Soto advocates for Yale University to become a sanctuary campus at a protest last year. Paul Bass for the New Haven Independent.

Throughout the month of December, The Arts Paper will be doing some follow-up stories on artists we’ve met and covered since our digital launch in August. Here we catch up with Juancarlos Soto, a community organizer and activist who blends his love of politics and visual art. Back in September, he was just thinking about a series that took on Trump's DACA rollback. Now, it’s a living and breathing thing—and it comes with more subject matter than he thought it would at the time.

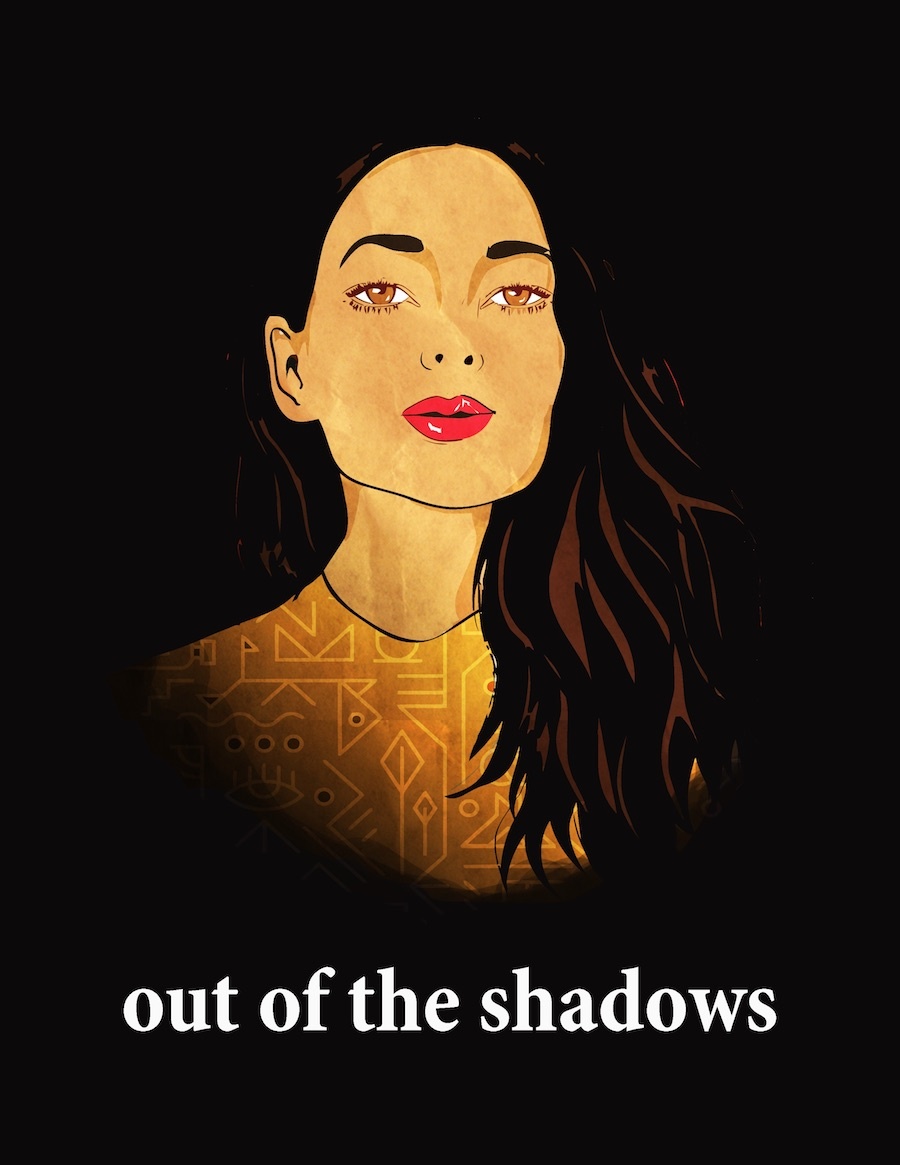

New Haven Artivist Juancarlos Soto has followed through with his promise to merge anti-Trump protest and visual art in new prints. Now, he’s working to get them out into the world—and using them to reorient the conversation around women of color leading the resistance.

