Photography | Arts & Culture | Artspace | New Haven | Visual Arts | Yale University Art Gallery

Jim Goldberg, US-1 , 2014. Archival pigment print. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Jim Goldberg, US-1 , 2014. Archival pigment print. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Maybe it’s the woman’s unkempt, copper-colored hair that catches you first, or the sun-ravaged mole above her right eye. Maybe it’s the not-quite-white shirt, slipped over her small breasts and torso. Or the hint — and it is the smallest of hints — of a smile below two deep wells of exhaustion, and eyes that look just past the frame.

If you don’t know New Haven, there’s no reason to believe the apocalypse hasn’t happened. The building behind her is shuttered, with a green awning that looks like it has seen better days. The lot behind her boasts cracks and potholes in the asphalt, a telephone pole with wood that’s become three different colors. There’s trash and overgrown grass everywhere.

But it’s not the apocalypse. It’s the intersection of Ella T. Grasso Boulevard and Columbus Avenue where the city is weighing improvements to one of its oldest bus stops.

Therein lies the struggle with Candy/A Good And Spacious Land, on view at the Yale University Art Gallery (YUAG) through Aug. 20. Hidden in the museum’s quiet fourth-floor study gallery, the exhibition paints New Haven as a largely flailing city, the victim of an urban renewal that wasn’t. It is one of two exhibitions this summer to explore the city’s identity; the other, Masturbatory Delusions, is on at Artspace through Sept. 9.

Jim Goldberg, Whiffenpoofs, Mory’s Private Club , 2013. Archival pigment print. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Jim Goldberg, Whiffenpoofs, Mory’s Private Club , 2013. Archival pigment print. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

The culmination of a two-year residency at YUAG, Candy/A Good And Spacious Land comprises the photographs of Jim Goldberg and Donovan Wylie, who have published eponymous volumes with the gallery. With text from Christopher Klatell and Laura Wexler, the books are quite beautiful. Goldberg documents his childhood in the city, covering two stages of urban renewal, Mayor Richard C. Lee’s love affair with development and its discontents, and ultimately his departure from a decidedly non-model “Model City.” Several of his street photographs are shot from the top of a moving van, giving the viewer an elevated, drive-by view of the city and the people who fill it.

As a counterweight, Irish-born Wylie seems obsessed with the idea of propulsion, zeroing in on the city’s marriage of interstates 91 and 95 with its recently completed Q Bridge Project. Large, sturdily composed photographs beckon with with images of the construction, filling the frame with temples of cement and tar, snapshots of workplaces that will not outlast construction. Almost every photograph features a low-hanging gray sky, as though the highway might get to heaven if built high enough.

Donovan Wylie, New Haven, Connecticut , 2013. Photograph. © 2017 Donovan Wylie

Donovan Wylie, New Haven, Connecticut , 2013. Photograph. © 2017 Donovan Wylie

It’s a captivating thesis: two artists peering in from outside, trying to parse out the city’s past and present. One returning, one stranger, in dialogue through their work.

But the exhibition is more bitter than sweet. Steeped in Goldberg’s nostalgia and Wylie’s assumption, it depicts a New Haven that can’t shake its rough and tired exterior, a city that’s only as good as its bleak national reputation.

Wylie, from the first image, doesn’t dig deep (which is inherently funny, in photographs dedicated to a massive transit project). The photographs are stunning, and incredibly satisfying in their composition — but they don’t tell the full story of the Q Bridge Project, the result of a TIGER grant from the U.S. Department of Transportation.

What Wylie gets right is that the $600 million project felt unending, and was an arduous, detour-creating mess that looked like a series of roads to nowhere for a while.

But absent are the weekends that the department opened the project to the city’s public, leading tours of its progress, creating partner exhibitions on transit in New Haven, and inviting local artists like Michael Angelis to document a region as it changed before his eyes.

Donovan Wylie, New Haven, Connecticu t, 2013. Photograph. © 2017 Donovan Wylie

Donovan Wylie, New Haven, Connecticu t, 2013. Photograph. © 2017 Donovan Wylie

Goldberg, meanwhile, doesn’t move beyond his hangups with urban renewal and its fallout. There is nothing to celebrate here, he says of the streets of Dixwell, Dwight, Fair Haven, the Hill and even New Haven Green. I’ve packed up, and maybe you should too. On a scroll of photographs that visitors are encouraged to work through, New Haveners and their homes freeze mid-frame, caught in the shaky and elevated camera work of a street photographer who doesn’t want to know the streets he’s on.

It’s not inaccurate, just wildly incomplete. Cutting through the city like a scar, I-91 has wrought damage on New Haven, chewing up the city and leaving segregated, piecemeal neighborhoods in its wake. The absence of bodies in several photographs isn’t forced: it’s true that certain areas aren’t pedestrian-friendly, and don’t invite long postprandial walks or scenic sunrise jogs. But it’s not the full story. Not even a chapter of it.

