Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | Artspace | New Haven | New Haven Correctional Center | New Haven Public Schools

In a white-walled room at the New Haven Correctional Center (NHCC), Daniel Watts was preparing a month early for his first City-Wide Open Studios. In one hand, he held a small microphone to his mouth, checking his p’s to make sure that they weren’t popping too hard. Seated inches away, artist Maria Gaspar clutched a recorder.

“Puh, puh, puh,” Watts started. “That sounds good. Oh, that sounds really good.”

Then, after a breath, “I want to talk about liberation. We gon’ talk about liberation, and we gon’ have some fun.”

Watts, 34, hasn’t worked with City-Wide Open Studios (CWOS) before. Born and raised in New Haven, he’d heard rumblings of it, but never investigated further, or considered exhibiting. But he’s a close fit for this year’s festival: A passionate musician and DJ, and lifelong family guy in the community. He’s also an inmate at NHCC, where he landed after violating his probation on a gun charge earlier this year.

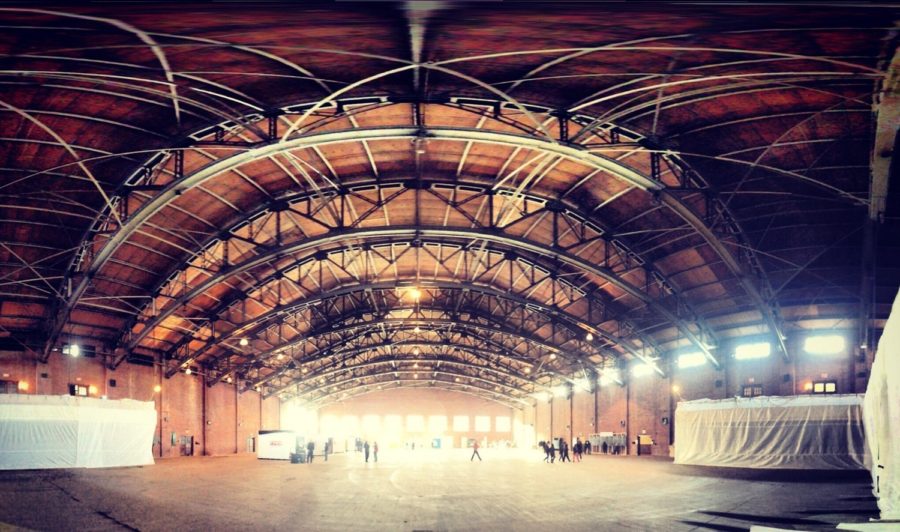

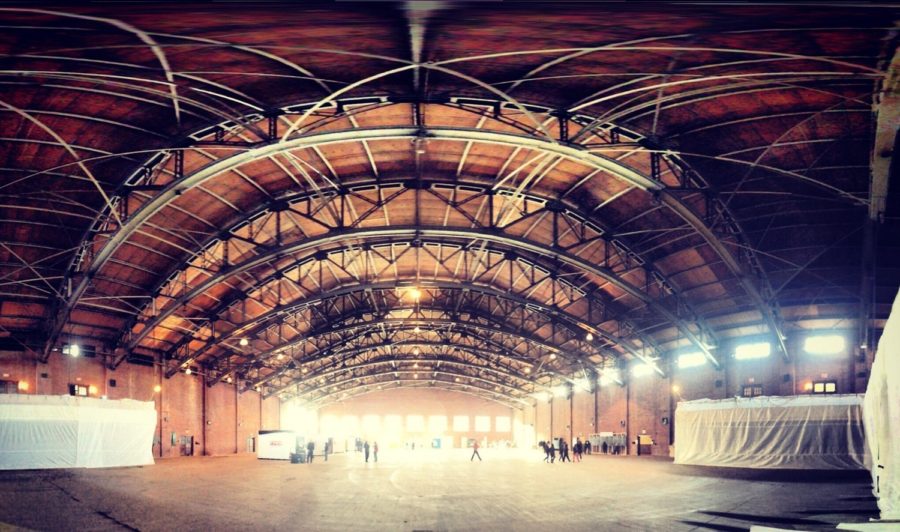

The Armory. Photos were not permitted inside the NHCC. Photo courtesy Artspace.

