Rachel Liu Photography

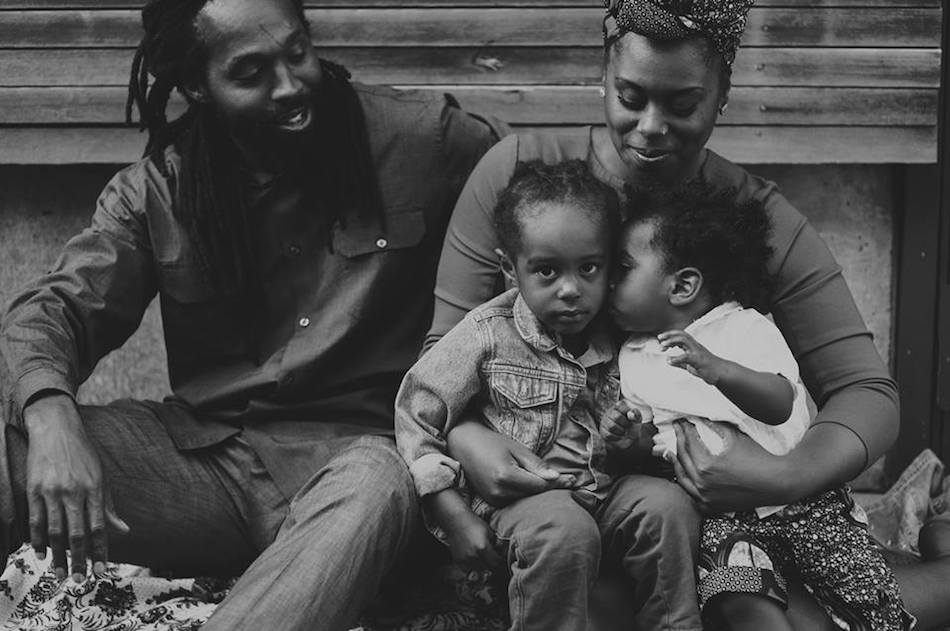

His two little eyes, just shy of trusting, are what stop you in your tracks. Around them, a young, inquiring face, with two neat plaits of hair on a head of fluff, and ears like seashells. Two miniature cheeks hold still his mouth, just downward sloping, with a poker face he’ll grow into.

The rest of the image opens up. The tiny denim jacket. His sister, pressing her soft face into his cheek and neck. Mom wrapping her arms around the two, hands clasped at their small bellies. She is gazing down; her eyelashes flutter just so. Beside her, dad looks on, a half-smile on his face. He reaches out his left arm, as if to say hey, let me get in on this hug too.

Liu. Lucy Gellman Photo

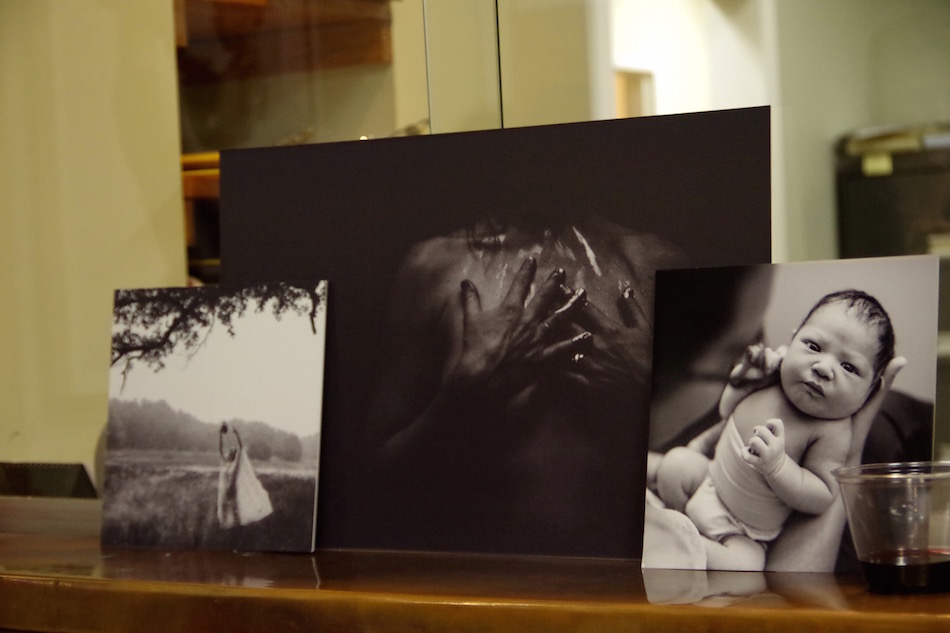

Caught in four different acts of looking, this family is just one of several in a new, untitled exhibition of Rachel Liu’s photography at Women’s Health Associates (WHA), a midwifery practice tucked away on the fourth floor of 46 Prince St. Originally mounted to celebrate National Midwifery Week (Oct. 1-7), the show does not yet have an end date. During the opening, Liu gave attendees chances to enter a raffle for a free photography session, and to donate to Puerto Rico relief efforts.

It’s one of the quirky, non-traditional gallery spaces popping up around the city—a waiting room turned art exhibition, for women and families who don’t want to leaf through musty, month-old copies of People or American Baby. WHA Director Laura Sundstrom, a certified nurse-midwife who took the helm after Debbie Cibelli’s death this February, said that she likes the idea of keeping it up for the foreseeable future.

“We wanted it to be thoughtful,” she said of the selection of photographs that showcase women and children, grassroots activists, grandmothers, and families. “Not just having images of pregnancy and birth,” but also of women and families in all stages of life, for WHA patients who may have difficult pregnancies, miscarriages, or complications.

