A teen diving deep into a parenthood that was love and pain. A student who wants New Haveners to get more woke. A balladeer embarking on a story of self-love. A poet who had lost her voice but not her words, and was determined to finish her poem.

Thursday afternoon, these voices joined over 10 others at a semiannual creative writing reading of students at Cooperative Arts and Humanities High School on College Street. Organized by creative writing department chair Judi Katz, the reading featured young poets, fiction writers, and playwrights who are studying creative writing with teachers Katz, Mindi Englart, and Aaron Brenner. An encore was held at 6 p.m. Thursday evening.

Students have been rehearsing with Katz, a poet who studied acting in college. In her class, she said she sometimes blocks off time for practice runs. Then students were supposed to get to the main stage on Wednesday—which didn’t happen because New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) called a snow day. She said she’d squeezed in an extra rehearsal Thursday morning.

“The primary aspect of that practice is getting them to slow down,” she said. “I mainly tell them: You want to hear the work. You want to give it its due.”

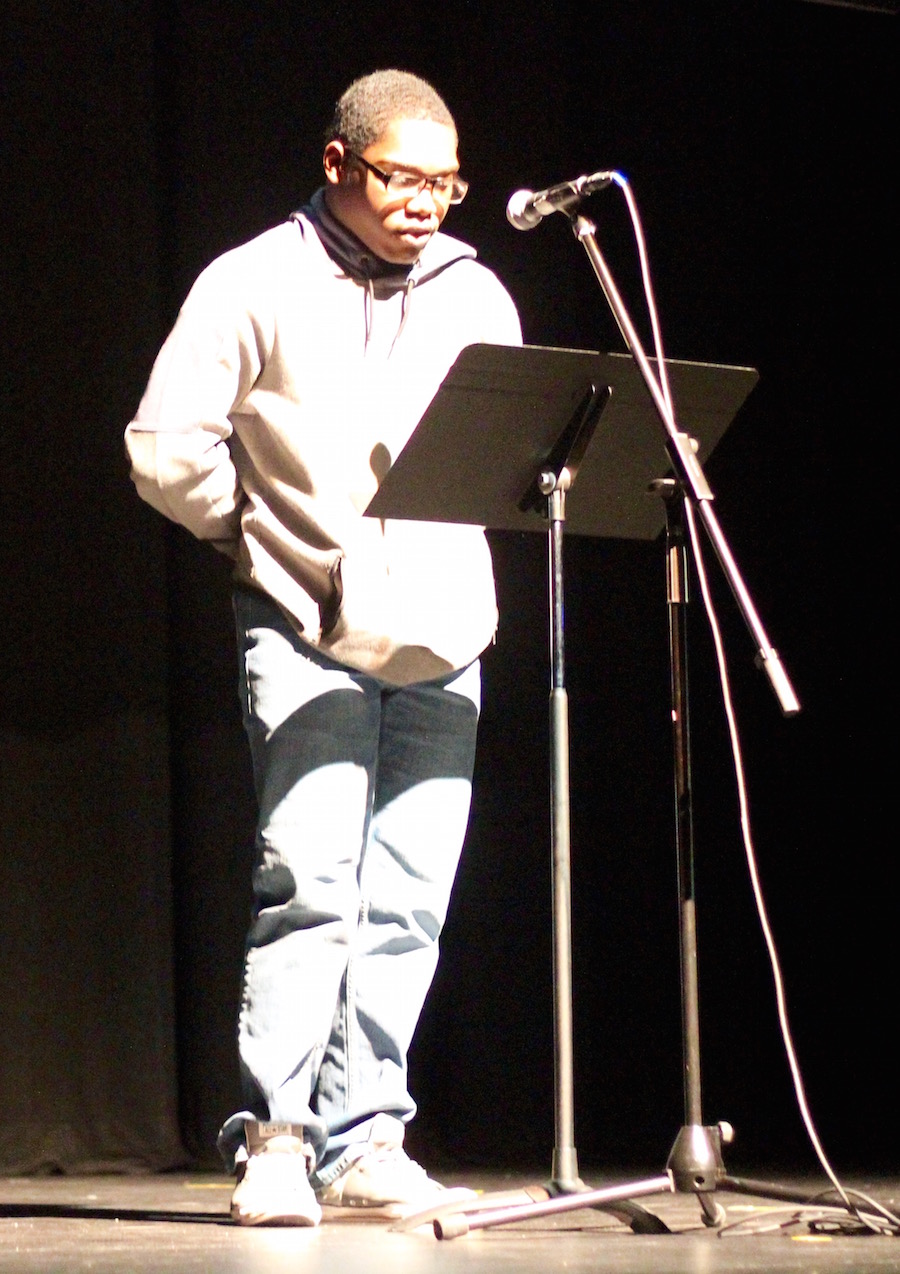

Marquel Woods: "Why did you have to set me free?" Lucy Gellman Photos.

That was true for 17-year-old Marquel Horton Woods, whose mother Shaneka was struck and killed by a motorist last September. Woods hadn’t had an easy relationship with his mother, he said after the reading. They had loved each other deeply, but “she had her issues and I had mine … they didn’t always combine.”

He said he hadn’t been prepared to lose her suddenly. Once he started processing that grief, he’d found that a poem was knocking at the front of his skull, trying to make it out. He listened to it, committing the words to paper.

