Food & Drink | Jules Larson | Shake Shack | Arts & Culture | New Haven | Visual Arts

Art25 Photo.

Art25 Photo.

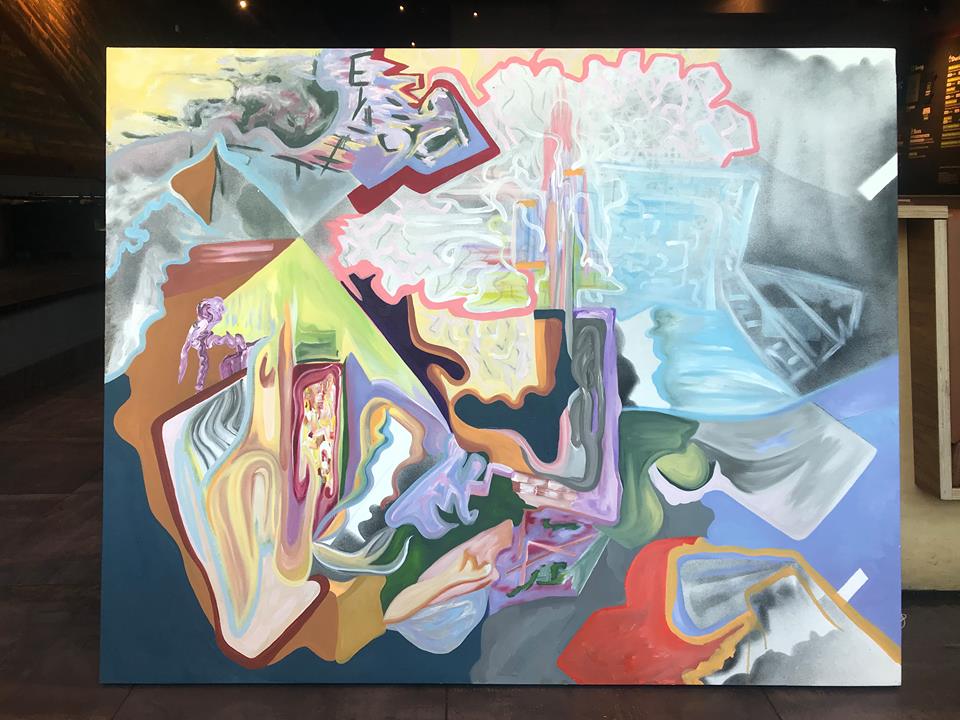

There isn’t a starting point in Parry, because there are many. Maybe it’s the center of the canvas, where thick white acrylic wraps a blue shape that looks like a tooth. Or the upper lefthand corner, where a loud pink and purple half-moon—or maybe it’s an afro pick?—interrupts a block of blue and green spray paint. Or in the lower register, where a fat yellow ribbon of paint looks like it might unfurl, or curl inward forever.

There’s only one thing the artist will tell viewers for certain. The work should always be accompanied by the thick smell of cheese fries. Piping hot, just the way she likes them.

Larson introduces musicians Quinn Harley and Ian Biggs during the opening. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Larson introduces musicians Quinn Harley and Ian Biggs during the opening. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Parry marks the entrance to Jules Larson’s new exhibition Twenty-Seventeen at Shake Shack, on view now through Dec. 1. A collaboration between Larson, Shake Shack and fledgling arts organization Art25, it marks the first of a series of exhibitions that will be held in 25 unconventional spaces, from burger joints to banks, in the next two years. Wednesday night, Art25 held an opening reception in the Chapel Street establishment, bringing in over 100 viewers in three hours.

Adam Shapiro, the restaurant’s regional marketing and communication manager, said that Shake Shake made sense for a first venue. In 2001, the now-national chain was born as a hot dog cart in Manhattan, during the public art installation I <3 Taxi in Madison Square Park. This is the first for New Haven’s outpost, but Shapiro said he hopes it won’t be the last.

“Public art is really in our DNA,” he said at the opening. “We see our shacks as a reflection of the surrounding communities, and this artwork embodies that reality.”

“We hope this is the first of many,” said JoAnn Moran, who co-founded Art25 four months ago with artist and friend Barbara Pochan.

The series, they explained, started as Pochan familiarized herself with downtown New Haven during her job at Gateway Community College. As she got to know the city, she said she found herself popping in and out of shops, restaurants, and storefronts, thinking about the amount of empty space they had on their walls.

Larson (center) flanked by Moran and Pochan. The painting Crave sits over their heads. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Larson (center) flanked by Moran and Pochan. The painting Crave sits over their heads. Lucy Gellman Photo.