Donovan Wylie, New Haven, Connecticut , 2013. Photograph. © 2017 Donovan Wylie

Donovan Wylie, New Haven, Connecticut , 2013. Photograph. © 2017 Donovan Wylie

Take Goldberg’s US-I (pictured at top), the photograph that has been used on almost all of the exhibition’s promotional material. Our weathered, copper-haired heroine looks like she’s been transported from Cormac McCarthy’s post-apocalyptic The Road to the middle of the city, the only human left out there.

The reality is perhaps less dramatic: she’s probably catching the bus. The B, to be exact, which picks up every 20 minutes at the intersection of routes 1 and 10 and trundles down Congress Avenue toward downtown New Haven. It’s one of the first stops in the city, where West Haven becomes New Haven.

Goldberg’s eye is right on at first: She’d be one of only three or four people to use the stop each hour, and would be paying for the bus only if a car were too expensive.

But inside, all bets on the city’s bleakness, its unending poverty and hers, are off. Say she gets on. Maybe she’ll watch two mothers trade advice as they breastfeed in the front seats. Or pass Ring One Boxing Gym, with its swooping gold letters and impromptu gathering of teens outside. On the left, she’ll pass Krikko’s Hill Museum on West Street, and then the quirky majesty of Deliverance Temple Church and the new John C. Daniels School. If she takes it to the Green, she might end her trip there, or get on the J bus, a frequent transfer from the B.

Of course, we don’t know this. We don’t know anything about her at all, except that she is so tired, weathered and ashamed she can't quite look at the camera. We don’t have much of a say in her narrative, and she doesn’t either.

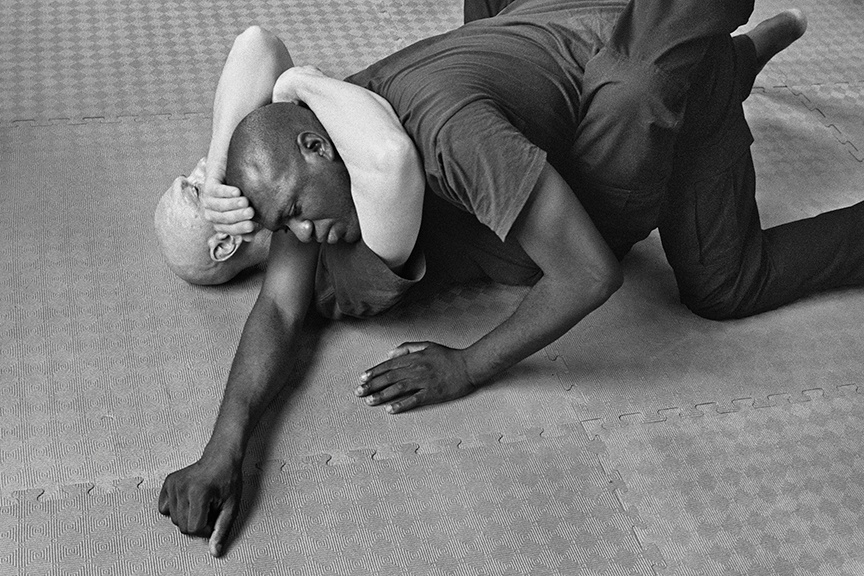

Jim Goldberg, Training Day, New Haven Police Academy , 2014. Archival pigment print. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Jim Goldberg, Training Day, New Haven Police Academy , 2014. Archival pigment print. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

The majority of Goldberg’s photographs halt at this perception that the city, perhaps like the world he inhabits, is flat. On one side of the gallery, defeated 2013 mayoral candidate Justin Elicker stands against a wall, eyes downcast, skin ashen next to the deep blue of his jacket. Gone is the fiery alder who fought for transparency from a Cedar Hill factory, and rallied for his constituents when it didn’t tighten safety regulations fast enough. The man who, in the year following the photograph, was capable of delivering a child at home, revitalizing a city nonprofit, and testifying on behalf of his neighborhood at zoning meetings.

On another, a polaroid of then-Lt. Holly Wasilewski (she is now Community Outreach Coordinator at the U.S. Attorney’s Office downtown) winks out from a panel with the words It’s not always easy being a female police officer./But I love my job. With her blonde hair tied back, she looks out onto the road, her patrol gear across her front like some odd, militant sort of sash. You’d never know that this was the cop who talked down robbers holed in a Davenport Avenue apartment before a SWAT team had to get involved, or an enthusiastic participant in neighborhood Easter celebrations, saver of cats, negotiator of negotiators.

