Ashley Sklar | Culture & Community | Downtown | Elizabeth Nearing | Karen DuBois-Walton | Long Wharf Theatre | Outsider | Poetry & Spoken Word | Stacy Spell | Storytelling | Arts & Culture | New Haven | New Haven Free Public Library | Theater

A wide-eyed young woman who watched as the KKK rallied in her town. A hesitant middle schooler undone, then transformed, by space camp. A beekeeper who found that the deepest, most painful stings had nothing to do with insects. All bound by their outsider status, and what sprang unexpectedly from it.

Monday night, those tales and others unraveled at the Ives branch of the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL) as Long Wharf Theatre presented an “Outsiders and Otherness Story Slam.” Held in the library’s basement, the event drew close to 30 people.

The slam is part of Long Wharf’s ongoing community outreach with the NHFPL, which includes a packed lineup of community programs and additional partnership with Sandy Hook Promise for the latest play Office Hour. The show runs now through Feb. 11.

Nearing: Hopefully this is a beginning to a conversation. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Nearing: Hopefully this is a beginning to a conversation. Lucy Gellman Photo.

As news of alleged sexual harassment at Long Wharf spread, staff members present at the slam did not comment on the situation. Long Wharf Board Chair Laura Pappano did release a statement late Monday, concluding that “The only place for drama is on the stage.” (The statement is reproduced in full at the bottom of this article).

But in the library, Long Wharf facilitators focused on silence breakers of another type—community members who were prepared to get up on a stage and tell their stories. Their prickly, slippery, chill-inducing, stomach-churning, still-pulsing stories of being othered. Of being made, in one word, outsiders.

The idea for the slam began months ago, when Long Wharf Theatre Community Engagement Manager Elizabeth Nearing was in the city’s Community Leadership Program (CLP) with NHFPL Community Engagement and Communications Manager Ashley Sklar. The two were doing a group exercise in which a statement would be called out, and those who agreed with the statement would leave their places and walk across the room. Only once did everybody walk across the room on the same statement.

“And that was when the facilitator said ‘I have felt like an outsider’,” Nearing recalled. “It was this really incredible moment to watch everyone move in unison and realize that at the core, this group of like 25 people, that was the thing we most had in common.”

“Those bridges between the stories we tell and the lives we lead—you never know when it’s going to hit something,” she added. “It’s why we do theater … hopefully this is a beginning to a conversation.”

When The Klan Came To Town

DuBois-Walton at a panel discussion last summer, where she discussed fair and affordable housing. On the left is Genevieve Walker. Thomas Breen for the New Haven Independent.

DuBois-Walton at a panel discussion last summer, where she discussed fair and affordable housing. On the left is Genevieve Walker. Thomas Breen for the New Haven Independent.

Before Karen DuBois-Walton had moved to New Haven, before she was executive director of the city’s Housing Authority (also called Elm City Communities), before she led a monthly storytelling night at ConnCAT, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) made an appearance in her town.

She was just a middle schooler then, one of the only Black kids in Gowanda, New York, where her family had relocated when her dad was offered a job as executive director of “a large psychiatric center in Western New York.”

Gowanda was a wake-up call DuBois-Walton never wanted to have. As a young kid, she recalled having a diversity of friends in Albany, New York, where she attended a private school with “a respectable percentage of Black, Latino and Asian students,” a few Jewish students in a majority Christian student body.

Then dubbed “Duby” by her childhood friends, DuBois-Walton grew up with girls of different shapes, sizes and colors, accustomed to “a group of children who came in different packaging—some white, some black, and some light tan like me.”

That changed in Gowanda, which abuts the Cattaraugus Reservation and is home to the Seneca Nation of Native Americans. There, DuBois-Walton’s school was two-thirds white and one-third Native American. That is, until she arrived, and became “literally the only Black person in the building.” Her older sister, then in seventh grade, was in another building on the same campus.

