A detail of Maher's piece of "baggage" and accompanying recording. Lucy Gellman Photos.

A child’s blue airplane hangs from the ceiling by a single thread, swaying over a tricycle that is matted with hair and dust. A dresser has come undone, reams of pink tulle spilling out from the top drawer. The bottom drawers wobble like teeth, ready to give way at any moment.

To its left, a thin, blood-splattered sheet covers a body, hardening with the dust that coats the walls, the floor, the ceiling. The body’s shoes—hydrant red, and still dainty as they cup the ball of each foot—remain attached, soles nearly untouched.

These are just a few scenes from UNPACKED: Refugee Baggage, a new installation from artist and architect Mohamad Hafez and writer, speaker and student Ahmed Badr now on view at at Artspace New Haven.

Part sculptural installation, part oral history project, the show runs Sept. 13 through 18 at Artspace's 50 Orange St. gallery space. After it closes, Hafez said he is looking for venues both locally and nationally to host the exhibition.

UNPACKED is funded by the Connecticut Office of the Arts, Wesleyan University’s Center for the Arts, and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. On Sunday, it will end with “Home: Lost & Found,” an evening of music, video and discussion from refugee artists, Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) Director Chris George, and the Hugo Kauder Society at Wesleyan University.

The installation begins with a simple premise: All of us have baggage. But some of us—often the most vulnerable, or the newest to a given country—have more baggage than others, and are not likely to talk about it. Unless there’s a reason to talk.

Over several months, Badr sat down with several of New Haven’s resettled refugees and their families, conducting interviews and recording their stories one by one. As Badr collected those recordings, Hafez brought them to life, nesting a series of intricate, dollhouse-sized models in large suitcases.

Installed, these cavernous pieces of baggage hang open on the gallery's walls, each accompanied by a pair of headphones for the viewer to slip on. Each suitcase and recording reflects a personalized refugee story, criss-crossing the globe from Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran and Syria to Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

That approach is part of Hafez’ larger body of work, which depicts miniature, deeply detailed buildings that have been destroyed in the path of violence. His life as an architect comes into play here: when a wall is ripped away, he knows where long, fang-like reinforcements, demolished plumbing, lighting fixtures and exposed wire will appear. Or, where remaining bits of shrapnel and shell casings will fall.

“I know what happens to buildings when they fall apart,” he said in an interview earlier this year. “When you blow up a building, undoubtedly you expose the rebar and the steel and the concrete slabs … Rubble is a fascinating thing in its own way. And if you see what these bombs do, they expose a lot of foreign objects.”

“I don’t plan any of this,” he added. “My subconscious is telling me: ‘There’s gonna be rebar here. There’s gonna be an electric box here.'”

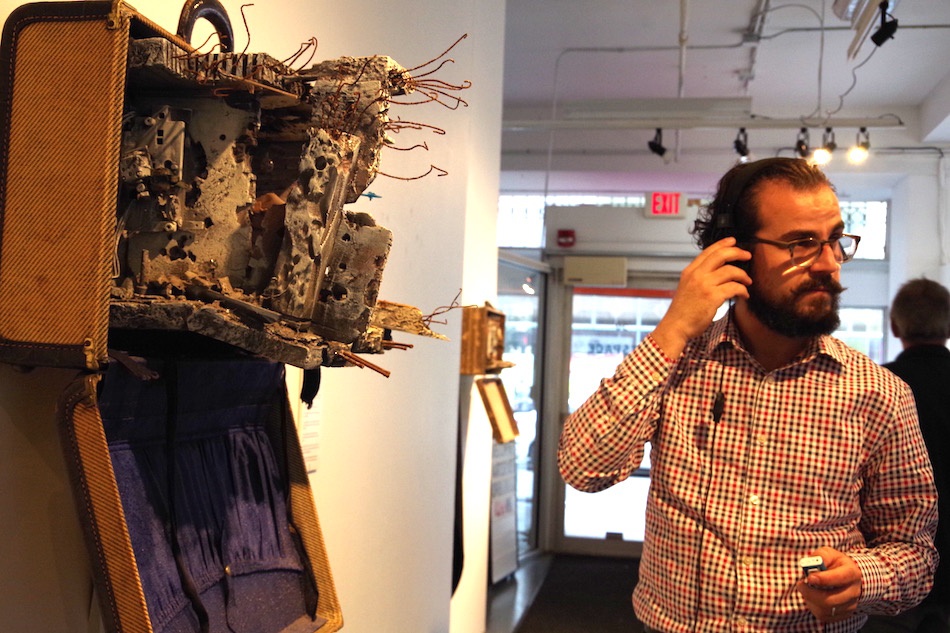

Hafez during the final stages of installation Tuesday evening.