The Armory. Photos were not permitted inside the NHCC. Photo courtesy Artspace.

With nine other inmates — some of whom will have been released by the time this story runs — Watts is a member of “Sounds of Liberation New Haven,” an audio commission from Artspace and Chicago-based Gaspar.

A mix of prison radio, oral history, and public art installation, the piece will premiere during CWOS’ Armory Weekend, held Oct. 14 and 15 at the city’s Goffe Street Armory.

The project dovetails with this year’s theme of fRact/fiction, based on the “too tidy distinctions we make between ‘reality’ and ‘illusion,’ ‘fact’ and ‘fiction,’ and ‘history’ and myth.” Meant to be played on loop and in multiple locations, it comprises recordings from ten inmates at the NHCC, and from 11 students from James Hillhouse High School, Metropolitan Business Academy, New Haven Academy, Wilbur Cross High School, and the Educational Center for the Arts (ECA).

In late August, Gaspar worked onsite with both groups to solidify her understanding of the area around the Armory, from sprawling De Gale Field to the nearby Saint Martin Townhouses to the NHCC itself. To each group, she posed the same question: What does liberation in New Haven sound like? What does liberation to you sound like? And what do those sounds even mean?

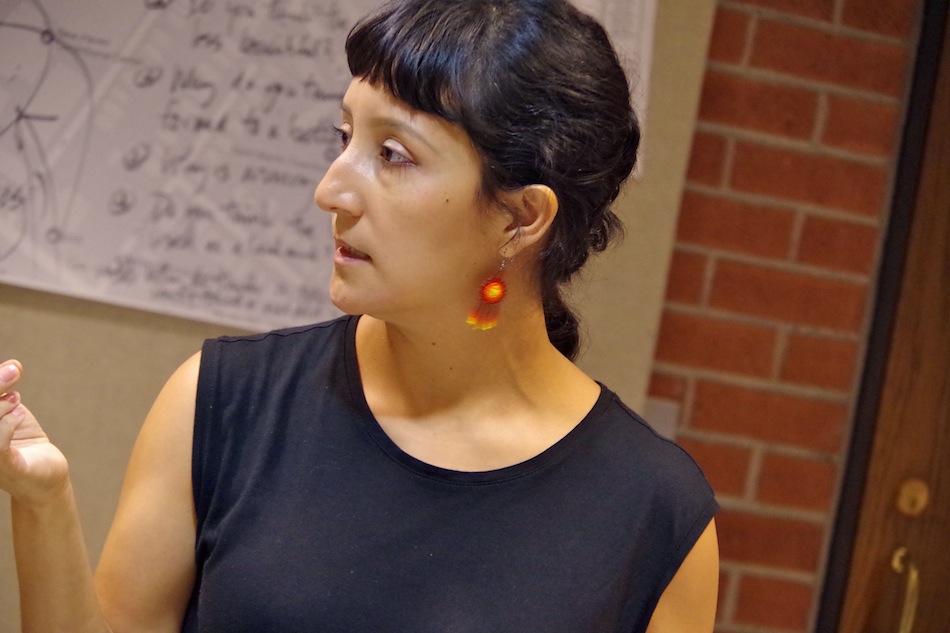

Gaspar outside of the Stetson Library, where she held classes on audio recording in late August. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Gaspar outside of the Stetson Library, where she held classes on audio recording in late August. Lucy Gellman Photos.

For Gaspar, opening those questions up to the community is at the heart of the project. Born and raised in Cook County, Ill., Gaspar said she grew up aware that her neighborhood wasn’t seen as a luxe tourist destination, but as the site of a major prison. Several years ago, she began interviewing inmates at the Cook County Jail, asking them to record their own “sounds of liberation” in song, spoken word, poetry, letters, and rap. After meeting Artspace Director Helen Kauder at an “Arresting Patterns” conference in New Haven in 2015, she signed on to take the project to New Haven.

