Greater New Haven | Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services (IRIS) | Refugees | Arts & Culture | New Haven | Visual Arts

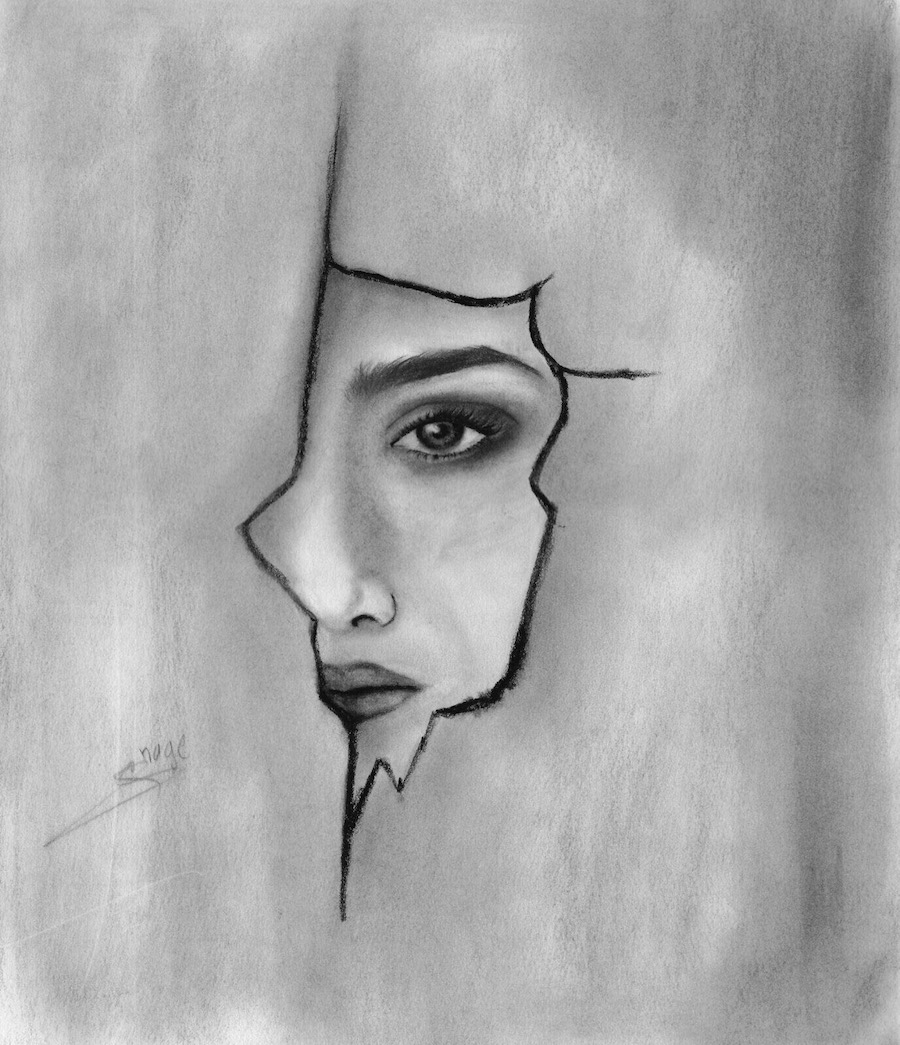

One of Raghida's works. Photo courtesy of the artist.

One of Raghida's works. Photo courtesy of the artist.

This article is the second in a two-part series we're running on what has changed for two refugee families, both of whom arrived on Election Day 2016, in the year since Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. A few of our readers have asked us why we don't have photographs of the refugee families. In both cases, it was their request that they not be photographed or identified by name. An earlier version of this piece appeared in the November print version of The Arts Paper.

Author Jake Halpern can remember getting into his car late at night, and driving through the darkness of New Haven with a chilled container of ice cream riding shotgun with him. It was the night before a predicted blizzard, and there were almost no cars left on the road. Halpern was in emergency mode: The refugee family he’d been working with for months had received a death threat earlier in the day, and now he and a translator were on their way to their home. Before ever committing it to paper—which he knew he would—he had to make sure that they were okay.

That experience has just been a small part of writing Welcome to the New World, a collaboration between Halpern, illustrator Michael Sloan and the New York Times Sunday magazine that follows two refugee families through their new life in Connecticut. Started as a commission from the New York Times, the series has now taken on a robust life of its own.