But his connection to the project runs much deeper than that. Born in Syria and raised in Saudi Arabia, Hafez came alone to the United States in the early 2000s to study architecture. When he last returned to Damascus—waiting on a visa in 2011—the city was still standing, its history intact.

But by 2014, that was no longer the case. On Oct. 28 of that year, daily violence compelled Hafez’ brother-in-law and sister to leave their home in Damascus. Together, the two waited until the middle of the night, and boarded a rubber raft with 50 other Syrians to brave the Mediterranean. When they made it across—an outcome of which they had not been certain—they became refugees in Sweden.

An introductory room with video and piles of baggage situate attendees to the exhibition.

Badr too has a personal stake in the project. On July 26, 2006, His childhood home in Baghdad was bombed, tearing the house in half with its sheer force. Just seven at the time, he relocated with his family to Syria, and then to the United States in 2008 when Syria became unsafe.

Since, he has used writing and blogging to demystify the refugee experience for U.S. and global audience. Now a student at Wesleyan University, he has also founded a website where refugees can tell their stories, and listen to others.

UNPACKED takes a deep, affecting dive into those stories. In the first gallery, viewers see not only the shell of a Syrian home—Hafez’ family home—but also Hafez himself, frozen in a photograph as he embraces his mother. She is petite and white-haired, with skin that contains entire histories. She presses her head against his chest, looking to him as he looks back at her. There’s a sense that wherever they are, they are home.

So too with Badr’s family, suspended in time on an opposite wall. As his voice booms from a projection elsewhere in the space, viewers take in details: a charred light fixture and blackened painting on the back wall, the room beside them destroyed completely. A flower pot is somehow unscathed, its pinks still smooth and vibrant as flowers poke through their soil. They are the only thing breathing in the piece.

In each work, Hafez and Badr strike a balance: unending heartbreak, and unexpected, extraordinary triumph. “In Iraq you are allowed to have a gun, but not a camera,” says refugee Maher in one piece, recounting how his work as a young photographer and translator almost got him killed. The scene attached to his recording is not an easy one to stomach: a home sits totally destroyed, with a dead woman’s body still inside and children's playthings scattered, all akimbo from a sudden blast.

But the tale he has told Badr and Hafez, recorded for the exhibition, doesn’t end there. Since coming to the United States, he has used his skills as a photographer and videographer in New Haven, and was recently hired by Google. The house, left behind in Baghdad, is a part of him. But so is this next chapter.

Or Azhaar and Fouad, a couple who fled the Nuba Mountains one at a time for Egypt in the early 2000s, and then came to New Haven as refugees in 2015. As the viewer takes in their “baggage”—a plush, dust-covered high-backed red chair, next to which a black telephone sits untouched— Azhaar speaks in the headphones about her father, so sick he had to stand while praying by the time she left home.

“If he’s here, I would do everything for him,” her voice says. Something catches in her throat. The recording loops back to the beginning.

The stories keep coming. There is Fereshteh, an Afghani-Iranian educator who founded a secret school in Tehran that fell under intense government scrutiny, and ultimately sought refugee status in fear for her life.

Fereshteh's "baggage."

Um Shaham, an Iranian mother of four whose family’s life hung in the balance after an explosive fire in 2003. Amjad, a protester for the Syrian Revolution who watched as the Syrian Secret Police killed friends and neighbors in front of him.

For each of them, a suitcase beckons, challenging viewers to inspect how very far the damage goes. Charred rugs, the edges curled up like toes. A half-standing brick mantlepiece. Flowers dried unexpectedly in a bombing’s wake. Or a rust-flecked Peugeot 504, sign of the Syrian Secret Police.

“Everyone can relate to baggage,” Hafez said Tuesday evening, as he made final tweaks to the installation. “But that doesn’t define us. What defines us—students, photographers, architects—that’s from human to human, honest and unfiltered. This is why we do what we do.”

It’s also not finished. While UNPACKED currently includes 10 families, Hafez said that he and Badr plan to continue working with the city’s refugee population, growing the project organically over the next months and years.

“This is a live project,” he said. “This is a glimpse into the human condition … it’s on us to paint these stories.”

UNPACKED: Refugee Baggage runs Sept. 13-17 at Artspace New Haven. The gallery is open Wednesday and Thursday 12-6 p.m., Friday and Saturday 12-8 p.m. Hafez will be present from 12-5 p.m. on Saturday.