“Very soon, my previously innocent perceptions of myself and others as simply varied expressions of God’s wondrous creations became tainted by racial epithets, stereotypes, and hatred that I hadn’t previously experienced,” she recalled. "My mother—having grown up in the segregated South—found Gowanda only too familiar. But for me it was a newfound and extremely hurtful world.”

It was a world that stalked her down school hallways, into classrooms, and into Sunday school on the weekends. It lurked by her locker and in her literature syllabi. Jumping from fifth to seventh grade, she recalled having to read Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for an English class—and then getting chased through the halls by a student named Lee Halftown, who chanted “Nigger Jim” at her as he ran.

“The experiences made me feel small, ashamed, and embarrassed,” she recalled. “How ironic this torture came from a Native student.”

Those instances taught her firsthand what discrimination looked like, DuBois-Walton said. But they were outmatched just a few years into her time in the town, when the KKK came to protest a hiring decision that her dad had made. DuBois-Walton watched as the group set up shop, burning a cross of lightbulbs and handing out “hateful literature” as a crowd gathered not in opposition, but support. That Halloween, she relived it in horror, as a fellow student arrived at school dressed in full KKK regalia.

No one in her school—“a school full of white teachers and administrators”—said a thing.

“In a town that small, it was easy to assume that those who appeared at the Klan rally in full regalia were likely sitting next to us in our Episcopalian church on Sundays, were shopping in the Super Duper with us for groceries, worked with my father, taught me and my sister in class and hid in plain sight in front of our eyes,” she said.

But she learned a lesson too: Sometimes the best thing to do as outsiders is try to move inside, even if it means moving from one community to another. The year after the rally, her parents “chose never again to be outsiders in that town.” They moved, and didn’t look back.

Spaceship “Outsider”

Larkin: Hell is other 11-year-olds. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Larkin: Hell is other 11-year-olds. Lucy Gellman Photo.

If outsider stories have a launch code, Elizabeth Larkin’s was space camp. When they were 11, they won a summer away at NASA camp in Florida. It was the prize for a model of the Hubble telescope Larkin had crafted for a regional science fair. And it sounded, by their own estimation, like every kid’s definition of cool.

But at camp, Larkin soon discovered that “to paraphrase Sartre, Hell is other 11-year-olds.” Larkin was accustomed to "basic outsider stuff"—hanging around the edges of a situation, instead of being thrust into its cacophonous center. They cried constantly—in a space harness, running through drills and exercises, exploring new science that was supposed to be exciting.

“It was overwhelming to be in the nucleus, instead of in an outer valence,” they recalled. To a smattering of giggles, they added: “That’s a science metaphor.”

Larkin left camp knowing that something had shifted. Slowly, they said, they were realizing that “outsider status could make me look cool—a dangerous loner, like Carmen Sandiego.” They started forging parental signatures, smoking cigarettes, and carrying “mysterious” composition notebooks—the kind with black and white marbling on the cover and a spot for one’s name—to ramp up intrigue.

Suddenly, being an outsider was complicated, because part of it felt good, and part of it felt baffling. In high school, Larkin assembled their first “boy gang,” a group of “three or four blinking boys, who I never kissed,” who became a band of pubescent brothers. They roughhoused. They traded books. Without ever giving Larkin verbal cues, they became a learning ground for being boy-ish, which Larkin realized they were.

“Let me tell you, being sort of trans sucks,” they said. “Nobody takes you seriously. Everyone thinks you want attention. Binding your chest makes you short of breath. You parents friends misgender you at church, making everyone want to die … You want to live on this slick knife edge of androgyny forever, how are you going to give that to yourself?”

The key, they realized, was in embracing outsider status as observer status. They studied their boy gang, a scientist taking fastidious notes as members walked, talked, dressed, talked to their girlfriends.

“It’s how I figured out how to do me,” they said. “With distance, patterns grow clear. From space, you can see everything.”