Jake Halpern. The Lavin Agency Photo.

Jake Halpern. The Lavin Agency Photo.

As the series turns one year old this fall, Halpern said he has found himself reflecting on what can happen in a year, and where the series—and its subjects—may go from here. On and off paper, that is.

Welcome to the New World begins with two brothers, their wives, and their families living in war-torn Syria, learning that they are going to be allowed emigrate to the United States. After an extensive vetting process, the families arrived in the U.S. on the evening on Election Day 2016. At the time, Democratic hopeful Hillary Clinton was still projected to win.

Halpern was part of the welcome team for those families when they touched down in Connecticut. By the next morning, Donald Trump had officially won the presidential election. Halpern’s world—and, he thought, the world of these very new Americans—was turned upside down.

“I realized … this family arrived in one country and woke up the next morning in another,” Halpern recalled in a recent interview. “And that became the lens through which I saw the whole thing.”

In crafting Welcome to the New World, Halpern chose to follow the two families, who were both resettled in Connecticut. Their names and specific places of residence have not been used here, although one is interviewed at length in a partner story on refugees and female entrepreneurship. One of the families is living in a smaller town and one is living in an urban area.

“The way our resettlement system is, you have just a few months to learn English, figure out how American society works, and get a job and be self-sufficient, which is kind of insane,” Halpern said.

Halpern saw that system observing the family in the city, whose story he chose to tell first. As he spoke to the family, Halpern learned that that the father—who he calls “Jamil” in the series—was tortured by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s security forces without cause. He’d sustained injuries to his back that made working nearly impossible. Jobs in HVAC (heating, ventilation, and air conditioning) fell through because of their physical demands, the tax they took on his body.

As Jamil struggled to find work because of his injuries, his wife “Oulah” emerged as a gifted cook. In their resourcefulness, she stepped up to run a small catering business, of which Jamil essentially became her manager.

It signaled a drastic change in the dynamics of the family. When Jamil, Oulah, and their children lived in Syria, Jamil was the breadwinner and Oulah stayed at home. Halpern said that the couple has since adjusted to what this means for them.

