Jocelyn Pleasant fused and unfused with her balafon, waves of green light splashing on her face. Her hands were flying. Seny Tatchol Camara coaxed a full-lunged phrase, and then another, and then another from his djembe. In front of the stage, feet pounded the floor. Hips sank and swayed. Arms flew up, hands extended, and stayed there.

It was the culmination of Sofar Sounds New Haven, “Welcome to Wakanda” version. Named after the record-smashing release of Black Panther earlier this month, the Saturday night concert drew close to 60 attendees for spoken word, puppetry, and West African Music at a home in the Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills neighborhood of New Haven.

In Marvel’s new movie Black Panther, Wakanda is a fictional country that runs on vibranium, an element with powers that have led to a high-tech, peaceable and completely hidden society. As the country thrives on this resource, descendants of the African diaspora suffer around the globe and on the African continent alike. It’s there that a story of reparations, revenge, and family relations begins, criss-crossing continental boundaries to show how porous they really are.

And so it was fitting perhaps, amidst the rallying cry of “Wakanda Forever!” and South African dark house music, that Sofar would have a concert entirely dedicated to social justice. The series, which will be one year old in April, is no stranger to responding to current events through its music—artists like Mooncha, Manny James, and organizer Paul Bryant Hudson himself have all released pieces that put identity politics front and center.

Organizer Paul Bryant Hudson kicks things off. Lucy Gellman Photos.

But the latest took a deep dive into police brutality and social justice initiatives in New Haven, making a moving case for an improved all-civilian review board (CRB), more New Haven jobs, and better white accompliceship—not simply allyship—through artmaking. A performance with the thesis that, as performer Salwa Abdussabur put it, “without Black Lives Matter, we wouldn’t have all lives.”

After opening the evening with a cover of Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song,” organizer Paul Bryant Hudson handed the mic to Chris Desir, a member of People Against Police Brutality.

“We’re trying to make the police a little less terrible,” Desir said, chronicling the history of New Haven’s fight for a stronger CRB and current advocacy efforts at the Board of Alders. “This is something that people have been working on in New Haven for over 20 years now.”

Pete Greco.

“Given that it’s ‘Welcome to Wakanda,’ I just want to give a shout out to Black women … the Black women who have been involved in this work and pushing this work for the entire time that People Against Police Brutality has existed,” Desir added. “Camille Seaberry, doing the slow grind that is organizing … and also a shout out to Emma Jones, who is an amazing woman and organizer. All the work that we do is made possible by all the work that she does, and is still doing.”

The room exploded in applause, then hushed again as Abdussabur came to the rug-turned-stage at the front. Their blazer flashed white and green in the room’s mood lighting. Pete Greco strummed a few final chords on the guitar as they lowered the mic stand.

“One of the things that makes me feel super comfortable is when people are reacting,” they said to the group. “When people have a visceral reaction. I’m going to be doing poetry, so a lot of things I’m going to say, you guys might feel the need to shout out. It’s about to get a little churchy in here.”

The room broke into low laughter. “In poetry, we snap,” they continued. “Can you try that for me?”

The room filled with a chorus of snaps, like rain drops hitting the roof in musical plinks.

“Yeeees! Yes,” they said. “Now I know that y’all can snap, so don’t be trying to play me.”

On October 20, 1998, Yale-New Haven Hospital

Beautiful Black legs open, my mother birthed her very own statistic

And growing up in a city you learn hard lessons of oppression, lessons

Not taught by a nurturing kind hand but by the land

Let me take you back to New Haven’s modern-day history: Class is in session

Attendees, shoulder-to-shoulder on the floor, leaned in to the words. Some members of the audience closed their eyes, deep and guttural Mmmms coming out like purrs. Others watched Abdussabur’s every movement, snapping as they sank into the poem, swinging from side to side.

Lesson one: You are too gay

Demonized by peers and staff alike

Homophobic administration turned a blind eye—your sexuality an abomination

Stones you with their glares

Pauses, more snaps. Abdussabur was painting a social justice syllabus with their words.

