Culture & Community | Religion & Spirituality | Reporting from the road | Solar eclipse | New Haven

NASA Photo

NASA Photo

Christoph Whitbeck guided his raft toward a Tennessee riverbank. Sarah Miller sprawled out on a blanket in a Kentucky field, huddling close to her husband and young sons. Kerry Brown made sure her three boys were wearing the right eyewear as she rolled from New Haven into small-town Tennessee. Amy Durbin lined up deck chairs with her aunt just short of the North Carolina-Tennessee state line. In the car with his brother, Lior Trestman raced the clock.

I was in South Carolina, waiting for 2:41 p.m. to hit.

We were just a few of New Haven’s “shadow chasers” who made our way by car, plane, foot, and whitewater raft into the path of totality Monday afternoon. Each propelled by the allure of a total solar eclipse, we headed south, crossed our fingers for clear weather, and turned our eyes cautiously toward the sky.

A school group looks on as the eclipse begins in Columbia, South Carolina. Lucy Gellman Photo.

A school group looks on as the eclipse begins in Columbia, South Carolina. Lucy Gellman Photo.

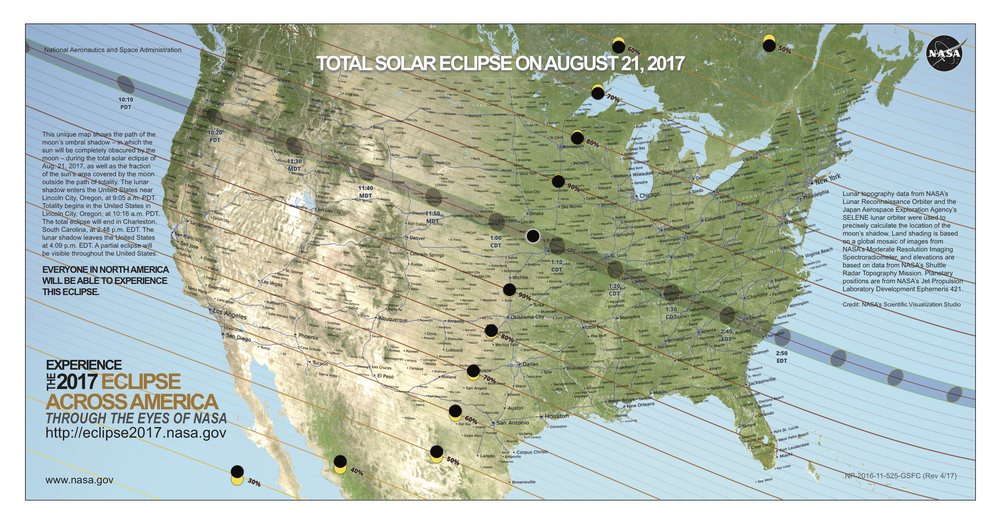

While there have been both total and annular solar eclipses in the last century, Monday’s was the first to travel coast to coast in almost 100 years. According to maps by The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), the moon's shadow came into the country in Oregon, traveling on a downward diagonal across the continental United States.

From Oregon, it raced across Idaho, Wyoming, Nebraska and Missouri, ultimately hitting Kentucky, Tennessee and the Carolinas before exiting the country around Charleston. With the moon’s shadow moving at 1500 to 2500 miles per hour, the moment of totality lasted only about two and a half minutes.

Partial eclipses, meanwhile, were visible across the country. According to NASA estimates, New Haven came in at between 60 and 70 percent visibility.

For many in the Elm City Monday, that was sufficient reason to nerd out for part of the afternoon. But a few intrepid New Haveners clocked the extra miles to see the totality firsthand.

One of them was Kerry Brown, a social worker at Yale-New Haven Hospital who hadn’t been planning to take a trip until she and her husband Pat saw a special eclipse spread in the New York Times a few weeks ago.

The two “felt like it was too amazing an opportunity to pass up,” she said in a text message Monday afternoon. She said their vacation time was extremely limited, so they did the only thing that worked with their schedules: pack up their three boys in the car, and head to Tennessee over the weekend. The five rolled into Knoxville at 1 a.m. Sunday morning, tired but happy.

The Browns get in position. Kerry Brown Photo.

The Browns get in position. Kerry Brown Photo.