In the lead-up to Armory Weekend, she has done three site visits to the Elm City, meeting students, residents, inmates and community management team members in the Whalley-Edgewood-Beaver Hills (WEB) neighborhood. She has also been working with the state’s Department of Correction for the better part of two years, to ensure the project’s wellbeing in the NHCC.

“We’ve spent quite a bit of time really thinking through not only the art project, but all of the various elements of making a strong project that is relevant and meaningful to the community that it’ll be taking place in,” she said via phone in August, just before her trip to New Haven.

Unique Jones interviews Catherine Moore, whose senior group is held each week at Bethel AME.

Unique Jones interviews Catherine Moore, whose senior group is held each week at Bethel AME.

“Because it’s gonna be public, because it’s gonna take place during an open studio … it was really key to identify: What are the communities that exist in and around that space? Who is the audience, and maybe even … who do we want the audience to be? Who is missing and who do we want to draw to the conversation?”

It is also an earnest attempt to regain the neighborhood’s trust — and the city’s — after a chain of CWOS missteps last year. In 2016, the organization selected Gordon Skinner’s painting and collage “Cops” as one of its commissioned works, mounting it outside the Goffe Street Armory without consulting any city employees.

In the work, a fat, grinning pig bats its lashes, cocking its bright pink head just slightly to the side. On top of that head sits a blue, black and yellow police hat. Around that head are various collage elements: glossy, disassembled photographs of Marilyn Manson and an unspooled cassette tape, all attached to a milk crate.

Skinner's piece last year. David Sepulveda for the New Haven Independent.

Skinner's piece last year. David Sepulveda for the New Haven Independent.

It didn’t take long for the work to draw attention. After a cop complained about it to Parks, Recreation and Trees Director Rebecca Bombero, the piece came down and was moved back to Artspace’s 50 Orange St. gallery for viewing. From October to December, the organization held a number of public discussions around the decision, drawing hundreds of artists, organizers, and city officials to its downtown offices to discuss what exactly had gone wrong.

The verdict: all parties involved had been reactionary, but Artspace also hadn’t taken the requisite steps to alert the neighborhood, or the New Haven cops that patrol it by foot, bike and car each day. Nor had the organization talked to the NHCC, which the piece faced from Hudson Street.

“We’ve done a lot this year to kind of make the process more community-based,” said Kauder in an August interview, noting that there’s been renewed attention toward diverse neighborhood involvement. “I think we need to be in close communication with the city. The Goffe Street Armory is a city property, and I think Gordon’s project — which certainly responded to current, keenly felt issues — was maybe one of the projects that didn’t go through the same process as some of the other commissioned pieces.”

“I think the city felt a little blindsided by that project,” she added. “This year, all the projects are getting an early screen with the city.”

“I think it’s important to recognize that we’re a partner with the city in the City-Wide Open Studios festival,” added Artspace Curator Sarah Fritchey. “I mean, the city is in the title itself. We really share a set of interests in supporting multiculturalism in New Haven, and giving voice to people that aren’t necessarily celebrated as leaders in their community.”

Voices like those at the NHCC, which primarily houses prisoners awaiting trial and finishing their sentences. (Photos inside the center were not permitted for this article). On a sticky Wednesday in August, Gaspar arrived at the building with a tote on one arm and Trader Joe’s bag filled with recorders and microphones in the other. Four sliding doors and a tote bag deposit later, she entered a small white room, the walls lined with sturdy chairs and old computer monitors. Nine faces (one of the participants was sick for the session) greeted her with wide smiles and widened eyes.

“How’s everybody feeling today?” she asked. It was the final day of the “Sounds of Liberation New Haven” recording.

The room came alive. “Optimistic,” bubbled up from one corner. “Disappointed,” from another. “Anxious.” “Grateful.”

