Fatima Rojas' portrait of her daughter on a family hike. "It represents the life, the struggle, the maternity of some of us," she said of the exhibition. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The girl is young, hands clasped, hair falling past her shoulders. Bright green jacket, zipped to the neck. The woods unfold behind her: A carpet of red and brown already on the ground, some trees still holding into their green foliage.

You can’t see her face. A thickly veined leaf, red with New Haven fall, is almost as big as her head, and hovers before it. There’s a rare glimpse of her eyes, deep brown and trusting. As if to say, I know this photographer; she is part of me and I of her. As if to say, in another life, this camera may have passed me by.

Graduate student Megan Fountain, a longtime activist with and member of ULA, takes in the exhibition.

So unfolds La fotografía de MULA, an exhibition of seven Latina photographers tucked away behind an insurance company on Grand Avenue. Organized by Yale Student Julia Char Gilbert with Unidad Latina en Acción (ULA) and The Schell Center for International Human Rights at the Yale Law School, the exhibition opened last weekend and is on view by appointment.

The exhibition centers around its acronym: Mujeres Unidas Laborando por el Arte, the shorthand for which translates to “mule” in Spanish. It’s a tongue-in-cheek reference from the photographers—they are citizen photojournalist but also “mules” in their community, shouldering the heavy burden of child rearing, marriage, activism, and their own immigrant narratives with certain, steady footing. They are tired almost always, but soldier on.

“It represents the life, the struggle, the maternity of some of us,” said photographer Fatima Rojas, a local immigrant and education rights activist. “The most important part is that we’re women united for art. I really like that. It’s a very diverse group with different experiences, different lives, and together … it’s beautiful.”

That was also Gilbert’s hope for the show—to have New Haveners practicing photojournalism with an ethical lens, instead of “outsiders coming into communities, taking photos and then leaving.”

MULA members Vanesa Suarez, Fatima Rojas and Enedelia.

“The photos here today tell stories that are far more complex and far more nuanced than the images we typically see coming out of mainstream media sources,” she said at the opening.

A senior in political science at Yale University, Gilbert collaborated closely with ULA for the project, arming women with single-use cameras from October 2017 to February of this year. On a semi-monthly basis, photographers got together to discuss their own work, trading stories behind the photographs.

They—referred to by first name only as Fatima, Nadia, Hazel, Vanesa, and Enedelia in exhibition materials— span three generations of immigrant women. They are activists and non-activists, students and teachers, moms and not-yet-parents, married women and single women. What they have in common, Rojas said, are the “kilometers and kilometers of distance between our countries in Latin America” and New Haven, and their collective struggle as they are “faced with a culture that is not our own, some assimilating, others resisting.”

"I know two girls: Dignity and Rebellion/Nothing and no one can detain them."