Lesson two: you are too Black to set foot on slave master’s campus

Lest green grass grown by your ancestors shine with negro, stay away

Grown for their eyes, not yours.

Ivory walls protect the naive and miseducated—I mean

most educated people you’ll ever meet.

We are glad you are too scared to walk down Dixwell streets

Then maybe you won’t purge our neighborhoods

Maybe it will delay Yale’s gentrifying feast

Sinking its teeth into properties run down from the lack of jobs given to residents in the city

Keeping young Black boys and girls in the cycle of poverty

The words tumbled forward. Black bodies and minds told that they are nothing but second-class citizens. Yale University, spreading its castle-like fingers over the city’s streets as properties disappeared from the tax rolls. A near-constant lack of jobs for New Haven residents who needed them most desperately.

Lesson three: you are too young

Sound rains through strained red strep throat

Infected with systematic oppression, systematic depression

Of our collapsed lyrics, filled with every bullet that vomits

To another youth’s innocent mind

Watching our peers be shot down,

too many names to count on both hands.

Abdussabur was unstoppable. They barreled toward the end, the crowd hanging on to every word.

You aren’t too Black, too gay, too young to make a change

Where we could be leaders

Without life exchange.

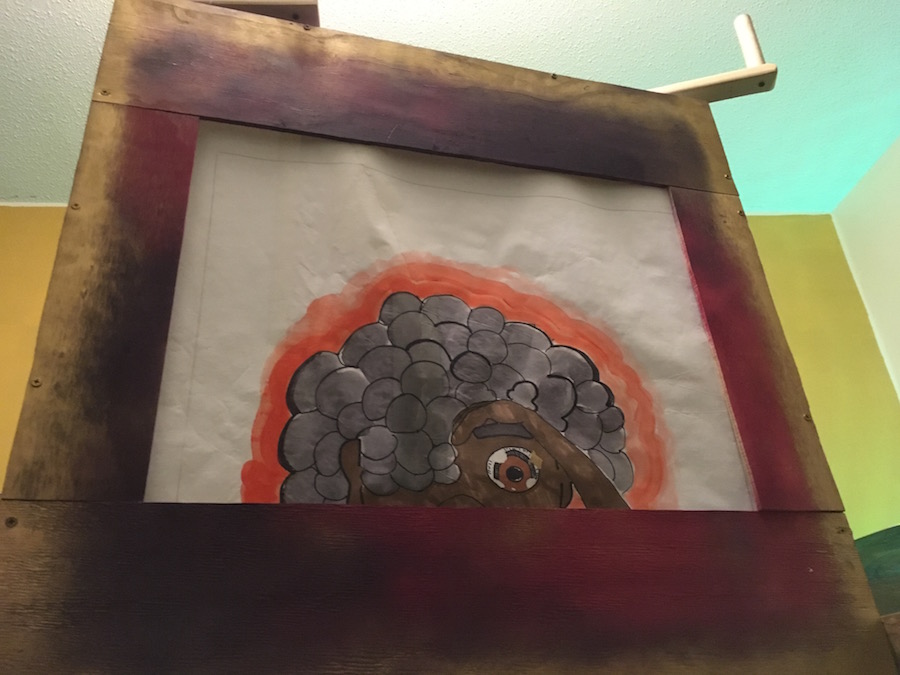

Three poems (click on the sound file above for more) unleashed a heartbeat-like, quiet and elegant fury that kept going with Isaac Bloodworth, a lifelong New Havener who graduated from the University of Connecticut’s Puppet Arts program last year. Pulling a homemade wooden frame onto the table, he mounted a hand-painted, moving panorama titled “Larvae,” part one in his Metamorphosis series.

“Seven years ago on June 1, a king was born into a world that deemed him as less than that,” he began. “Freddy Freeloader” from Miles Davis’ album Kind of Blue clinked and rumbled beneath the words. “He was not only destined to be great, but to commit great acts in the world. This wonderful child’s name was Joy.”

