Culture & Community | Dia de los Muertos | Fair Haven | Arts & Culture | New Haven | Unidad Latina en Acción

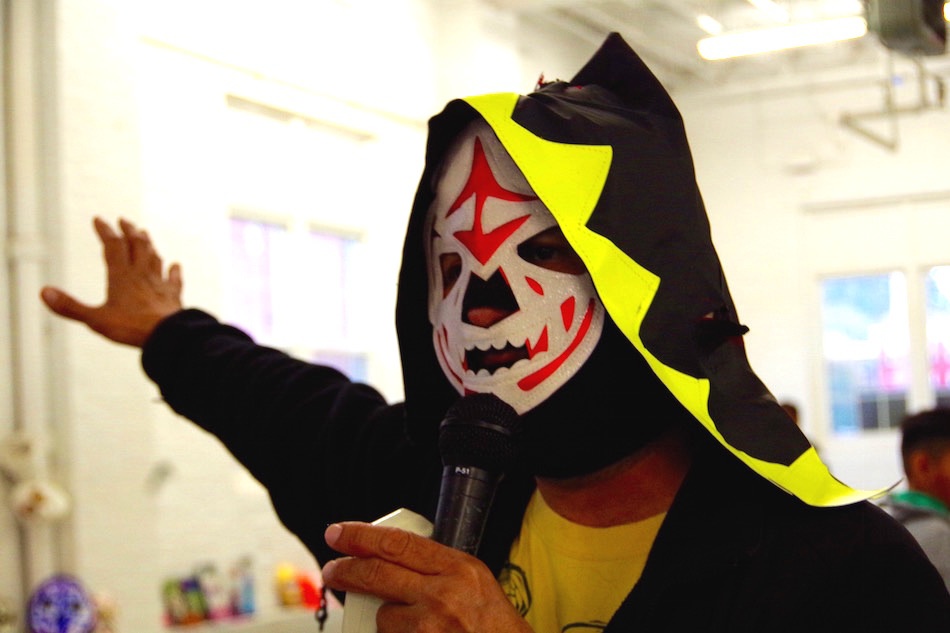

Suarez leads the charge. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Suarez leads the charge. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The larger-than-life calaveras were already dancing when five horns buried somewhere near the middle squealed, then came to life with a brassy, speakerphone-flecked version of Luis Fonsi’s “Despacito.” Up at the front of the line, 12 Soldaderas fingered their rifles, and looked directly ahead.

“Ni Una Más! Ni Una Más!” they cried.

This was the scene Saturday afternoon and evening at New Haven’s annual Desfile y Fiesta del Día de los Muertos, an annual parade and festival to celebrate the Mexican Day of the Dead. Sponsored and organized by Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA), the parade drew close to 300 attendees and several more onlookers as it wound through the streets of Fair Haven. An afterparty at Bregamos Community Theater, the parade’s terminus, went to the wee hours of Sunday morning.

The holiday is meant to honor and celebrate the dead, welcoming their spirits with decorative memorial altars, incense and candles, great fanfare and song. Saturday, those festivities started at 4 p.m. on Mill Street, where ULA members had been prepping the parade all week. Inside the warehouse where the group sets up, brightly painted larger-than-life Calaveras, and paper lanterns shared wall space with a “Viva la Memoria” (Live The Memory) banner and floats with dancing skeletons mid-movement on the sides.

As kids and parents alike prepared for the parade with elaborate face paint—many Catrinas, and at least one Santa Muerte in the crowd—ULA’s members also prepared two new themes for this year’s march. The first, positioned at the front of the parade, was group of Soldaderas or Rieleras, honoring the women fighters of the Mexican revolution. As marchers arrived, Vanesa Suarez and Fatima Rojas directed a stream of girls and women to a pile of bullet-studded sashes and wooden rifles, which they slung across their fronts like sashes, To complete the transformation, women had arrived in white blouses embroidered with flowers, and long skirts.

Rojas: It's revolution.

Rojas: It's revolution.

“The role women have played in war and revolution—they don’t get a lot of credit,” said Suarez, a volunteer with ULA who is finishing a degree in political science at Central Connecticut State University this December. “This year, women will lead the march.”

Rojas, meanwhile, fitted her daughter Ambar Santiago Rojas with a wooden rifle.

“You’re okay with the gun?” asked her friend and fellow Fair Havener Sarah Miller.

“It’s meant to show revolution,” said Rojas. She added that she saw a through line from 1910—the commencement of the Mexican Revolution—to today, with social protest. “We’re gonna be yelling, we’re gonna be making noise,” she said.

Friends Amy James and Ruthann Coyote pose against one side of the painted wall.

Friends Amy James and Ruthann Coyote pose against one side of the painted wall.

With that theme in mind, Suarez motioned over to a second new element this year: A two-sided “wall” that would be carried by marchers, comprising 10 large panels painted on both sides. On one, Suarez said ULA wanted to display “how the United States currently portrays immigration.” A pair of skeletal hands is joined by a pair of handcuffs, trapping an orange and purple butterfly as they try to break free. Further to the right, a dollar bill ripples, George Washington’s face replaced with a laughing, hollow-eyed skull. Beneath it, a long skeletal foot cuts into the frame.

Suarez said that the other side is meant to honor friends and family who have lost their lives seeking immigration to the United States. Several skeletons scale, behold, and try to jump over the wall, their fates on the other side unclear.

