DeMeo: “It will always be my artistic home, no matter where in Connecticut I live.” Lucy Gellman Photo.

A New Haven artist is circling back to her roots in a place she never expected—amidst white tablecloths, antipasti, and Maryland style crab cakes.

That artist is Kathleen “Cathy” DeMeo, an Old Lyme-based printmaker who works out of Creative Arts Workshop (CAW) on Audubon Street. For years, she said in a recent interview with The Arts Paper, she’s been struggling with the label of “artist.” Now she’s wearing it comfortably—as her first solo show, “Soho to Shore,” runs through Feb. 24 at Christopher Martin’s on Clark Street.

The show comprises two years of work with monotype printing, a painterly process in which an artist applies ink directly to a plate, lines the plate up with paper, and runs both plate and paper through a printing press. Unlike intaglio techniques like etching and engraving or a relief process like woodcut, there’s no carving involved, and an artist can’t make multiple impressions.

Instead, monotype printmakers work with one image at a time, sometimes wiping down and re-inking the plate for a layered design. Monotypes may go through a printing press multiple times, but only ever result in one piece. Occasionally artists reprint the plate, but that is called a "ghost impression" or simply "ghost."

It’s a process that spoke to DeMeo the first time she met it, in a nighttime studio class at CAW two decades ago. Working full-time at the state’s Commission on the Arts (now the Connecticut Office of the Arts) and living in Wallingford, she had enrolled in a multi-week, evening session in paper lithography at CAW. When it ended, she found herself coming back for more.

Under the watchful eye of teacher Maura Galante, DeMeo learned about this thing called “monotype,” where she would have only one impression of her work at the end of the day. It was, she learned, the least printerly of print processes, the weird cousin to painting who sits, decorously, in the corner during dinner parties. For an artist still finding her medium, it stuck immediately.

“I was never interested in making more than one of anything,” she said. “I was a potter for a while, and wheel-throwing didn’t interest me because that was about … getting your eight mugs to look exactly alike. And then I discovered hand building. That’s what I wanted to do—every time I went into the studio, it was something new and different.”

So too was it with monotype: she could spend hours laboring over a single print, setting up the shapes and colors so they layered just-so. From a single class, DeMeo went on to try out different patterns and forms in her work, layering circles, lines and sometimes even collaged paper elements before fiddling with geometric abstraction.

But the artist never expected that those lessons would lead her to exhibit anywhere, much less an East Rock restaurant. The evenings on which she had class were frantic, and left her exhausted: she found herself rushing home from Hartford, throwing something together for dinner, speeding to class for a precious 90 minutes of studio time, and then hurrying back home just in time to collapse in bed.

Then as she retired in 2012, she buckled down on her work, committing to five-hour day classes at CAW with printmaker Barbara Harder. She dove into serialized bodies of work, figuring that “if I’m going to be more serious about my art, people kind of need to recognize me for something.” Artists like Joseph Albers and Piet Mondrian, masters of geometric abstraction, were interesting enough to her, but so were street maps, cityscapes, and a palette that increasingly reflected sea and shore.

“It was freeing,” she said. “Some of them start off very spontaneously—I have no idea in the end what it’s going to look like.”

From there, they evolve—an image of land, sprawling out in dainty squares and rectangles, may come to the page and then get passed through the press. Or sometimes, it’ll be a vivid recollection of her time in the Caribbean last year, with bright blue and green tones settling into a linear pattern that becomes an island settling from a bird’s eye view. She’s experimented with what a friend calls “Pottery Barn tones,” seeing how earthy a brown might be, or what collaged, red strip of paper can most closely approximate brick.