Joy, as depicted by Bloodworth.

On the display, Joy tumbled through his childhood, buoyant and playful. Head of wooly, black hair and eyes that shone bright as they took in the world around him. “His favorite thing to do was go outside and chase butterflies all day,” Bloodworth read from behind the screen. “It always seemed to bring him on an adventure.”

One moment, the little boy was there on the paper, brightly rendered in watercolor. Then he was talking to his parents about racial difference, nodding avidly as he took in their measured warnings about the outside world. The next, he was chasing a gold-and-purple butterfly out of his front yard, across the street, and into the city.

But the farther Joy ran, the more his story left the ballet of childhood. Scenes became too familiar: Joy running into the legs of a police officer who offered him a popsicle, just to post an image on his department’s Blue Lives Matter page.

Joy buying a pack of skittles and tea in his favorite corner store. Joy running into the legs of a junkie on the street corner, who threatened him with a gun. Joy chasing the butterfly to a park, where he pretended to shoot at it with his hands.

“Munching on his skittles, he could hear a siren off in the distance, but … he didn’t think too much of it,” Bloodworth read steadily from behind the screen, his head and feet visible on both sides of the panorama. “But the sirens got closer and closer, and this time he could see it gliding over the blades of grass, crushing them ever so softly. And before he knew it …”

Tracks from Kind of Blue faded into Nina Simone’s cover of Billie Holliday and Abel Meeropol's “Strange Fruit”. A different Joy rolled onto the screen. His hair was a sort of black-purple. Wide, young and trusting eyes had turned the blue and red of flashing police lights. Behind him, the police video of Tamir Rice’s final moments appeared like a ghost, Officer Timothy Loehmann flashing across the screen before killing a 12-year-old boy.

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop

Here is a strange and bitter crop

The room remained completely silent as the last notes rang out, and Joy remained frozen in red and blue on the page. Hudson approached the mic.

“I feel like we need to unpack that,” he said. “How are people feeling?”

Toward the middle of the room, an attendee took a deep breath. “It’s what you’re not expecting and what you’re expecting,” she said. From the wall, New Havener Kenda Payne-Branch nodded knowingly. A mother of two boys, she said she fears police brutality in not just her own life, but the lives of those around her.

“Nobody should have to bury their child,” she said.

“To see it again it just stirs up that disbelief and that anger that we’re back to being in a place in society where our kids are not safe,” she added later of the video. “That’s scary as a parent to sit back and know that you can’t help. It gets beyond a point where you can say: ‘Listen. I love you, I’m here.’”

That’s a story Bloodworth has encountered firsthand. During his time at UConn, he told the room, he dealt with white students attempting to tell him that racism wasn’t a real thing. He had professors who’d never considered teaching a Black student in puppet arts and mask-making, and found themselves stumped on lessons of “flesh tone.”

He recalled epithets thrown at him from all sides of campus, and the difficulty he faced as the only Black student in many of his classes. He spoke about trying to form a Black men’s group on campus, only to be told that white men should be allowed in as well, as not to discriminate. In the end, he and other Black male students lost the fight.

The freshness of the story still reverberating through the house, Middletown-based The Lost Tribe took the stage as the final act of the evening. A six-piece group with flute, sax, guitar, trombone, drums and balafon, they brought West Africa to New Haven, filling the first floor with sounds birthed by the Mali Empire and African diaspora.

Attendees made space for a dance circle, yielding the floor to each other as rhythm hammered through the floor. Organizer and host Raven Blake kicked the circle off, bowing to the players as she danced. Towards the back of the crowd, poets from The Word formed a circle of their own, members dipping in and out to freestyle as the music shifted, heavy on the brass.

Earlier in the concert, Hudson had gently teased attendees who hadn’t yet made it to Black Panther. Now as the night wound down, he said he was almost done with the requisite Wakanda-shaming. Almost.

“But really,” he said. “Go see the damn movie.”