Maafa: Ghosts of the Atlantic II , 48 x 36 in. Acrylic/mixed media on canvas. Photo courtesy WCGMF.

The bodies jump out first. Thick black paint from which torsos emerge, then arms and legs.

They tumble through space and multiply the longer you look: first it’s 10, then 15, then 25. They are the gateway to everything: deep blue and green paint, smudges of purply red, globs of gold that break through from the top left. Orange and green sea-grasses sway at the bottom. Then the realization hits you in a wave: These are bodies that have been thrown overboard, falling not through sky but ocean to their graves.

Detail from Maafa: Ghosts of the Atlantic II. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Maafa Ghosts of the Atlantic II is just one of 35 works in Rhinold Ponder's The Rise And Fail of the N-Word, a new exhibition at Kehler Liddell Gallery through March 18.

A mix of acrylic painting, multimedia collage, and original poetry, the show is funded by the William Caspar Graustein Memorial Fund (WCGMF).

The exhibition’s public programs, also supported by the fund, begin this Wednesday with an opening reception and Q&A between the artist and Ifa priest, clinical social worker, and community organizer Enroue Halfkenny.

The exhibition, which opened last year in New Jersey, is one of the first times in four decades that Ponder’s art is taking center stage. Born and raised in the 1960s on the south side of Chicago, the artist first developed a love for acrylics in high school, where he forged an academic path as the oldest of eight kids.

But it took a backseat in 1977, when he pursued an undergraduate degree at Princeton University, and then master’s degrees in journalism and African-American Studies at Boston University, and then a law degree at New York University. Art always pulled at him, but so did a growing law practice in New Jersey, where he saw clients for 30 years.

"How do I make the ugly beautiful, and how do I make the beautiful ugly?" Lucy Gellman Photo.

When he closed his law offices last year ("It was wonderful!" he recalled), Ponder knew that he wanted to go back to writing and visual art full-time. And he wanted to make it about something that wouldn’t leave him alone— in his practice, in his daily interactions, and at home, he had realized that “across our experiences, we have a very difficult time talking about race.”

People he talked to were increasingly siloed, and yet also increasingly interested in talking about race, racism, and racial disparities in American society. Particularly white people, for perhaps the first time in his life. But they didn’t always have the tools to do it.

“I find that the discussions become difficult because we don’t have a common understanding of language,” he said. “And at the core of that is the word nigger. It’s there at the very core.”

“One of the questions became: How do I make the ugly beautiful, and how do I make the beautiful ugly?” he added. “Which forces you to rethink what you think you know.”

Of the artists Ponder commissioned via Fivver, the Americans returned black and white ad designs on the first draft. Lucy Gellman Photo.

It was around that question that the works began, first with constellations of ’N’ Word advertisements, and then with acrylic and multimedia works and poetry. Posting on the marketplace website Fiverr, Ponder asked 20 artists from around the globe to create an ad-like label with the word “nigger” at its center, the only text that appeared in the image. 10 of the artists were American; 10 were from other countries. Only one, who he found through an outside ad agency, was Black.

“I gave them one instruction—no black and white,” he recalled.

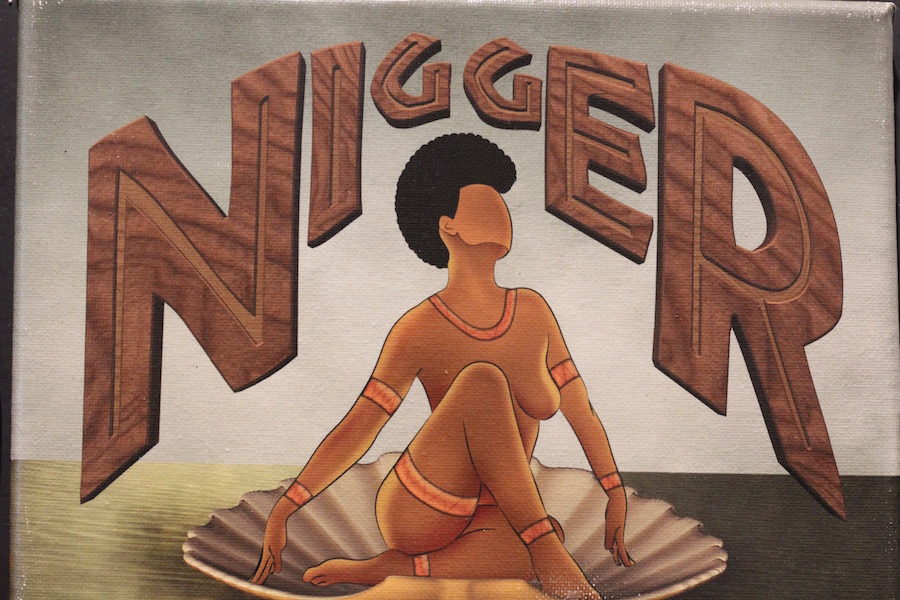

The design Ponder received back from an artist in the Dominican Republic. While he said he was first hesitant in the depiction of a Black woman, he ultimately saw it as in line with the show's juxtapositions and ironies. Lucy Gellman Photo.

But the majority of American artists returned with black and white designs. The international artists stayed within the rules: they returned with colorful, commercial logos with whimsical lettering, bright designs and blocky fonts.

