The Disney brothers are having a fight about lemmings. According to Walt, who heard it from his production guy, who heard it from who knows where, lemmings are prone to commit mass suicide. It’s just something they do, hurling their little bodies into the ocean with a solid kirplunk.

Roy, the cautious brother, isn’t so sure. He wants to know more before going anywhere with the idea. But he’ll probably come up with a way to make it happen, if that’s what Walt wants. He always does. He’s his brother’s lemming.

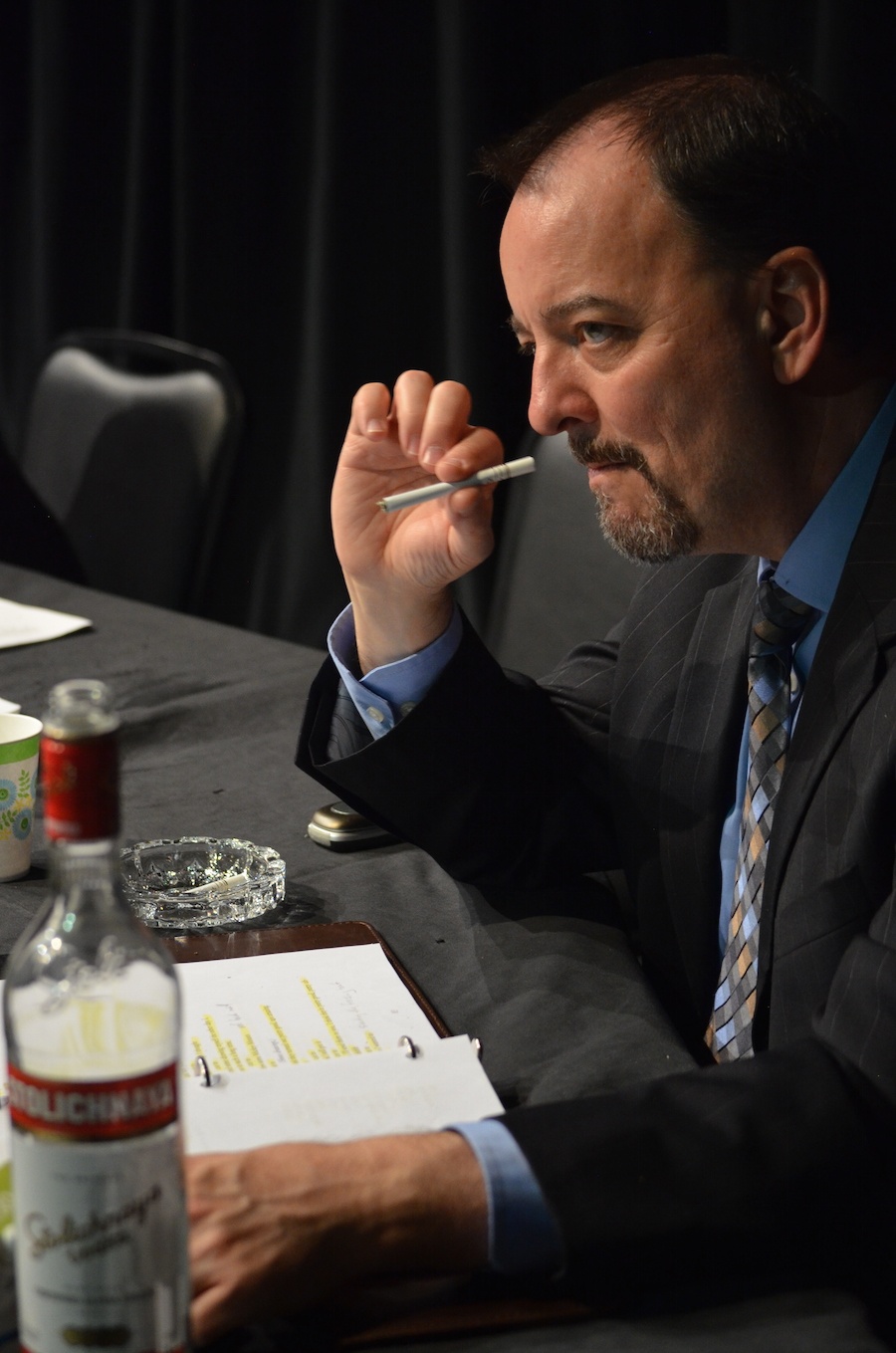

J. Kevin Smith as Walt Disney. NHTC Photo.

Such exchanges are par for the course in Lucas Hnath's A Public Reading of an Unproduced Screenplay About the Death of Walt Disney, the 2017-18 season opener from the New Haven Theater Company (NHTC). Directed by Drew Gray, the play runs now through Nov. 18 at EBM Vintage on Chapel Street. Additional ticket information is available here.