A Stinging Loneliness

“I’m going to let my charm, I’m going to let who I am, go before me. I’m going to let the love in me and the peace in me show through.” Lucy Gellman Photo.

“I’m going to let my charm, I’m going to let who I am, go before me. I’m going to let the love in me and the peace in me show through.” Lucy Gellman Photo.

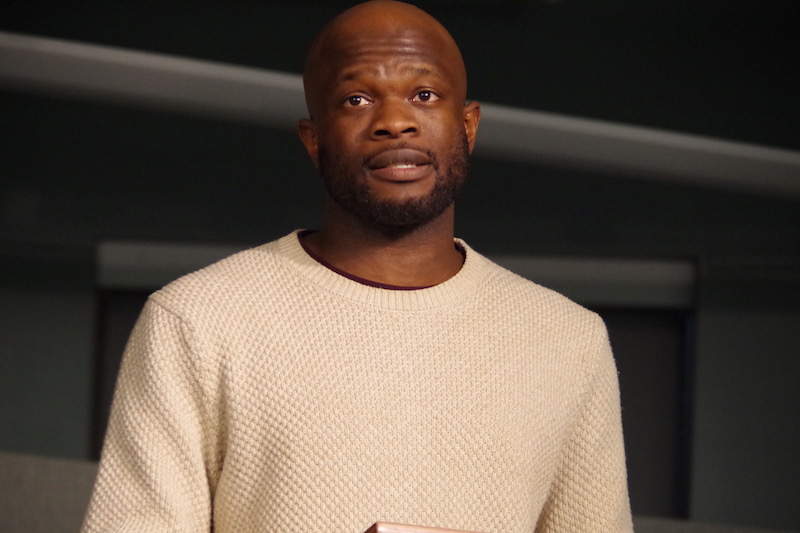

Stacy Spell thought he had a handle on navigating outsider status. A longtime leader with the New Haven Police Department, Project Longevity, and the West River Development Corporation, Spell told Monday’s audience that he’s gotten to know New Haven—its nooks and crannies, its idiosyncrasies, and its microaggressions.

He’s been battling them with stereotype-busting, community-building pastimes for years. Mushroom hunter. Urban farmer. Food justice advocate. Community green thumb. Avid and sharp-eyed birdwatcher, with a specialty in birds of prey. Each comes with its own set of doubters, he said—like fellow, more amateur birdwatchers who listen to him identify Red-Tailed Hawks, and insist that they must be Bald Eagles.

But he wasn’t expecting to find his greatest challenge at a beekeeping workshop. Not after years on the police force, walking around on sites his colleagues wouldn’t go on foot. Not after working with youth to change patterns of violence in the city. And not after forming The Little Red Hen, a community garden on Mead Street in the city’s West River neighborhood, where Spell has lived and worked as an activist for three decades. Most recently, he’s brought chickens in to the garden, adding egg incubator to his list of titles.

Beekeeping, Spell said, seemed like the next logical area of interest. For years, he has been taking online beekeeping courses. Last year, “I finally got up the nerve to join the Connecticut Beekeeping Association.” A friend from the state’s Agricultural Experiment Station encouraged him to attend a workshop in a nearby town. It was out on a farm, with rolling fields, scheduled for a bright fall Saturday. But she also cautioned him that he might be the only person of color there.

Spell shrugged it off. He had been looking for a mentor, and this seemed like the right place to find one. Besides, he said, “there’s not much I fear in this life. I fear God, and that’s it.”

“Anything else, I’m going to let my charm, I’m going to let who I am, go before me,” Spell continued. “And I’m going to let the love in me and the peace in me show through.”

On a calm Saturday morning, he rolled up to the farm in his SUV, wearing a flannel top that made him “look like the rugged outdoorsmen.” He checked in at the farmhouse, scoped out seating. Spell said he could feel that something wasn’t quite right, but tried to shake it off.

