Arts & Culture | The Paston Treasure | Visual Arts | Yale Cen

Maybe it’s the hulking, rose-gray lobster, its pincers turned an ashy pink, that yanks you by the bellybutton into the painting. Or the gilded Nautilus cups, fantastical, burly figures etched onto their pearly faces. Or the girl, painted in flat, who doesn’t quite go with anything around her. She opens her mouth, but no noise seems to come out.

So begins The Paston Treasure: Microcosm of the Known World, open now through May 27 at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA). Born out of an obsession with a single, unattributed painting of the same name, the exhibition takes a deep dive into a family’s history, legacy and financial downfall, yoking art with material culture, science, trade and alchemy as it does.

The exhibition is a collaboration with the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, where it will travel after New Haven and where the painting lives permanently. This is the first time it is being shown in the United States, with nearly 140 objects that seek to rebuild its history.

Co-curator Edward Town, with Senior Conservator of Paintings Jessica David in the background, at a press preview earlier this week (full curatorial credits are at the bottom of this article, with information on visiting the YCBA). Town spoke on the importance of the Paston letters, some of which are on the exhibition. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Co-curator Edward Town, with Senior Conservator of Paintings Jessica David in the background, at a press preview earlier this week (full curatorial credits are at the bottom of this article, with information on visiting the YCBA). Town spoke on the importance of the Paston letters, some of which are on the exhibition. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The Paston Treasure centers around its title work: a seventeenth-century painting in the vanitas or still-life tradition, where the decay of objects symbolizes the passage of time. There are peaches turned green, festering like wounds, grapes with ladybugs crawling on their shriveled skins, flowers browning as they wilt together. Just in case the viewer hasn’t gotten the memo—momento mori, so hop to it—timepieces appear on the wall and table, one just inches away from a melted wax candle.

But something is different about The Paston Treasure. Where most vanitas paintings center on organic matter and are not quick to feature people, this is packed to the edges with material goods from France, Italy, England, the West Indies and Southeast Asia. As the eye travels—from the center out, or left to right, or foreground to background—objects seem to multiply. All of them are touched with some degree of luxury: gold filigree, delicate enameled faces, ornate woodwork.

A detail of the work, as a bug braves old flower petails.

A detail of the work, as a bug braves old flower petails.

Two figures are also squeezed in: a Black youth at the left, whose muscles undulate beneath his garments as a monkey poses on his shoulder, and a young girl in the foreground, holding a songbook in one hand and clump of whitening, withering roses in the other. She looks as though she’s been parachuted in à la Flat Stanley, out of proportion with everything around her.

If there are questions the painting raises—why is the canvas so packed? And why is it fading?—that’s the exhibition’s jumping off point. Across eight galleries on the center’s third floor, a team of scholars, conservators, and curators has sought to reconstruct the family’s history of collecting, and in so doing tell the whole story behind the piece.

It is, perhaps, not an exhibition designed with the general public in mind. At a press preview earlier this week, outgoing YCBA Director Amy Meyers described it as “the paradigm of generosity for scholars … what could be better at Yale?”

Whole sections of the exhibition, like a wall of family portraits dating to around the painting and in a dark, Dutch style, seem purely archival, there for purposes of being catalogued and discussed in symposia. The painting itself is a sort of catalogue, freezing in history all that the family has amassed before it disappears.

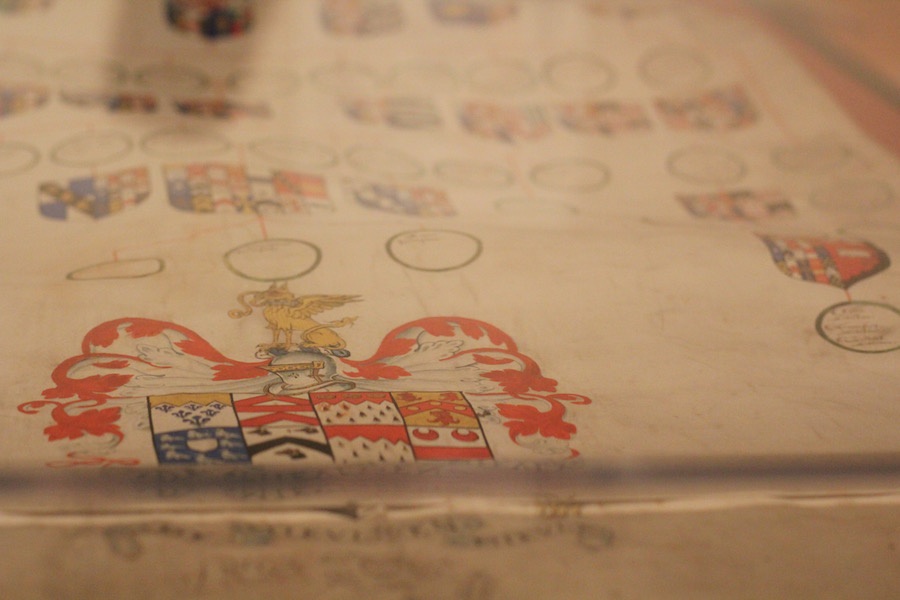

A coat of arms from the Paston family timeline.

A coat of arms from the Paston family timeline.

And yet in their dogged pursuit of answers, curators have cracked a nut that is so essentially human one cannot help but take a closer look. And then another, and then another. From an introductory film walking viewers through technical explorations of the painting, this is the show that breathes new life into an old tradition—not because we are anything like this family, but because it is so much fun to see the lives they lived.

