in New Haven, Reddish could see the Winchester Repeating Arms Company from his house, and wondered what history sat under its heavy brick foundation. As a kid, he loved digging in the family’s dirt backyard, a habit that came to an end when his dad paved it over while he was at school. Monday, he rolled up to see if the site was taped off correctly, and stayed to watch Greenberg’s progress.

Reddish said he sees history as a living thing, and loves the idea that Arnold lived at 159 Water St. As a recruit at the New Haven Police Academy under the now-legendary leadership of K.D. Codish, he took trips to the New Haven Museum and Afro-American Archives on Orchard Street as part of his training. When he became assistant chief of the New Haven Police Department, he got used to looking at a historic painting of Daniel Webster’s house during department meetings. When the stucco came off of his house to reveal cobblestones this year, he explored the stonework and let them be.

“I think this is great,” he said. “I think this is how it should be preserved. We should be able to lift this up.”