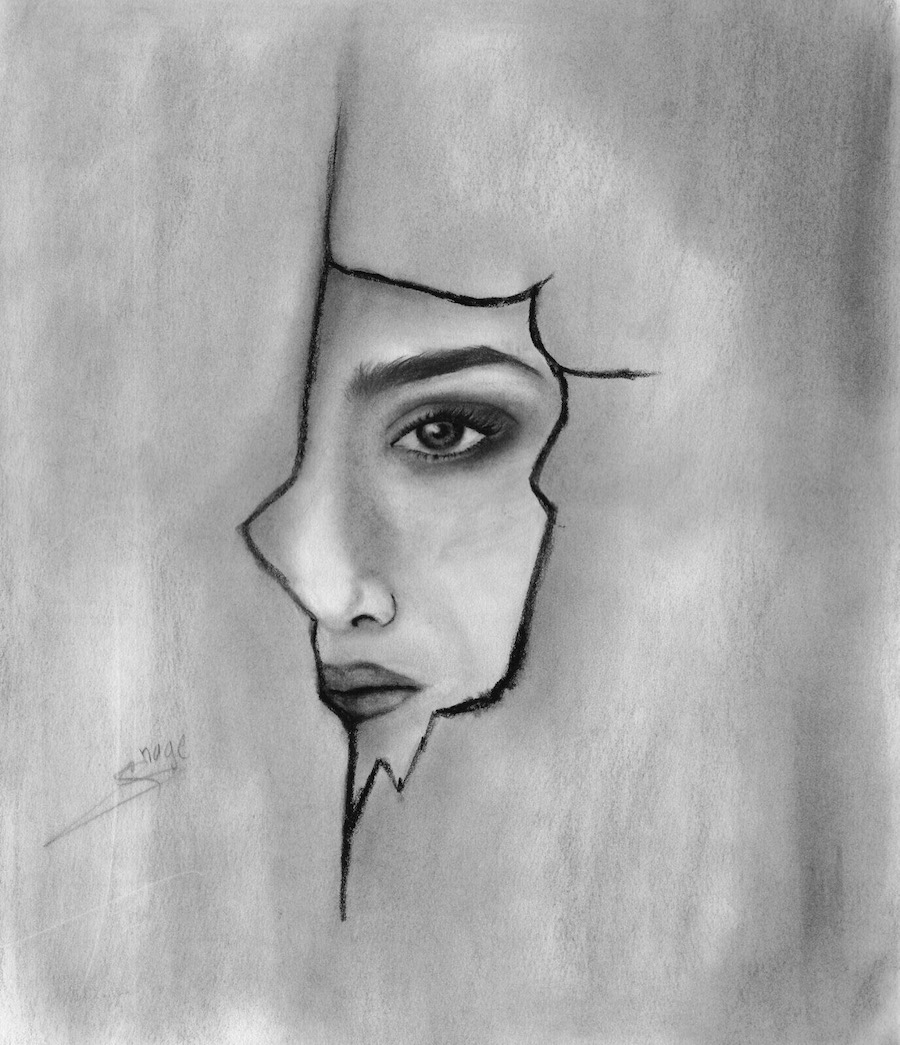

Raghida's drawing Sister. Courtesy of the artist.

Raghida's drawing Sister. Courtesy of the artist.