If it were a reality show, it’d be Meet The Pastons, about a wealthy landowning family with bad politics, a buying problem and near-aggressive approach to upward mobility. In front of the painting itself are a series of individual treasures that appear in it: a pair of silver and gilt flagons, cup with a strombus shell, two Nautilus cups, and a mother-of-pearl perfume flask, assembled in India.

From there, unique, quirky and deeply personal objects reveal themselves, leaving a trail of art historical breadcrumbs in their wake. In the second gallery, a number of smaller vanitas paintings give a sense of who the artist was, comprising the same forms and habits that dot the painting. In one, a parrot strikes a pose not unlike that in the painting, where it perches on a book of music with its claws.

A pair of silver and gilt flagons, cup with a strombus shell, two Nautilus cups, and a mother-of-pearl perfume flask, assembled in India all join the painting in the first part of the exhibition.

A pair of silver and gilt flagons, cup with a strombus shell, two Nautilus cups, and a mother-of-pearl perfume flask, assembled in India all join the painting in the first part of the exhibition.

It’s a look, intimate and historic, into family affairs that continues in objects like the Paston family letters, an archive that Co-organizer Edward Town called “a tranche of Medieval history.” Placed throughout the exhibition, they give insight into the family’s collecting practices, but also their history and language. They are a window into collective Paston memory, a brain space punctuated with phrases like "My deare hart," a greeting from Robert Paston to Rebecca. In the first gallery where they are featured, they create a sort of sight line into the next room, where a large vitrine houses a long family timeline, with squiggly lines that leave the viewer wanting to learn more.

Where’s there’s style, there’s also whimsy. Near the exhibition’s halfway point, a gallery titled “Sir William Paston’s World” offers a glimpse into Paston’s animated youth, reassembling some of the treasures he picked up on his travels of the globe as a twentysomething. It’s his rowdy, all-expenses-paid Grand Tour slightly before the Grand Tour was a thing—a good old early modern boys’ trip.

Among the treasures he brought back, a Pietre dure tabletop takes center stage, bright and striking as its colors wink in and out below the gallery’s lights. From coats of arms at its sides, sprawling vines, flowers and ferns wind around the sides, sensuous as they lead the eye to bright birds, and a cluster of gem-like fruit inlaid at the black marble center. Behind the tabletop is a rendering of perhaps William’s greatest catch: a huge, glistening crocodile (this one is on loan from the Peabody).

But there is also a wonderful sense of knowing William Paston, before he is an older Sir William Paston, and while he is still young and curious and uninhibited. In a case on the gallery’s right are sketchbooks on loan from Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, pen still inky in the hands of Patron’s travel companions Henry and Nicolas Stone. There is a momentary reminder—all that you need, really—that Paston and his friends spent time doodling inconsequential things—figure studies and people on the street and costumes of the period.

So too in the next gallery, where a cluster of family portraits take a backseat to a child’s cloth in red silk, velvet and gold lace. As the gallery brings viewers through history—the Pastons were able to solidify their status when William married Charles II’s legitimate daughter, whose horse-faced likeness is on the wall—the material object comes alive, the softness of the silk and luxe lace almost palpable through the case where it is housed.

It’s a piece of Paston history that leads right into the climax of the exhibition, a reconstruction of the family’s “Best Closett” at Oxnead Hall, installed under the watchful eye of King Charles II of England. From every angle, shiny and beautiful things beckon: heavy, glinting jewelry, rare string instruments like the ones propped up on the canvas, shell cups showing off their pearlescent, gleaming surfaces.

There are cases filled with treasures everywhere you look, like an almost-translucent carnelian cup, barely thicker than a fingernail, in which you can spot a reflection of its gold base. Or a dainty cameo, oil on lapis lazuli, of Perseus Rescuing Andromeda. On a wall closer to the end of the gallery, scholars have recreated a recording close to what the girl in the painting would have been singing, filling the room with friendly ghosts.

It’s here, delighting in these treasures, that you learn it won’t end well for the family: they were losing their wealth, a casualty of the times. The following gallery, and last in the exhibition, is dedicated to Robert Paston’s quacky and unsuccessful attempt to earn it back through alchemy—in this case, turning metals into gold—where the best of science is able to imitate nature itself. On a table in the center of the room, Senior Paintings Conservator Jessica David has set up a display of handmade dyes, Paston's pastimes spring to life with ground Paston blue, and crushed bug shells for cochineal red. A diamond-shaped clock from the period winks out on a wall close-by, a reminder that time is finally up.

It’s a sad story until it’s not. The objects are umbilical cords to history: They anchor us to people with whom we have little in common, and yet we learn to love. They are people who live, and people who die, and people who are scared they won’t be remembered after they go. People who owed things and lost them. People who experimented, because they thought they could get it all back. If you think you haven’t been there too, you’re kidding yourself.

The Paston Treasure: Microcosm of the Known World is on view at the Yale Center for British Art through May 27, where it is free and open to the public. The exhibition is curated by Andrew Moore, former Keeper of Art, and Senior Curator, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery and Organizing Curator Nathan Flis, Head of Exhibitions and Publications, and Assistant Curator of Seventeenth-Century Paintings at the YCBA. Collaborators on the exhibition include Co-organizer Edward Town, YCBA Head of Collections Information and Access, and Assistant Curator of Early Modern Art; Francesca Vanke, Keeper of Art and Curator of Decorative Art at the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery; Jessica David, Senior Conservator of Paintings at the Center, and Elisabeth Fairman and Sarah Welcome, Chief Curator and Assistant Curator of Rare Books at the YCBA.