Image credit Juancarlos Soto.

That’s Soto’s hope for his newest body of work, focused on DACA recipients, Black and Latina women, and the Me Too movement that has swept across the country in the past two months. A community organizer with Planned Parenthood of Southern New England and Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA), Soto has been working toward the pieces for months, as he follows news of both Trump’s move to end Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and women coming forward with allegations of sexual harassment and assault.

The idea for the pieces began in early September, when Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that they planed to end DACA, leaving 800,000 youth at risk of deportation. Soto snapped to attention, protesting at Trump Tower in New York and organizing at home in New Haven. He watched as U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro called for a “clean” DREAM act for those recipients, and as Trump continued to fight Democratic legislators on the measure.

A month later, he watched as thousands of women started posting #MeToo status updates on Twitter and Facebook. At the time, the trend was ascribed to actress Alyssa Milano, who tweeted out “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote ‘Me too’ as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.”

Soto said he knew that it wasn’t exactly the case: #MeToo is a movement that goes back 10 years, to sexual assault survivor Tarana Burke, who has called healing a radical act in itself. He saw in the movement a troubling and common trend: something started by strong women of color had been coopted by white women, who were able to break their silence on the subject without the same amount of doubt and stigma.

“It made me furious because it happens so often in our movements,” Soto recalled in an interview Thursday, one day after marching in Hartford for a national day for immigrant rights. “People have been fighting for some time, and someone comes along and picks up credit.”

That, Soto realized, was where he had to go with the series—a place where his hopes for the safety and wellbeing of DACA recipients met his respect for many of the women leading marches, rallies, protests and actions across the country. Not only respect, he said, but an acknowledgement of their place at the helm of these movements, where they have always been.

Image credit Juancarlos Soto.

"Art is my go-to to be able to process a lot with what’s going on," he said.

Images began to materialize in his head. In one, a woman’s face emerged from the dark abyss behind her, with the declaration that she was out of the shadows, and not going back. Her lips parted and glowed with bright color, her eyes blazed. Her hair cascaded over her shoulders, falling onto a chest emblazoned with clean, sharp symbols. He began to commit the designs to paper.

In another, Burke—or perhaps not Burke, but the millions of women that Burke has inspired—stands dead center, locking eyes with her viewer. Her fro frames her face, eyebrows arched, pupils dilated, whites of her eyes unflinching. Her arms are crossed, lips pursed in a sort of beautiful standoff. She wears a simple white t-shirt, emblazoned with the words #METOO in a deep pink that is almost red. Her shoulders are angled but out, and comfortable right where they are. She is not going anywhere.

In both, “her face tells you that you’re not going to push her back into the shadows,” Soto said. “Which I think is the spirit of young folk and the 11 million [undocumented migrants] that are being told that they’re too Brown or to Black or too queer or too Muslim to be here.”

“I was capturing the spirit pf this young, strong woman," he added of the #MeToo piece. "To me, she’s sort of the opposite of these older white men who had a lot of money and influence. She’s very secure, very defiant, able to stand up for herself. Even down to the way she’s dressed … I kept seeing all these men in suits. So I put her in a t-shirt. I tried to the best of my ability to make her graceful still.”

There was never any doubt that he would depict women, he said. "In my mind, there’s so much of that male, destructive energy being pushed around in D.C. ... I also think that there’s a lack of our representation of women of color in art. I have four nieces, and I want them to be able to see art that looks like them.”

But he doesn't feel finished, he said. What stated as a therapeutic project for him so many years ago is now his form of after-hours community building, when he’s taken off one organizing hat to put on another.

“As an artist, it’s cool that people are connecting with your art,” he said. “But as a community organizer, it’s really cool to know that my art is helping people build power within themselves. It feels like I’m bringing some love and some positivity into the world in a really cool, lasting way.”

To find out more about Soto's work or to buy a print, visit his website.