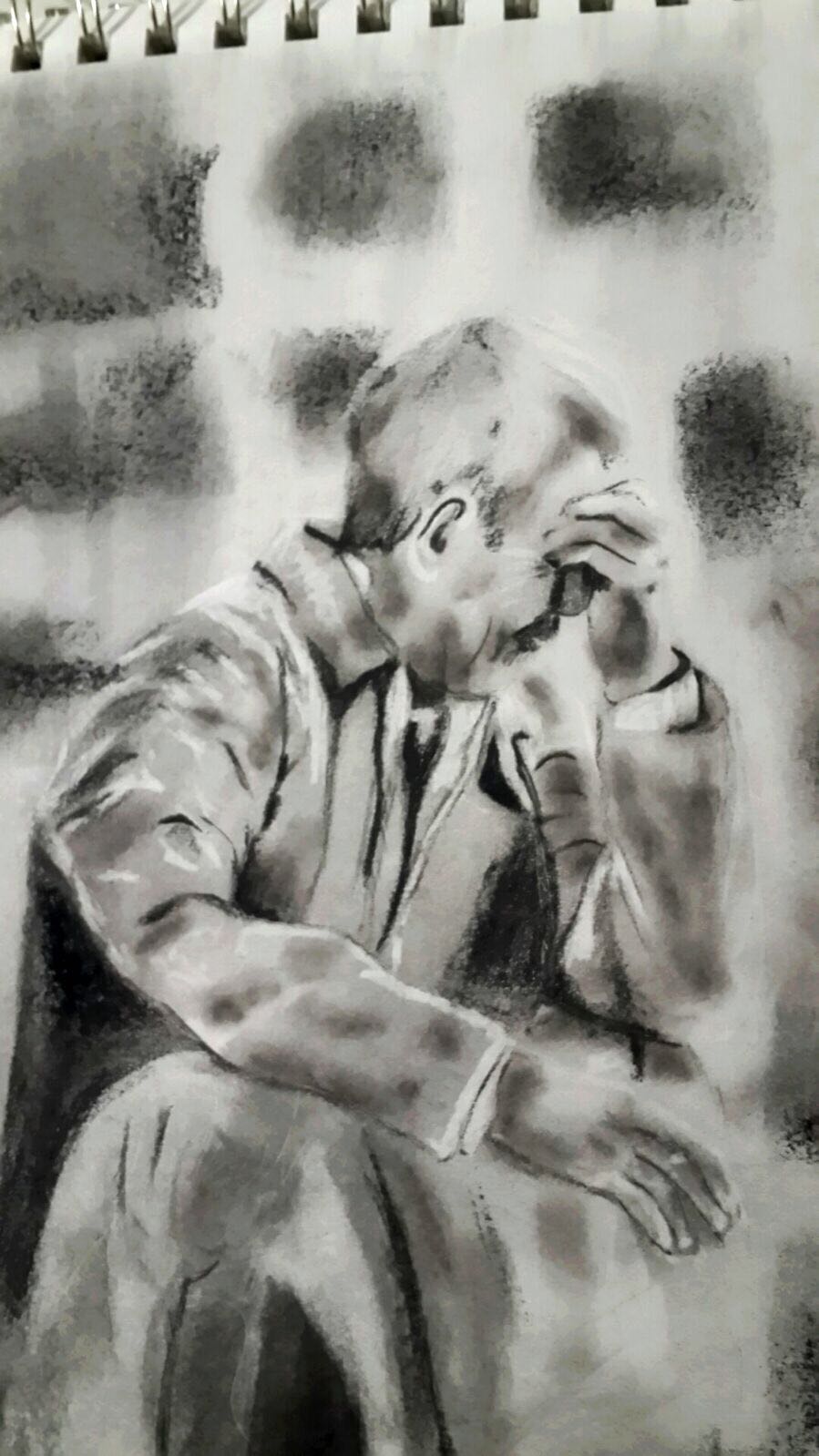

The other family—two parents, two teens, and three young kids—is living in small-town Connecticut compared to Oulah and Jamil’s family. But llike Oulah and Jamil, they have had a rough time settling into their new life.

First, they struggled to make friends in their community. Several months ago, the family received a death threat. In a recent interview, Halpern recalled that it was frightening because they had come from a part of the world where when you get a death threat, more often than not, someone ends up dead.

Not feeling safe, the family fled the town where they had settled, and resettled in a more affluent suburb of Connecticut. The father, “Ammar,” has a job in a factory where he's making what Halpern called a “decent wage.” His wife, “Raghida” is an artist has begun showing her work at local galleries and art shows.

While the family is still struggling to make new friends in their community, it is apparent to Halpern that they feel a sense of accomplishment despite the isolation.

“They have a car now, jobs, a house, and their children are excelling in school—all of which are benchmarks in American society for success,” he said. “I still think it feels like, it feels like ‘Oh my God, we're still strangers in a strange land.’ Being in the United States is far better than where they came from, for sure, and they're exceedingly grateful. But I think that doesn't mean that it's easy.”

When he is talking about the comic, Halpern is quick to point out that he didn't create Welcome to the New World alone. He credits Sloan with the vision to carry the comic through.

“I was immediately just blown away by his work,” Halpern said. “There was an element about his comics; the characters that he rendered were just kind of endearing and they had a familiar sense of warmth. The point of the comic was to make people feel—to make people realize that these are people kind of like us.”

“There's such warmth in some of the pictures,” he continued. “Like in the very first comic there's a moment where Jamil is leaving his apartment in Jordan, where he's been living, and he's talking to his bird because he collected birds and he said, ‘Sorry, my little friend you have to stay behind.’ It's just … this kind of avuncular, pudgy, slightly balding guy who's just like, has a fatherly smile and he's just saying goodbye to his pet bird, and Michael does it so tenderly, that drawing. That, in some way, said more than the words ever could.”

As the comic series comes to a close this year, Halpern is also reflecting back on what he has taken away from the experience. He recalled heading with one family to a mosque that looked like a converted clothing store, where “ they just cleared out floor space and this very small group of people get together to pray.”

“As a Jew, I felt [like] ‘Wow this is how my people lived through the vast span of kind of history, kind of on the fringes of society,’” he said of the experience. “I watched them pray, and I had this really strong moment of feeling that ‘this is me—this is my history, this is my connectedness.’ Then I realized that, of course, you wouldn't feel that way just as a Jew, you would feel that way as any small American ethnic group that arrived.”

A second thought came as Halpern heard that one of his own family members, on the opposite side of the political spectrum, had expressed disapproval at the series. Halpern’s family is "a family of Holocaust survivors,” and he was struck by the hypocrisy.

“It's ridiculous and I think that the problem is that basically you just have to meet someone … There’s a closeness in this project that has never existed in any other story that I've ever done,” he said.

Halpern and Sloan are working to move their comic into book form so that it can reach a wider audience. Meanwhile, the families themselves are also moving forward, finding the balance between the old and the new world.

“There's this hysteria about Islam but at various times it was focused on other people … the Chinese, the Irish, the Jews, Catholics, etcetera. It was always kind of like the rabble,” Halpern said. “I think those are the moments you somehow hope that you can convey to people that this is, this is the American story and, as corny as it sounds, that is true.”