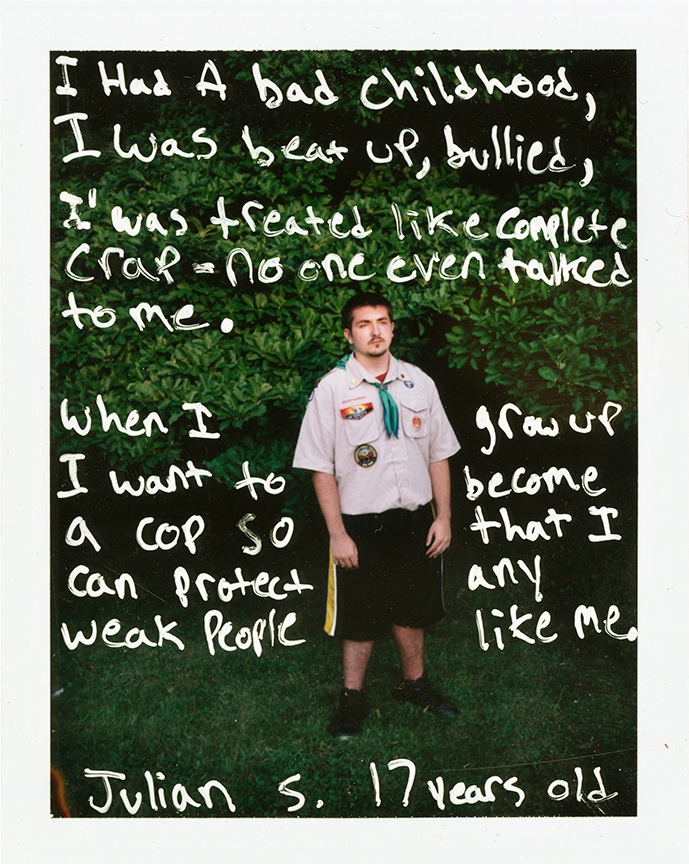

Jim Goldberg, Julian S. , 2014. Internal dye-diffusion transfer print with ink. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Jim Goldberg, Julian S. , 2014. Internal dye-diffusion transfer print with ink. © 2017 Jim Goldberg. Courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York, and Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco

Most everywhere, the walls burst with these stories. Most everywhere, they are muted. It’s especially true for Goldberg’s black and Latino subjects, who either appear pugnacious in the camera’s hungry lens or slink away from it, covering their faces with hands out, fingers extended.

In low, almost sepia tones, Mayor Toni Harp looks exhausted and filled with bloat, overwhelmed by a city that’s getting away from her.

This is not a show on vibrancy and forward progress. It’s a story of a city that lacks both heart and heartbeat. A city that New Haven may have been at one point, but isn’t right now, and is working hard not to be. It’s unclear who this show is for — maybe Goldberg, an exercise in closure and catharsis — but it’s certainly not for those who believe that there is good here, on every city street.

Unwittingly, it’s also a conversation piece with Masturbatory Delusions, which lives a 15-minute walk down Chapel Street and hard right onto Orange, in the city’s Ninth Square neighborhood. There, close to 50 photographs by the city’s high school students are on view at Artspace through Sept. 9.

Anthony Irizarry, Metamorphosis Series. Artspace Photo.

Anthony Irizarry, Metamorphosis Series. Artspace Photo.

With a title from James Baldwin’s 1972 No Name in the Street, the exhibition tells a wildly different story of New Haven. Taken by 18 young “photo warriors” during the organization’s Summer Apprentice Program (SAP) with photographer Nona Faustine, the photographs are full of light and life, navigating the complexity, frustration, and joy of living in New Haven at this moment. Come with us, they say, and we’ll show you around.

From start to finish, the exhibition is exhilarating, crackling with family histories, self-interrogations and intrepid questions. Early on, we find ourselves face-to-face with one of the city’s youth, watching Anthony Irizarry's discover himself. In his outstanding Metamorphosis series, a young artist grapples with the bounds of gender, swaying in a curly black wig in one still and posing as male in the next.

Michael Jonathan Jimenez artwork. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Michael Jonathan Jimenez artwork. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Two walls past him, Metropolitan Business Academy student Michael Jonathan Jimenez sits at a table waving miniature american flags. Thousands Pass Kennedy’s Bier, the paper reads. On a wall across the room, fresh photographs from protests for Nury Chavarria find new relevance in Marco Antonio Reyes Alvarez’s refuge at First & Summerfield Church.

Some are wonderfully intimate and vulnerable; others pose massive questions using local landmarks . Depicting a face obscured by a wet American flag, Benie N’Sumbu’s nation-straddling Between the Two probes what it even means to be from a place, and to embrace a new one.

Benie N'Sumbu, Between the Two Series. Artspace Photo.

Benie N'Sumbu, Between the Two Series. Artspace Photo.

Phoenix Taylor’s Courthouse, meanwhile, asks how long it might take to feel un-small in the face of a large and centuries-old legislative body. Warping perspective, a miniature figure shot at an angle stands before the courthouse, shoulders squared. She is asking, it seems, if the arc of justice might ever bend in her favor.

The central question they all pose — not unlike one present in Candy/A Good And Spacious Land — is who gets to write New Haven’s history? The white men who have always tried to write it, or the city’s majority-minority youth and their families? Who controls this narrative, and what does it mean to speak (or rather, picture) truth to power?

“You know, life is a learning experience,” said Faustine at the show’s recent opening. “My mother always said, never stop learning. And the day you do, you’re ready to leave this earth.”

Her warriors have taken up the advice. Drawing from rich traditions of Gordon Parks, Carrie Mae Weems, John Pinderhughes, Ruddy Roye and others, they show the city as it is — imperfect and evolving, poverty-stricken and revolutionary, extraordinarily hopeful and innovative in the face of adversity.

These capture a scrappy, diverse, celebrated sanctuary. As if to say, welcome to New Haven. As if to say, hello, what would you like to know about my city?