“I should have known something was up, because if you had heard a record playing, the record would have stopped and some Rrrrrrrrrr!” he recalled.

"But I proceeded," Spell said. He found a spot up front, where he’d be able to see the talk. On either side of him were two empty chairs. As the room filled up, then reached seated capacity, then became standing room only, no one sat next to him. For a two-hour presentation, he watched beekeepers prance from side to side as they stood, rather than sitting beside the only person of color in the room.

“I can’t make someone sit next to me,” he said, his voice catching just so. “So for two hours, I sat with two empty seats on the right of me, and two empty seats on the left of me.”

The presentation gave Spell a lot of new information to work with. At the end, he skipped the non-question question askers, who made statements about their hives instead of asking how to improve them. Then he approached the presenter and introduced himself.

“I’m new to beekeeping, and I’m looking for a mentor,” he said.

The presenter gave him a name: a scientist and beekeeper at the Agricultural Station who had a grant to teach beekeeping to inner-city youth. Spell took his information, and called the scientist as soon as he returned home. They spoke again, and one more time. Then he never heard from the scientist again.

“This compounded the feeling I felt at this farm,” he said. “That I’m here to learn knowledge … not here to ask for anything except to learn about beekeeping. When you’ve lived this long and got some wisdom, you realize it wasn’t about how you smell, or how you growled, or how meed you could make yourself be.”

He took a step back in time, to the first time he could remember running into the kitchen with his sister, and announcing that “there’s someone colored on television!” to his mom. Then his face grew tight, and he looked up at the audience with wide, soft eyes.

“From 1960 to 2017, not much has changed,” he said. “I am a person who controls my own destiny … who believes in writing my own narrative. I’m a person who is a radical. Who believes in social change. But the irony was that in my maturity, in my wisdom, I still found that I’m an outsider.”