Then, Brown recalled, a sort of pre-eclipse magic started happening. Out in the foothills of the Smoky Mountains, the family found at nonprofit that was hosting an eclipse party for residents of the area and visitors alike. There was a pool, and her boys mastered the ropes of gagaball, a kind of dodgeball. Then on Monday, they assembled for the big event, and donned their eyewear as a family.

As the sky shifted from blue to gray to black, the five “jumped up and down, asking each other if we were really seeing what we were seeing.” Around them, the area grew dark enough for a streetlight to spring on. Then, just minutes later, it was over.

“Seeing this black hole with a halo, where the sun was supposed to be, just blew us all away — totally worth it!” she wrote. “The total eclipse was unlike anything I could ever show my kids.”

“Despite insane traffic and exhaustion and everything else inherent in driving three kids 1600 miles round trip in about 72 hours, we’d do it again in a second!” she added.

They’ll have a chance too — the next eclipse is in 2024, and Brown said they’re already planning to make time to see it.

The lunar limbs known as "Baily's Beads," visible during eclipses. Reinhold Wittich Photo for the American Astronomical Society (AAS). With use through Creative Commons.

The lunar limbs known as "Baily's Beads," visible during eclipses. Reinhold Wittich Photo for the American Astronomical Society (AAS). With use through Creative Commons.

Miles away in Ocoee, Tenn., Christoph Whitbeck and his girlfriend Kimmie Johnson were having a very different eclipse experience, watching it unfold beside a thunderous river that they’d been braving all day.

They’d ended up there after reading about the eclipse earlier in the year, and deciding to head to Johnson’s native Knoxville for the totality.

With New Haven friends Micki Impellizeri and John Melien, they’d added another leg: an eclipse-specific whitewater rafting trip, led by a company called Adventures Unlimited. With 10 other rafts, they headed towards the moment of totality, oars ready and dripping and spirits high.

Except, not high enough to watch the eclipse on the water. As the eclipse began, Whitbeck learned how to sit on his raft a certain way, not looking directly into the sun.

As the totality grew closer, members of Adventures Unlimited had the group place its rafts on the riverbank, where participants set up shop for a short while. That’s where Whitbeck was when the moon edged itself in front of the sun. Only a golden corona, or halo, peeked out.

“It was rad,” he said by phone Monday evening.

Durbin Family Photo.

Durbin Family Photo.

On the very edge of the Cherokee National Forest in North Carolina, New Havener Amy Durbin gathered with eight members of her family, corralling two young cousins on the porch of a family vacation home. As the two of them clamored for ice cream and bounced around the porch, her mom presented the four year old with an eclipse gift: protective eyewear that came with a journal, where members of the group could commit their observations to paper as they waited for the moment of totality.

The director of education and visitor experience at the New Haven Museum, Durbin said she listened with delight as her aunt wrote down familial observations from the day. As the moon’s shadow encroached on the sun, she mused that it looked a little like the yellow arc at a McDonald’s restaurant. It went in the journal.

“It was really cool for us,” she said. “The fact that it’s constantly changing over an hour … and now we have our memories [of the eclipse].”

At her stakeout in Boone — and other locations in the south — watching the whole eclipse (pre- and post-totality) spanned about two hours. While the youngest members of the family weren’t entranced for that long, she stuck around for it, and used it to reflect on everything taking place in the country right now.

“In the wake of recent events, I think this is a positive experience bringing together people across the country,” said Durbin, who is from Charlottesville. “I think that’s the best part.”

Cruz, with Pablo and Mateo. Sarah Miller Photo.

Cruz, with Pablo and Mateo. Sarah Miller Photo.

That was also true for Sarah Miller, who’d committed to doing the trip in June. Her husband, Lee Cruz, had made a convincing pitch — he’d seen one in Nicaragua in 1991, and remembered it as a transformative experience.

Hopkinsville becomes "Eclipseville."

Hopkinsville becomes "Eclipseville."

With their young sons Pablo and Mateo, Miller and Cruz had been prepping for the eclipse with videos and podcasts for weeks. Then on Friday, they hopped in the car, and headed to Kentucky. With stops built in along the way, the trip took them the better part of two and a half days. On Sunday, they rolled into a small town called Hopkinsville — just in time to discover that it knew how to prepare for a total eclipse.