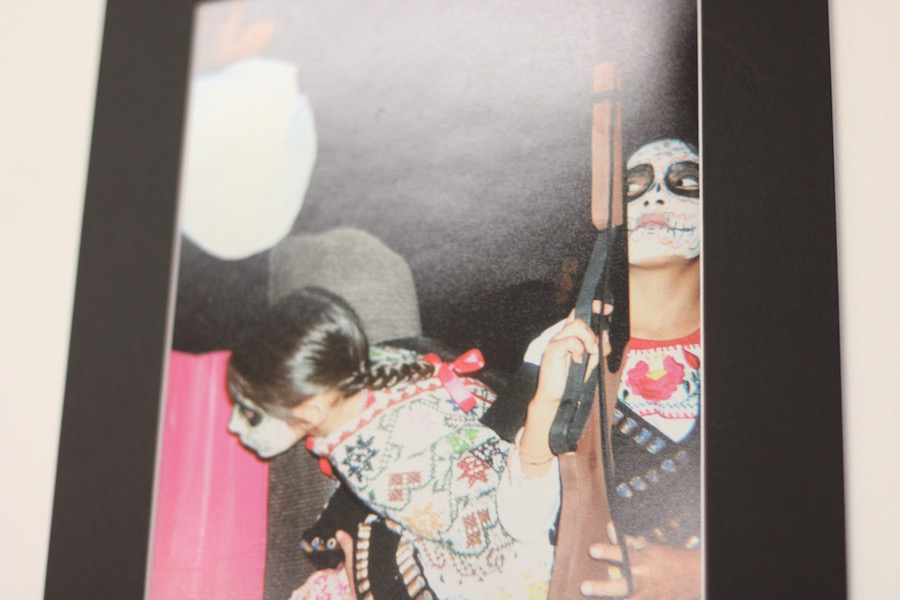

That tension is reflected in the photos, a mix of community portraits and snapshots of private home life, each accompanied by a label in English and Spanish. In several, viewers see behind-the-scenes footage from last year’s Dia De Los Muertos parade, as soldaderas unwind at Bregamos Community Theater, dancing with their scallop-edged skirts, wooden guns and bullet sashes to music somewhere in the distance, muted beyond the frame.

In the low light of that party, Hazel has photographed the mural of Satchel Ramos that was painted after his murder in 2013, with the title Recuérdame (Remember Me). Others have captured a few young soldaderas that remain cautious, cocking their rifles and scoping out the territory, elaborate black, white and green skulls painted across their faces.

“I know two girls: Dignity and Rebellion/Nothing and no one can detain them/‘Neither animal nor police,’” begins a poem beneath one picture, written in Spanish by Enedelia and translated by her partner Joe. “When my heart despairs/and I feel pure rage,/I just remember that the future is theirs.”

"I Have You in My Arms," 2017.

Others are glimpses, intimate yet universal, into private kitchens, bedrooms, family hikes. In one, a mother breastfeeds, her left hand holding her right breast beneath a pink cotton shirt with a spray of sequins at the collar. In her arms, a tiny bundle in white, eyes closed like seashells. There’s a tiny, soft head, a shock of damp brown hair. You can smell his scalp, that sweet and dank smell that belongs to nothing else in the world.

Or Nadia’s Thanksgiving a nuestra estilo (Thanksgiving, Our Way), taken before the holiday last November. At the photograph’s left, a fellow member of MULA mills toasted pumpkin seeds, a sea of brown and white specks in a cast iron skillet before her. From the skillet, they will go into chicken tamales, a taste that the cook has brought to her drafty New Haven kitchen.

“This is important because it makes me proud to give my twist on the celebration,” the label reads. “Something that connects me to my country, Ecuador.”

At the opening last weekend, photographers spoke as attendees piled their plates with homemade chicken, meat and vegetarian flautas, pork- and pea-studded rice, bean and cabbage empanadas. Slowly, they formed a half-circle around the artists, leaning in to listen.

“This project helped me realize the power of socializing with and learning from people from other countries,” said Nadia. “This project aims to get us involved in the community; to demonstrate that we, too, are capable of anything we put our minds to; and in this way, to be heard in our communities.”

“This project was very special to me, because I got to know these women on a much deeper level,” added artist Vanesa Suarez. A portrait of her as a soldadera winked out from a wall. “Through the artwork, we got to have a lot of conversations with very vulnerable women, which I think is part of our program. It’s not a bad thing. It’s a really beautiful thing to share with each other.”

Enedelia, dancing at the opening (there was music after remarks) with one of her two sons. "We are women who practice memory through projects and gatherings, just as our predecessors have done," she wrote in an exhibition booklet. "Through this, we do not forget our roots, our culture."

“As immigrant women, we got to share our experiences—not just what led us here, but what are lives have been like since we’ve been here,” she continued. “How we have changed, and what we bring with us."

One of Enedelia’s young sons rolled a toy train across the floor, attendees crouching down to roll it back. As if on cue, she pulled out a poem in English and Spanish, reading it before attendees went back to looking at the photographs.

She comes from far away, and she remembers the road.

On her back she carries her experience: the rope, the heavy load.

Memories from her childhood, her aching feet and heart

Evenings at the moon she brayed and tore the night apart

However, now this old mule shall never be exploited.

Beware, Mr. Farmer, her savage kick! Avoid it!

La fotografía de MULA is on view at 266 Grand Avenue by appointment only. To schedule a viewing, email Julia Char Gilbert at julia.gilbert@yale.edu.