If You Give Them Hope

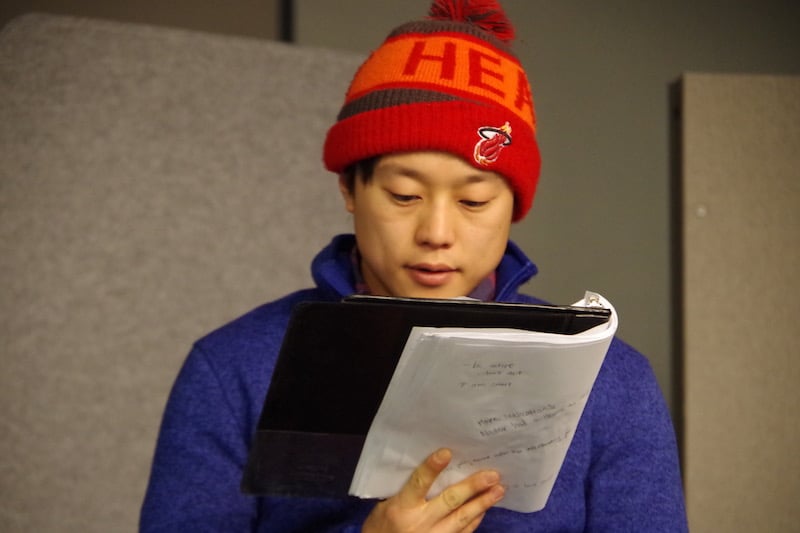

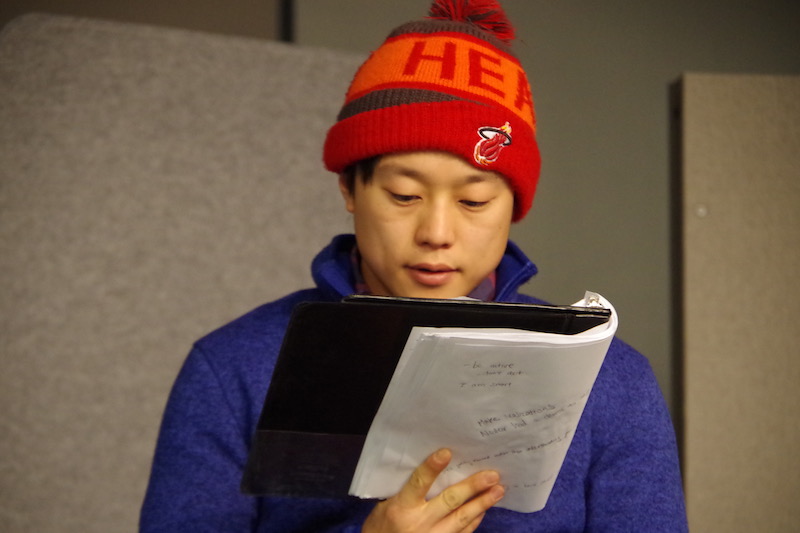

Before the evening was over, Office Hour cast member Daniel Chung also took the stage, to read through a few of his parts—and leave what he’s learned about playing an outsider with the audience.

Chung plays troubled-kid-turned-school-shooter Dennis in Office Hour, a sort of groundhog day string of scenarios that sets and resets several times before the show is over. Diving into a monologue, Chung said he wanted to the audience a glimpse inside the character, that they might relate or know someone in a similar headspace.

“All my life, the only thing anyone’s ever told me is I’m the problem,” he read from the script. “From day one. I am not strong and I believed them. I was just a kid so of course I believed them. I was even received, thank God, someone was going to fix me.”

“What I have, this feeling I carry, I don’t have to keep carrying it. So years of art therapy and speech therapy and therapy therapy, nothing took the feeling away. Nothing made life less painful. And then you know what? I finally figured it out. Figured out what was really going on. What must be going on. I’m not the problem. I’m not the problem and I never was. They were the problem.”

Then he stepped back out of character. Speaking directly to the audience, Chung noted that he’s felt like an outsider before too, and leans heavily on a support network of friends and family when he feels that way even now. He said he lets them remind him “that there are people who care about me, that there are people who support me.”

“There’s people out there who don’t have that privilege,” he said. “They find themselves in situations where they have no hope, where they feel that their purpose in life is to be hated by others, and there’s no one around to remind them that that’s not true. But that shouldn’t be the case.”

“Every night, when I say these lines, it just reminds me that if you show love to a person, if you give them hope, that can do so much,” he said. “That can break them out of this hell of thinking that they’re forever stuck in darkness.”

Office Hour runs Jan. 17 through Feb. 11 at Long Wharf Theatre. For show times and ticket information, check out Long Wharf’s website. To find out more about outreach and Long Wharf’s slate of literary programs, click here. The theater's full statement on ongoing allegations is below.

Statement from Long Wharf Theatre Board Chair Laura Pappano

"Laura Pappano, chair of the Board of Trustees, Monday morning placed Artistic Director Gordon Edelstein on administrative leave, effective immediately pending further action by the full board.

Managing Director Joshua Borenstein will lead the theatre.

Several allegations of sexual misbehavior by Edelstein was reported in the New York Times.

These allegations are unsettling. Long Wharf Theatre embraces equity, fairness and integrity. The theatre is committed to creating a workplace environment where everyone is respected, valued and feels safe. We have policies in place to support that charge.

The institution takes seriously all complaints of behavioral misconduct. Some of these reports are surprising and upsetting. We know of no instance in which a complaint was filed and not acted upon. Many accusations detailed in the New York Times were not previously reported.

That said, we have the highest expectations for ourselves. This theatre values openness, trust, and respect among peers. When those values are compromised, it demands self-reflection. The theatre takes this new information seriously and will use it to move forward.

We simply cannot and will not tolerate behavioral misconduct in the theatre workplace. It takes a tremendous amount of creativity, hard work and talent to make world class theatre.

The only place for drama is on the stage."