Written in 2013, the play is a recent take on the late life and death of Walt Disney, the man we love to love, then love to hate over time. This is the anti-Saving Mr. Banks, a snappy and dizzying narrative that explores Disney as an intolerable bully, a tyrant whose role as human cancer finally takes him with it. Decidedly un-jolly, this Walt Disney is exhausted and exhaustible, churlish, and infantile, prone to tantrums at the slightest sign of things not going his way.

It's timely, for sure. As Walt speeds through his opening lines ("Fade in. Fade in on me,/Walt, fade in on Walt, fade in on Walt./Walt. Close on Walt./Walt is good./Walt is doing good, looking good, looking good for his age,/age or no age looking good. Walt is/quick and smart and sharp and great."), we can imagine another menace at his keyboard, ready to throw a Twitter fit about his grandeur and importance. But it's also a strange, fantastical and imaginative take on Disney the tyrant, putting truths and untruths beside each other to squirm uncomfortably. True to its name, the play is produced as a largely flat reading, taking some liberties that keep the viewer hooked.

In EBM Vintage’s small blackbox theater, that world springs to life. Against a wall plastered with instructional diagrams on Mickey Mouse, we are introduced to an unkempt Disney (a pitch-perfect J. Kevin Smith), who keeps tiny figurines of Mickey, Minnie and Donald Duck beside his pills and vodka. Even before he comes onstage with his staccato mustache and half-frown, we know something isn’t right. A large, animated Mickey is splattered with blood on the back wall, and Disney is missing in action as music crackles over the set. Characters are quiet and tense, their act of waiting (itself an act) funny and strange in an uncomfortable sort of way.

Once he arrives, things don’t get much better. They’re not supposed to. Switching from one side of the reading to the other, Disney exchanges rapid-fire dialogue with his brother Roy (Steve Scarpa), daughter (Melissa Smith) and son-in-law Ron (Trevor Williams), proclaiming “cut to” as a sort of jumbly, frenetic time-jump every few lines. With it, the group hurdles ahead, time not on their side as Walt maniacally directs them.

As Disney, Smith is dynamite. From the moment he walks onstage with a dour expression and pockets packed with blood-tinged tissues (it is the mid 1960s, and he’s well on his way to being dead from lung cancer), he is Walt Disney, who is not a very likable character. His sense of the script’s lightning-fast timing and dulled affect is right on. In one interaction, he needles his brother Roy into taking blame for an error that was his. In another, he and Ron wax poetic on the virtues of being a bully. In a third, he lists off a laundry list of fans that include Eisenstein, Einstein and Mussolini, just in case he hasn’t made your skin crawl yet.

What stands out are the Hnathian twists that turn the tidy Walt Disney biopic story on its head. In the script, Hnath has instructed actors to read through their lines as quickly and cleanly as possible, with the additional note to “Avoid trying to play ‘emotion’ of the lines. Inflection takes time, and you don’t have that much time.” In his hands, Disney is playing a game of human battleship, and every line is another set of possible coordinates.

It destroys, quickly and not without humor, the mythology of Walt Disney. Here is a man who has managed to outlive death with his movie spinoffs and manufactured, bubble-like fantasy worlds in Orlando, Anaheim, Paris, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Tokyo. A man who, in Hnath's universe, has so much faith in the power of his mind that he will do anything to preserve it. A man who becomes Mr. Alternative Fact, because he cannot deal with a world in which he might be wrong.

It's here, fittingly, that the play ends with stunning but quiet momentum. Disney has finally lost his head—literally—and what exists is his obsession with legacy, cold as the freon that Hnath has running through his veins. It's an ending for Walt that we've never seen before. And yet one, it seems, that we've heard somewhere before.

and Walt is happy

and Walt is loved

and Walt is happier than he’s been

better than he’s ever been

smarter than he’s been

and everyone misses him.