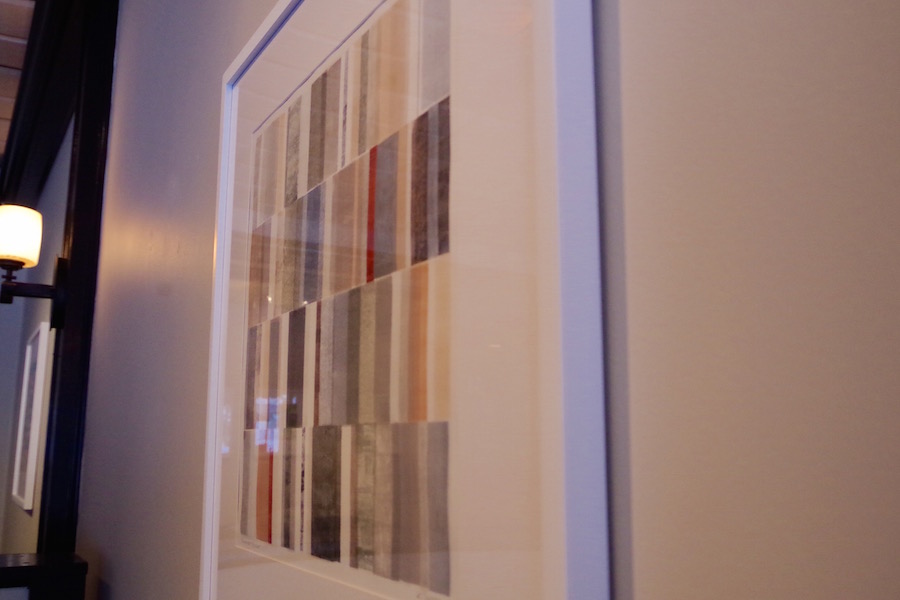

"Tuscan Memory" installed at Christopher Martin's. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Last year, CAW printmaker Liz Pagano reached out to DeMeo about those works. In addition to her artmaking and teaching, Pagano works as a liaison between Christopher Martin’s and New Haven artists, putting rotating exhibitions up where bar and restaurant-goers may least expect them.

The timing was uncanny: Just as Pagano asked DeMeo if she’d consider showing “those rectangle-y things” that she’d been making, DeMeo herself was learning more about the city, lingering after class to get a drink with new friends or see a piece of theater before she headed home. It felt, in every way, like an overdue but unexpected homecoming.

“I’ve always said that Creative Arts Workshop was my artistic home,” DeMeo said. “And I really feel like New Haven, in general, is my artistic home. For me, it’s an arts incubator. It’s one of the greatest concentrations of artists in the state. Yale maybe has something to do with that, but these institutions like Creative Arts [Workshop] and Artspace.”

“It will always be my artistic home, no matter where in Connecticut I live,” she added in a later conversation. “I’m not trying to solve the world’s problems with my art or make a statement. I’m just drawn to color, and I’m trying to create a pleasing composition. It sounds very simplistic. But people react to them, and I’m trying to create a response in the viewer.”

She said that holds true for her now, after a recent move to Old Lyme with her husband. When they arrived there, DeMeo said she found plenty of art—the town was an early cradle for American Impressionism, and it still holds exhibitions, classes and workshops focused on the legacy of that tradition. It just isn’t for her.

Instead, she said she’s come to prefer the uncanny pasta, meat, and beer-scented gallery at the corner of State and Clark Streets, where her work might catch the eye of a diner or outside passer-by. Before the show, she had only eaten at Christopher Martin’s two or three times. As she told friends that her work was going up there, they would stop the conversation to regale her with memories about its place in the community, and their lives. One friend told her he went all the time. Others said that they loved it so much, it had made their list of wedding venues.

“I actually think the show is more accessible than many galleries, particularly smaller ones that rely on volunteer sitters and are only open for limited hours each week,” she said. “I have a deeper appreciation of the restaurant and its place in the community.”

That affection goes both ways, said Christopher Martin’s owner Brian Virtue. As the bar and restaurant enters its 15th year of holding exhibitions, he said it should feel like a homecoming—because the watering hole is meant to feel like a home for creatives as much as chowhounds, sports fans, and runners.

“I think it’s great,” he said. “I can’t count the number of people who have commented on it since it’s been up. It keeps the room fresh … and I also like being part of that local art scene. Maybe we’re not a big art show, but we get to change it up.”