“I’m feeling mixed,” said Joseph Paris. He brought a bound notebook over to Gaspar, opening its black and white cover with a flourish. Inside, careful handwriting filled each page in blue ink, words dancing even in the marginalia. In his three weeks at the center, he had written an entire album on those pages, titling it Render. He wasn’t planning to read it because he wanted to record the whole thing when he gets out, he said.

Others had already made their recordings, and were reflecting on the week they’d had with Gaspar. On one side of the room, Watts was deep in conversation with 27-year-old Omari Jones, recounting an interview that the two had done with each other the day before.

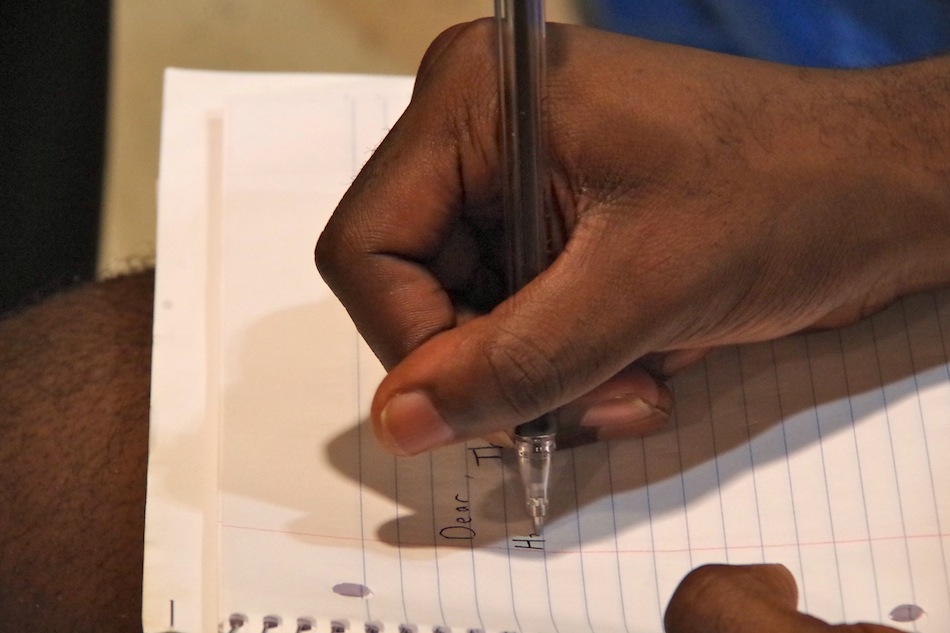

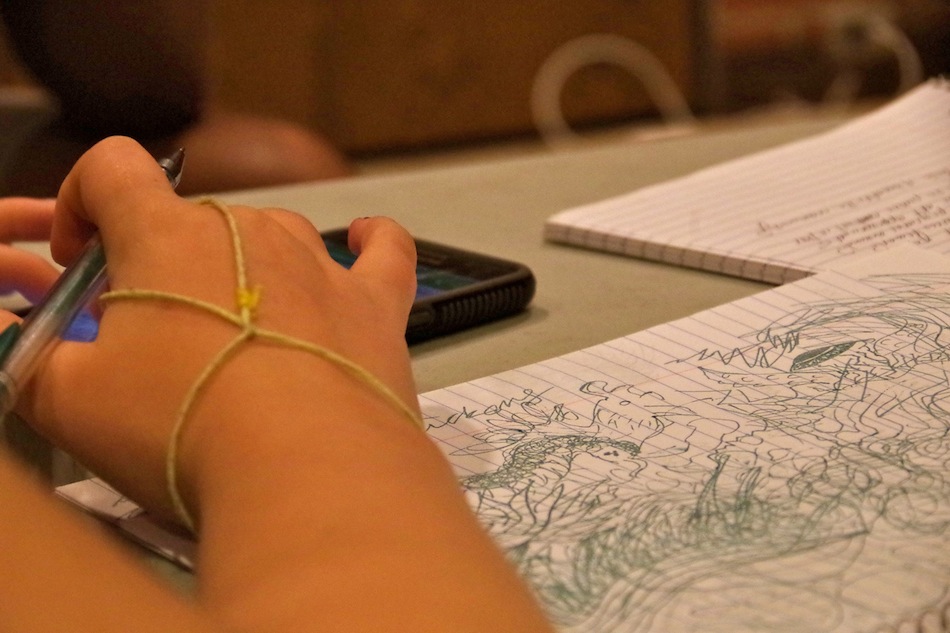

A scene from Gaspar's audio workshop at Stetson Library.

A scene from Gaspar's audio workshop at Stetson Library.

Jones came to the NHCC after violating his probation on a 2014 gun charge. Living at Blake Street and Osborn Avenue, he had purchased a firearm illegally to feel “safer in that neighborhood” a few years ago. He carried it in his backpack. Which did make him feel safer, until he was arrested for it.

“First off, there’s a lot of intelligent and talented people here,” said Jones. “She’s [Gaspar] opened our eyes to that and made us hopeful again. There are things that go on in the hearts and minds of inmates, especially guys — and you see that there are other people in the world that do care.”

“The fact that she would show up, that the news would show up, shows that somebody other than our family cares. I’ve been - I am - grateful,” Watts added. Born in the Quinnipiac Terrace housing projects, Watts said he has lived “just about everywhere in New Haven,” including close to the Armory on Orchard Street.

Of the interview he and Jones had done as their signature “sound” of liberation, he said it had helped him think about how he would address larger audiences about crime, recidivism, and the prison industrial complex.

The two weren’t alone. “It’s pretty amazing to me that nine of us could come together and create these,” said Tobias Wise, a 21 year old who violated his probation on an armed robbery charge and is now serving a five and a half year sentence. He paused for a moment, his eyes saucer-like and soft as he spoke. “I’ve really enjoyed it, I see things different.”