“I am free from the past/and being trapped/in your suffocating gravitational pull/constantly reminded of our madness,” he read on Co-Op’s bright stage, quiet and sure as he spread his feet slightly. “Me using madness to face you daily/And you using it to live with itself.”

His classmates, dotting the first few rows, leaned in.

“I am free from the constant confrontations/The corners you would back me into/Screaming at my face and bulking my forehead/trying to escalate the situation/and push me far beyond my breaking point.”

He was free, he continued, from his mother’s “guilt-ridden projections,” her verbal abuse that infected their home, his fear of her breaking down in public. But also “free from your constant love/from the feeling of someone caring more for you then for themselves.”

Which was to say, he told the audience between each line, that he was not free, but still grieving.

“Why did you have to set me free?” he asked, voice steady on the words. “Freedom took away my pain./Freedom took away my innocence./Freedom took away my strength./Freedom took away my mom./And I don’t want to be free.”

As he stepped out into the bright hallway after the reading, he squinted for a moment, readjusting to the light.

“This was the hardest piece that I’ve ever had to write,” he said.

Jamih Green: ‘Stead of staying motivated, want to stay out in the streets/And they’re hurting other people so just that they can feel unique.

He was among a handful of students to approach loss through their words. Jai’dyn Johnson held the room with her short, moving “Dear Uncle Jamie,” to an uncle she had recently lost. Erica Cardona mourned the loss of a great love. Jamiah Green critiqued the violence she's seen as "a girl who grew up in the hood," drawing the first whoop whoops of the afternoon with her poem “Society Today.”

Why is it that there are so many people who don’t wanna hear the truth

Got the tears in their eyes from the lies that they’re letting through

And I will tell them that the truth will set them free

But they let the lies give themselves a hold ….

‘Stead of staying motivated, want to stay out in the streets

And they’re hurting other people so just that they can feel unique

But don’t you know the pain that you’re causing for others

The pain that you’re causing the father, the mother?

There were pieces geared toward Black history—not the month, but general history—that remained overlooked in classes. With her poem “Never Forget Her,” Mellody Massaquoi painted the life of 16th century African Queen Amina, who led troops into battle and began trading with the Middle East before her death.

“The problem is that in America, we aren’t told stories of African queens,” she read. “When it comes to Africans or African Americans, the only stories we hear are about the slaves and Martin Luther King, Jr. Black history is slowly being forgotten and it shouldn’t be.”

Mariah Dillard kept the momentum going with her poem “Woke” with a blown-up drawing of Daveed Diggs projected in the background, his wet, soft eyes staring out above her words. Throughout the show, images like this from Co-Op’s art magazine Metamorphosis 2017 popped up on a projector.

“Girl you are too damn woke,” she read, looking out at the audience with a half-smile. “Sound like a bunch of Twitter tweets you never wrote. You are a joke. Prancing around in your Black Lives Matter tee all because it is trendy? Girl, please.”

“I don’t think you understand how unique the skin that you in can be,” she continued. “Do you really know what woke means? We’re not included in most of the stuff we fought for.”

It wasn’t the first time she performed the poem, and it wouldn’t be the last. As she headed out into the hallway, she ran into Assistant Principal Mark Sweeting. Pulling out her phone, she showed him a practice video that she’s taken beforehand. At one point, he gave a little shout, and then clapped for an audience of exactly one.

Just 30 minutes before, Dillard had watched as the reading had unearthed a dozen new stories, from ballads of longing to a short play about a student’s dead dog, Harold. Nadia Gaskins opened her ribcage to everything inside with her piece “Broken-Hearted Girl.” Ana Lujan took a trip down memory lane, transforming into her childhood memories before the audience.

With her poem “Awareness,” Kayla Velasquez found her voice after literally losing it, a frog in her throat as the words sprang from the page. “I am as real as I could possibly be,” she read, undeterred as her voice shorted.

Testing the duet style, Zanei Buchanan and Charlie Brown debuted their poem “sleep,” placing themselves on parallel sides of sleep and wakefulness, joy and depression.

“I’ve never had a nightmare,” Buchanan began.

“I’ve never had a dream,” Brown took over.

“Only things that make me count the seconds until it’s time to sleep,” Buchanan took over.

“Only things that make me count the seconds until it’s time to wake up,” Brown countered.

“Bluebirds singing in the trees,” Buchanan returned, rolling out a pastoral image.

“Buzzards calling in the road,” Brown read.

“Light falls from clear skies,” Buchanan came back.

“Rain falls from dark clouds,” Brown.

A gentle breeze combs through the grass,” Buchanan.

A violent wind unearths the grass,” Brown rumbled.

“Will I ever wake up?” they both asked aloud.

After the reading, Englart and Brenner milled around at the back of the auditorium as students filed out to a Black History Month Dinner.

“It’s really tough what they do,” Brenner said. “In the theater, people have scripts. Musicians have music. Dancers have choreographers. This is their own work. I think that’s hard! I think just getting up there is pretty darn brave.”

“Our school has a big performing arts bent … this is the quiet art,” added Englart. “This is their own work. It’s personal, more vulnerable, and when they do it, it’s a great equalizer.”

To listen to audio from the reading, click on the audio player above.