As marchers got their assignments, ULA volunteers and attendees from the community alike scrambled to finish their face designs. At a long table, Sylvie Borla put the finishing touches on her mom, Kathryn Foran: Bright, nearly dripping red lips and a heart in the middle of her forehead. Watching them nearby, Foran’s husband Steve Borla said that the family had made the pilgrimage from East Hartford for years. At the head of the table, organizer Jesus Morales Sanchez dabbed on another coat of white, pausing to take a selfie.

Then it was go time. Unrecognizable in a mask, ULA organizer John Lugo grabbed the mic and began to direct the parade, a sort of macabre ballet. People morphed into ghosts, hoisting up paper lanterns, giant decorated masks, vibrant Calaveras and banners. Members of the Hartford Hot Several gathered near the back, donning masks and checking the white lights strung onto their instruments.

Lined up on Mill and Saltonstall Streets, the march began slowly. Rojas trilled her tongue to send loud, ebullient sheiks into the air. Lurching slowly forward, the parade made its way down Saltonstall Street, a group of Mariachi strings near the front launching into “Cielito Lindo.”

“Ay, ay, ay, ay/Canta y no llores/Porque cantando se alegran/Cielito lindo, los corazones,” sang the Soldaderas, some hand-in-hand as they walked. Behind them, large skulls bobbed all the way down the street, turning gold in the day’s remaining light. A long dragon-like float carried by five people undulated as it came forward.

As the parade turned from Lloyd Street onto Wolcott, and Wolcott onto Ferry Street, families trickled out onto the sidewalk to watch. Some gathered on their porches, haloed in light, while others knew the group was coming, and filed onto corners with homemade masks and cheers to keep the paraders going. As dusk fell, the Hartford Hot Several’s Josh Michtom kept spirits high with a brass rendition of “Despacito,” complete with a staticy megaphone through which he sang.

“Ya, ya me está gustando más de lo normal /Todos mis sentidos van pidiendo más /Esto hay que tomarlo sin ningún apuro,” he belted. Three feet in front of him, Morales Sanchez danced in wild circles, his Calavera spinning against the sky.

The Hartford Hot Several’s Josh Michtom led the group in pieces that ranged from "When The Saints Go Marching In" to Jon Batiste and Stay Human's "I Feel Good."

The Hartford Hot Several’s Josh Michtom led the group in pieces that ranged from "When The Saints Go Marching In" to Jon Batiste and Stay Human's "I Feel Good."

When the music faded for a moment, someone near the back of the parade shouted “Whose streets?”

“Our streets!” the group bellowed back, switching back into Spanish as the Hartford Hot Several searched for more music. Soon, “When The Saints Go Marching In” was playing them down Grand Avenue. On the sidewalk, groups stopped what they were doing to watch.

Outside of a convenience store, 15-year-old DJ Daniels stopped his bike to take in the parade, not riding off until it had turned onto Blatchley Avenue. There with his friend James Malone, Daniels said he hadn’t known the parade was taking place, but was spellbound by the action in his backyard.

“It’s really cool to have this here,” he said. In the street, immigration lawyer Yasmin Rodriguez blew a large plastic horn, signifying that it was time for the parade to move forward.

As the group continued slowly down Clay, Poplar and Lombard Streets—marchers had to stop every few blocks for the wall to catch up—it gained members. Alexandra Taylor Mendez and her husband Chris Perralta joined in toward the back, estimating that this was the tenth year they’d attended.

Perralta recalled a parade several years ago, where even snow hadn’t deterred the marchers. There had been a freak snowstorm on a Saturday, freezing conditions for the parade. So the marchers “went rogue,” and did it the following day, still drawing spectators as they kept the route shorter, to one or two blocks. He said it’s been exciting to watch the route grow since, into a windy thing that takes over 90 minutes to complete.

“There’s nothing else in New Haven that really goes through the neighborhood like this,” he said. “Not down Dixwell Avenue, not down Chapel, but really through the neighborhood.”

As the parade streamed into Erector Square, marchers grew quiet for a moment, setting their Calaveras, floats and the wall on a cement loading-dock-turned-stage outside of Bregamos. Organizer Marco Castillo took the stage with Antonio Tizapa, whose son Jorge is one of the 43 students who went missing in Mexico three years ago. On Sunday, he was planning to run the New York City Marathon in honor of his son, with a green shirt that read “Running For Ayotzinapa 43.”

Amidst so much celebration, he said he had a request for attendees: Be vigilant, and contact your representatives to end The Mérida Initiative, which provides funds from the United States to Mexico’s security forces. Like the forces, Tizapa said, that are responsible for his son’s disappearance.

“I am and we are economically displaced from our country because we are in search of a better life for us,” he said in Spanish, Castillo translating. “The U.S. government is using your taxes to fund this war … one of the things that we want to ask you is to send letters to your representative or to the U.S. consulate in Mexico asking them to stop The Mérida Initiative. We’re counting on international solidarity.”

The audience cheered. Some members wiped away tears. A few posed for photos with Tizapa. Then they queued up to the door of Bregamos, where music, hundreds of hot empanadas, rice and beans and dancing was waiting inside. Remembering those who had come before them, they were ready to party in this world like the following day might be their last.