“You try to make these [exhibitions] the best they can possibly be,” she said. “Because the art just makes the place look better. The goal is to really make a significant connection with these businesses and artists … where we can mutually attain our goals.”

“You can create these win-win-win situations,” she added. “It’s a win for the artist, for the organization [Art25], and for the business. It’s my observation that most people that aren’t in the arts don’t get exposed to the arts otherwise. Who takes time to understand how an artist makes a living?”

In that three-pronged win, Larson is the first artist to see what works, and where Art25 still needs to grow. Selected for her large, color-packed acrylic and spray paint canvases, Larson said that she sees the show as an opportunity to push accessibility, diversity, and inclusion in the arts—while leveling the economic playing field. She pointed to a deep segregation that she sees in the city’s visual arts scene, and suggested that holding a show at Shake Shack starts to break that down, by introducing the work to new and unlikely viewers in semi-public spaces. It goes with her style of public gallery: she has also exhibited at Koffee? on Audubon Street.

Meant. Acrylic and spray paint, 3 x 4 feet. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Meant. Acrylic and spray paint, 3 x 4 feet. Photo courtesy of the artist.

“I want art to be more casual,” she said at Wednesday’s opening reception, sitting before a steaming tray of cheese fries and bottles of red and white wine. “More accessible to people. I want people to see art and not feel like they have to be somebody to experience it.”

That’s based largely on the life Larson has led. Now 26, the artist grew up in New Haven, with stints in artist’s colonies including the now-shuttered Lehman Brothers building and Daggett Street Square. Now a student at Gateway, she lives in Fair Haven — but identifies with almost every neighborhood of the city, from East Rock all the way to the Quinnipiac River.

Pieces like Daggett, she said, reflect her trajectory as it is—with no reservations, and no do-overs. At Shake Shack, the work is mounted on the restaurant’s longest uninterrupted wall, between works Knell and Crave. From afar, a shape rises in the center, like a black stallion rearing and ready to go. Bright, red and pink forms swirl around it, malleable on their edges.

“I want to answer two desires in me,” she said. A constellation of vocals rose up from the front of the shop, where Quinn Harley was performing. “Where I started, but also where I’m going.”

She said she doesn’t specifically expect people to buy the works, which are priced between $200 and $1500. One of them, Paragraph, has already sold.

In the two years that went into Twenty-Seventeen, Larson has been experimenting with abstraction and media as a means of political and emotional expression. Perched on her shoulders are great teachers of expressionism and abstraction: Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Vasily Kandinsky, Jackson Pollock, Franz Marc.

They don’t come without some complications. As a trans woman, she said she recognizes the male-ness of that movement, and has made a point to learn about and pay homage to the women of the period. Women like Pollock’s wife Lee Krasner, whose career as a painter suffered in her husband’s shadow.

“Their gender is a huge part of how and why I paint,” she said.

It’s also personal, she said. In search of using her work as a mouthpiece for both social justice and personal growth, Larson is outspoken in her avoidance of identity politics, asking viewers to see her for the work itself, and not the gender of the artist who made it.

“I’m an artist and trans but I’ll never be a Trans Artist,” she posted earlier this week on social media. “My identities don’t create ‘inclusive’ gimmicks for the cut-throat art world or to sell art because of one facet of me. They are me, a part of me, and I’m always transforming in a lot of different ways and my art is deeply connected to how I navigate and want to change this world. I am a whole person.”

“When you start pigeonholing a certain identity as a prefix to its identity, you start really diluting the reasons why somebody might have made that art,” she added at the opening. “I transform with my work, and I transform in a lot of different ways besides just gender. I would like to stand on my own, rather than the idea that because I’m trans, I deserve all this attention. I would much rather than trans people gained housing, and better services, and better jobs.”

Crave . Acrylic and spray paint, 4 x 5 feet. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Crave . Acrylic and spray paint, 4 x 5 feet. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Larson said that she does see her work as “confessional,” an emotional catalyst and salve. She recalled sitting in New York’s museum of modern art at 14 years old, looking out on three Kandinsky paintings. Muted colors looked back at her, oil and canvass turned to muddled fruit before her eyes.

She couldn’t recall the names of the pieces, a practice that has carried over into her own aversion to titling works (she felt compelled to for this show, she said). But she had seen the pieces before, in the bright stickers that she had from museum gift shops.

She hadn’t imagined that she’d see the real thing. As she sat before the pieces, she started to weep.

“The stickers came to life,” she said. “It was emotional. I try to do that in my work.”

“It’s always me working through dysphoria, depression, anxiety in a really healthy way,” she added. “I want to push culture forward.”