Originally from Fayetteville, Wise moved to New Haven in 2009 to be closer to family. Last year, he was arrested for an armed robbery in the Willow Street area of East Rock, a crime for which he said officials “got the wrong guy.” In recording his own sounds of liberation, he said his thoughts have drifted to his kids: Malchi, who is 5, and Torryn, who is 4 months.

Devon Smith with Alex Jones.

Devon Smith with Alex Jones.

“I shouldn’t be in jail right now,” he said. “I should be with them.”

Earlier that same day, Gaspar’s team of high school students had worked hard to collect narratives from the surrounding neighborhood. After a “Sounds of Liberation” boot camp at Stetson Library, the 11 headed out in the Armory’s general direction, fanning out over Goffe, Hudson, and Orchard Streets and Sherman Avenue. Just outside of Bethel AME Church on Goffe, Hillhouse student Unique Jones approached Catherine Moore, whose senior committee meetings are held at the church.

“Hello,” she said. “I’m a student with Artspace and we’re doing a project about this neighborhood.”

As Moore spoke to Jones about the Armory’s past life, Hillhouse junior Devon Smith trekked across De Gale Field, chasing down Hilhouse teacher Alex Sinclair for an interview about the neighborhood’s young people.

Others in the group chose to write poems, original music compositions, and letters for the project. ECA, Wilbur Cross and Metropolitan Business Academy trio Anton Kot, Jennifer Lopez and Winter von Kohler got into the nitty gritty of writing a song, Leaning over her notebook, Hillhouse sophomore Janyel Campbell reworked a few lines in preparation for a recording session at Baobab Tree Studios the next day.

Learning right from wrong/teaching myself how to be strong/The city that was first here is now long gone.

So how do I stay strong? How do I fight on? How do I push back? How do I live on?

Sounds of Liberation runs Oct. 14-15 at City Wide Open Studios’ Armory Weekend. Artspace is partnering with WNHH Community Radio (103.5 FM New Haven) to play the recordings to a wider audience before and during that weekend.