Soto advocates for Yale University to become a sanctuary campus at a protest last year. Paul Bass for the New Haven Independent.

A New Haven “artivist” is responding to Donald Trump’s repeal of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) with a series of figurative drawings — and hoping that they will expand a national dialogue on immigration and xenophobia.

That artist is Juancarlos Soto, a Community Organizer at Planned Parenthood of Southern New England and grassroots organizer in New Haven. Affectionately referred to as the city’s “artivist” by friends and fellow organizers at Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA) and Junta For Progressive Action, Soto has become known for his banners, graphic designs, photographs and illustrations defending immigrant rights.

Now, he has a new subject matter: the 800,000 faces behind DACA, which President Donald Trump moved to end earlier this week. Images that depict recipients’ renewed struggle to remain in the country, and that get across that, in his words, “these are people like your children. They’re young people who are working hard, who are looking for a better life.”

New Haveners at a rally supporting DACA on Tuesday evening. Held at First and Summerfield Methodist Church, it drew hundreds. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Before Tuesday, Soto wasn’t panning on starting a new series. The 32 year old isn’t a DACA recipient; he came to Connecticut from Puerto Rico when he was 15 years old, accompanied by his mother, father, and two brothers. The family settled in the city’s Fair Haven neighborhood just as its demographics were shifting, from predominately Puerto Rican to Mexican and Central American. He said there was “a magic to it, to the sounds and the feeling of that space” — so much so that he still returns each week to buy his groceries, go to restaurants, and get his hair cut.

From that age, Soto relied on his art as the easiest way to communicate. “It was sort of a therapy for me,” he recalled in an interview Wednesday afternoon. “I had left everything behind, and art was something that anchored me.”

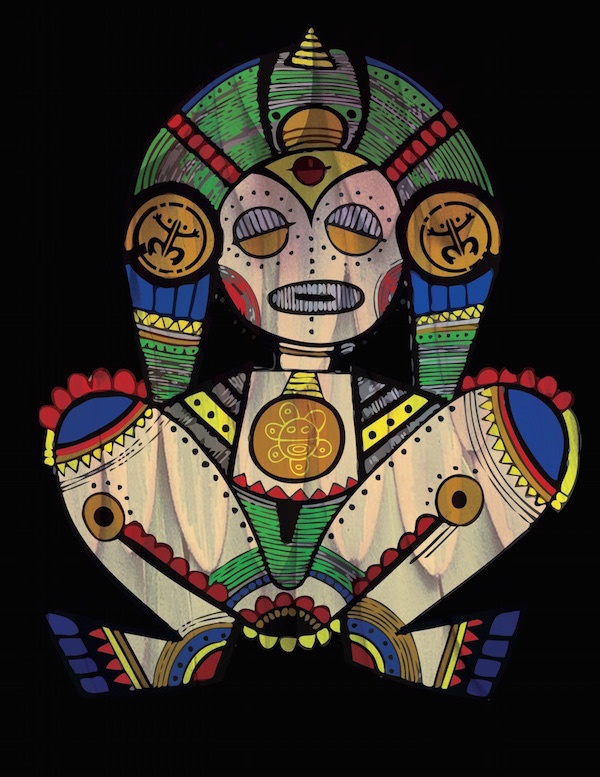

An image from the "Seeds of Resistance" series. Photo courtesy Juancarlos Soto.

As he learned English, he carried a notebook with him at all times, sketching out Spanish words when he couldn’t find their translations. He found himself drawing each day, ultimately attending the nearby Paier College of Art for his undergraduate degree.

As he dove further into the worlds of drawing, painting and photography, he began to use art to “talk about my identity” as a gay Puerto Rican male and committed grassroots organizer.

“It wasn’t until I was in college that I realized I could translate the stories of people in a different way,” he said. “If I can translate that story into a image, I almost feel like it’s a more authentic story. Art tends to transcend borders, language … it speaks like the language of the soul. It gets people to really see what you’re trying to bring up. It goes through your intellectual mind and right into your heart.”

Since, he has bound together his art, activism and advocacy for the community at every opportunity. Last year, he worked with Junta to create and mount Faces of DAPA as the Supreme Court prepared to rule on Deferred Action for Parents of Americans legislation.

In April, he helped design a banner, shirts and signs for a massive May Day march and rally, revamping artist Shepard Fairey’s “Make Art Not War” poster with a flower-crowned Latina. Most recently, he has focused on ancestral Taíno figures, willing them onto the page as a statement on colonialism, displacement and cultural reclamation.

One of Soto's recent Taino figures. Image courtesy Juancarlos Soto.

Which is also how Soto began devising a DACA series on Tuesday, as Trump set into motion its repeal. That morning, he had been drinking coffee at home with his mom when Attorney General Jeff Sessions appeared on the television, declaring DACA’s end as “the compassionate thing to do” for the country.

In that moment, Soto said he knew that he needed to do two things: get on a train to New York City, where a massive protest was planned at Trump Tower, and start working on material that reshaped the conversation.

In a series of digital illustrations, he plans to depict the youth and families behind DACA, drawing a number of the law’s recipients coming out of the shadows, and safely into the light.

He said he can see them already: hardworking kids, some with multiple jobs on top of school, who are using DACA to earn a better—and safer—life for themselves. Who may not have returned to their birthplaces in almost 18 years or more. He said he is hopeful the series will attract viewers from both political camps, who are willing to have a more robust discussion about the repeal once they see the images.

“My goal is to find a way to override the ego in people that tells us that we’re all different, that we’re all separate,” he said. “From a distance we all look different, but when we get really close, we’re all made of the same stuff.”