One of them, from the Dominican Republic, featured a slim Black woman, afro out, cross-legged atop a shell like Venus de Milo. The Americans had returned static, grayscale logos. It was proof positive, said Ponder, of “how racism destroys our thinking and our productivity, and destroys our ability to think.”

While he sent them back to the drawing board, he dove into his own work for the exhibition, ultimately drawing on 35 works comprising seven different series.

White, washed out canvases with the titular ’N’ word became reflections on Ralph Ellison, whose Invisible Man remains one of the most formative works on Ponder’s career.

In one, titled Cracked True White Painting with Blemishes II (for Ralph Ellison), book clippings are collaged onto the canvas, words barely visible from a foot away, and no more than an orange-brown blur from across the room. The word, painted like a ghost onto the canvas, is almost invisible to the human eye.

So too with all-black paintings (“What is white in this country except the opposite of black?” he asked aloud as he installed the show), with the ’N’ Word painted on in a slick, velvety shade of black. In the exhibition, he’s placed those front and center: A black canvas in a black frame hangs alone on a freestanding wall, at the end of a straight line from the gallery’s front door to its back room.

Nigger Rich I sits at the center of the gallery, on a freestanding wall. Lucy Gellman Photo.

It is a nod to artists who came before—Ad Reinhardt, Josef Albers—that is willing to talk about race. At its center, the word NIGGER stands out from the canvas in gray, so ashen it looks more like graphite than acrylic paint. It’s obscured by another word, RICH, with a cent sign striking through opposite edges of the C. Other large-scale paintings whisper at it from the surrounding walls.

Close-by works take a whimsical approach—or so it seems—revealing their gravitas only as you approach. In acrylic and mixed media, four grids of bright Keith Haring-like figures, caught mid-movement, raise their black arms to the viewer. Their bodies are marked as targets, caught in the crosshairs of a gun we can't see. Hands Up, Don't Shoot, Shot Damn I-IV reads a set of labels. The works strech out, an unending cycle of bodies that repeat without ever being asked.

A detail of Hands Up: Don't Shoot II. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Throughout, the paintings have a sharp and unflinching eye towards history: Ponder’s reminder that the past informs the present, as the present will the future. By the center of the exhibition, a woman’s body sinks in thick, marbled blue-green water, her torso heavy as one leg flies upward, and her arm pulls her down.

Inside her belly, a baby floats in its own sea of fluid. We are privy to it all: the watery grave where she will rest, the body that is supposed to be life-giving that is dying before our eyes, the hundreds of thousands of flames that were snuffed out like this.

I am your vessel — I cannot breath, begins a poem beside her.

“You know you are done with a work when you cry,” said Ponder, tracing her frame with his eyes.

It is an exquisite, grotesque, moving case for reparations. To the right of the gallery’s front door, Ponder has installed three pieces tracing white terrorism from an abstract landscape to Birmingham, Birmingham to Charleston, Charleston to Tulsa.

Abstract Nigger I, 30 x 40 in. Acrylic on canvas. WCGMF Photo.

In the first, lines spool outwards from an origin point we cannot see, somewhere just off the canvas. They are the purple of fresh bruises, criss-crossing a field of light and dark blue, smudges of of green, hints of red and yellow.

Inside and on top of them ride phrases: Nigger Please. Nigger For Life. My Nigger. Ten Little Niggers. A few phrases hover above, unmoored, as though they may fly off the canvas and burrow into another.

This is the gem-colored landscape that Abstract Nigger II: From Birmingham To Charleston II and Abstract Nigger III: Tulsa Oklahoma are built on: too aesthetically pretty not to come closer, then to solemn, too torturous, to tear your eyes away.

Ponder weaves a web between events: the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963 and Charleston AME Church shooting in 2015. The 1921 riots in Tulsa’s Black Wall Street neighborhood, which left 300 dead and 35 blocks burned to the ground. On an opposite wall, red and blue silk screens of Trayvon Martin look out at the viewer. His eyes, tired and kind, are questioning pinpricks.

“A lot of what I’m trying to do is to help people draw connections,” he said. “Because—particularly for those who are not of color—some people want to know ‘Well, why don’t just let it go? Why are you still concerned about racism? It’s all changed.’”

“Well, no,” he said. “It is continual. It is an inheritance that keeps on giving. How do you get people to grapple with the contradictions, the ironies, and the juxtapositions? What we do instead is we create fictions that make it easier for us, but block out lots of truths.”

As he painted feverishly, Ponder said that his work confirmed his belief that “we give the word so much more power than it probably deserves.” He has shown it, ultimately, in plain color, in bolded design, in advertising lingo, in collages where it is overpowered by Ellison’s words or magazine clippings or thick paint, so heavy it might drip over the edges of the piece.

Detail of Keloids and Scars II, acrylic and mixed media. Lucy Gellman Photo.

“‘Nigger’ is nothing but an invention,” said Ponder. “An invention to maintain a certain economic system which then had traditions and cultures around it … But it’s a fiction. It’s still a fiction.”

“In order to do this particular project, and in order to view it, you’ve got to deal with yourself,” he added. “Who you are, how you understand your place in society, what you think your purpose is—all of that.”

The Rise And Fail of the N-Word is on view at Kehler Liddell Gallery from now through March 18. Find out more about events by visiting Kehler Liddell or the William Caspar Graustein Memorial Fund online. Check out Rhinold Ponder's work here, or at the Facebook group “Beyond Black and White."