Lucy Gellman Photo of Rachel Liu Photography

For Liu, it’s a personal bridging of worlds. The artist practiced as a doula, and then a labor and delivery nurse, for several years before going into photography professionally. From 2011 to 2015, she worked on the labor and delivery floor at Yale-New Haven Hospital. The hours were grueling, but she loved her work—almost as much as she loved taking photographs as a then-side-hustle. She also adopted her third child, Sol, and started to think about spending more time at home.

Then two years ago, she switched over to photography full time. Working from home gave her more time with her kids, and a more flexible schedule. But she said she doesn’t see the two professions as mutually exclusive. She's still slow and precise, with an eye on minute detail. And she still has a keen eye for babies—her own, and the ones she photographs in and outside the womb.

Rachel Liu Photography

“My children teach me every day … mostly to slow down and pay attention,” she said. “In that way they’ve really impacted my photography because I want to pay attention to how the light hits their hair, or how they’re holding something, or how they’re engaging with each other.”

The photos on display are meant to speak to that, she added. Contained within them are creation and community, teamwork and teaching. Liu has drawn heavily from two of her projects: a 2016 “Portraits of Protest” series that captured women after the 2016 election; and another called “Homecoming,” which depicts women “in the process of coming home to themselves.”

Funds raised from the first were donated to Junta For Progressive Action and Make The Road CT, both immigrant rights organizations dedicated to keeping families together.

Liu said she sees the works as telling a story that some other photographers—and mainstream media outlets—miss entirely. The photographs are distinctly more Sally Mann than Anne Geddes in this way, striking in black and white, with the occasional splash of color. There are, blessedly, no doughy white babies on oversized tulips here. They also go somewhere that Liu’s colleagues in the maternity field may not: Diversity and inclusion as a cornerstone of practice.

“Celebrating a really diverse family—that’s really important in my work,” she said. “To really portray lots of different types of families and how they come together. Black women breastfeeding, women of color breastfeeding, which sometimes doesn’t get shown as much as it should, women of different ages … I hope it helps paint a different picture.”

But Liu—and the WHA midwives with whom she worked for the exhibition—also acknowledges that the photos come at a fraught time for childbirth in the U.S., where the rate of maternal mortality is uniquely on the rise. As other developed countries continue to shrink their incidences of maternal mortality and morbidity, mothers across the U.S. are more likely to die after giving birth today than they were five years ago. According to a 2015 study in The Lancet, the rate has risen slowly for the past 25 years, from around 18 in 100,000 births in 1990 to 26.4 in 100,000 in 2015.

Doulas SciHonor Devotion and Natasha Ortiz. Lucy Gellman Photo

Midwifery, said Sundstrom, is helping to add nuance to that narrative. When midwives act in concert with a broader obstetric medical team, they create something called a birth plan, easing a woman and her partners or family through the process, and often reducing the rate of missing something that goes wrong during the birth.

They also help reduce the rate of cesarean sections, which can make vaginal births more dangerous during a second pregnancy and birth.

And as midwifery goes, New Haven is ground zero, with many midwives coming out of Yale School of Nursing as specialized certified nurse-midwives and around 150 certified nurse-midwives in the state. While the perception of certified nurse-midwives varies from state to state, WHA partner Kristin Nowak said that there is “a tremendous amount of mutual respect” among midwives and doctors in the city.

Kristen Becker, Laura Sundstrom, Kristen Wiley, Kristen Nowak, and Eliza Holland of WHA. Lucy Gellman Photo.

It doesn’t mean that she and the WHA partners don’t have to prove themselves to skittish grandparents or parents, though.

“We do a lot of stereotype-busting [at the practice],” said Sundstrom. “I think there’s this perception that we’re incense and candles—which are great!—but what people don’t recognize is that we practice individualized care. There’s an element of it that’s different [from routine obstetric practice], but there’s a lot of overlap.”

That stereotype-busting is all over the bright waiting room, where photos line the back wall, reception desk, side wall and hallway. Some photos are expected: babies, their mouths wide open, who still look small enough to fit in your bathrobe pocket. Mothers-to-be adorned with crowns of white flowers, holding their swollen bellies in bright silk gowns. Tiny bodies pressing themselves into engorged breasts, which are low and cross-crossed with dark veins.

But others, deliciously, are not. In one, an infant looks up at her mother with wonder and question, opening her eyes wide. She wears the littlest white jumpsuit, printed with giraffes. Her mother, looks down, face nearly obscured, a ponytail revealed.

In another, nurse-midwife veteran Paméla Delerme turns her body just slightly to the left, a long printed shawl around her shoulders. “I Love,” her shirt reads. She holds her hands, one on top of the other, above her heart. After 27 years in practice, she has been caught in an intimate moment, taking care of herself.

Delerme. Lucy Gellman Photo

It’s a photo that rings true to life, Delerme said. She first recognized her interest in midwifery over three decades ago, after a bad appointment with a gynecologist. Born to a teenage mother in New Haven, Delerme decided to go into the field to empower others, attending Wesleyan and then Yale University. She now does triage at Yale-New Haven Hospital, where “I put out fires all day,” she said.

“It occurred to me that I could do this with more competence from a very young age,” she recalled at the opening. “I decided on midwifery because the focus was on women and not sickness … empowering women and our strength.”

“People say to me: ‘You must love babies!’” she continued. “I take care of women … it makes me excited when a human comes into the world. It’s a sign of hope.”

To listen to an episode of The Tom Ficklin Show about birth on our affiliate WNHH radio, click on or download the audio above.