For the long weekend, Hopkinsville wasn’t Hopkinsville anymore. It was Eclipseville, with an athletic-field-turned-campground and eclipse-themed activities at a local community college. From preparations for the eclipse to Pablo's visit with a former astronaut, she said the experience wildly exceeded her expectations.

“There was so much hype, and I don’t get floored very easily,” she said via phone Monday night. “But it was very dramatic — much more than I thought it would be.

“You think that there aren’t that many new experiences to be had in the world, but this is the one,” she added. “We loved being able to look down in the field and look up. I wish that it lasted longer.”

Commemorative goggles, handed out at the museum.

Commemorative goggles, handed out at the museum.

I did too, ultimately. In Columbia, South Carolina, I stood outside of the South Carolina State Museum, sweating through my clothes and listening to a nearby group of boys joke about “moon babies” — babies conceived during the eclipse’s two and a half minutes of totality. I had traveled there to be with my boyfriend’s family for the eclipse, certainly not to make any moon babies, and wasn’t fully convinced that it would live up to hype either.

Christopher Breen takes in the tree-turned-camera-obscura. Mark Byrnes Photo.

Christopher Breen takes in the tree-turned-camera-obscura. Mark Byrnes Photo.

I’d seen the commemorative T-shirts, posters, and eclipse-themed Italian Ice flavors (chocolate with Oreo chunks, if you were wondering). But it was almost 2 p.m., and the sun still beat down on us, a wave of humidity traveling across the parking lot. A few yards away, a large school group clad in shorts and navy blue shirts looked up at the sky, students tugging at their faces to check goggle placement. For a while, nothing seemed to be happening.

Then, slowly, the sky began to darken, as if in a gentle thunderstorm. A few trees in the parking lot created impromptu cameras obscura, projecting tiny crescents onto the white parking strips. Even in still-bright sunlight, cicadas began to chirp, first faintly, and then loudly, unsure of what was going on. Their song lulled for a little while, then started back up.

It was 2:39 when the sky went from blue to grey to black. The campers cheered. The cicadas kept freaking out, their near-mechanized sound rising still. Cries of “totality!” went up from the crowd, with nondescript woots and yooooooous following. For two and a half minutes, eyes were glued to the sky as planets winked out, and pinks and blues came across the horizon line.

Then just as quickly, a diamond of bright sunlight reappeared, and so did our shadows on the ground.

Little did I know, a fellow Elm Citizen was racing into the path of totality not far from me.

Trestman, with his homemade glasses. "It should go without saying that I absolutely would not recommend making your own glasses, and I can't say for certain that our retinas escaped any harm," he wrote after the fact. Lior Trestman Photo.

Trestman, with his homemade glasses. "It should go without saying that I absolutely would not recommend making your own glasses, and I can't say for certain that our retinas escaped any harm," he wrote after the fact. Lior Trestman Photo.

Sunday night, Lior Trestman had rented a car, picked up his brother and started the journey from Connecticut to Virginia, where his dad lives. As he drove, he tasked his brother with finding glasses for the eclipse. After “at least a dozen” stores said they were out, the two decided to make their own, with two pairs of UV filtering sunglasses and paint tray liners made of a black film plastic.

They also decided to make pit stops in the south: first at a shooting range, and then a barbecue joint. Such that when the eclipse began, they were three hours behind schedule — and debated where to stop to watch the eclipse. "We and half the country raced for the swath of totality," he said.

Lior advocated stopping to watch the whole process. His brother urged them to drive further into the path of the moon’s shadow before the moment of totality. Ultimately, they took the second option, finding a friendly farmer who let them sit atop his hill.

“It was like the dimmer on the world was just slowly being turned off,” he wrote via Facebook message Monday night. “And then all at once, like the bulb went out, it was an absolutely magical night. The sun was a black disc, with a golden ring shooting out tentacles longer than the sun was wide … It was the coolest thing I've ever seen, and probably the most spiritual experience I've ever had.”

One of the reasons, he added, was that the experience was one he’d shared cross-regionally, in a way he’d never been able to before, and may not again.

“The two minutes of magic was worth every hour of driving, and the time spent getting to know our neighbors to the south felt just as rewarding, if in a different way,” he said. “Perhaps the otherworldliness of the perfect astronomical alignment helped make fellow Americans seem not so bizarre or far away after all.”