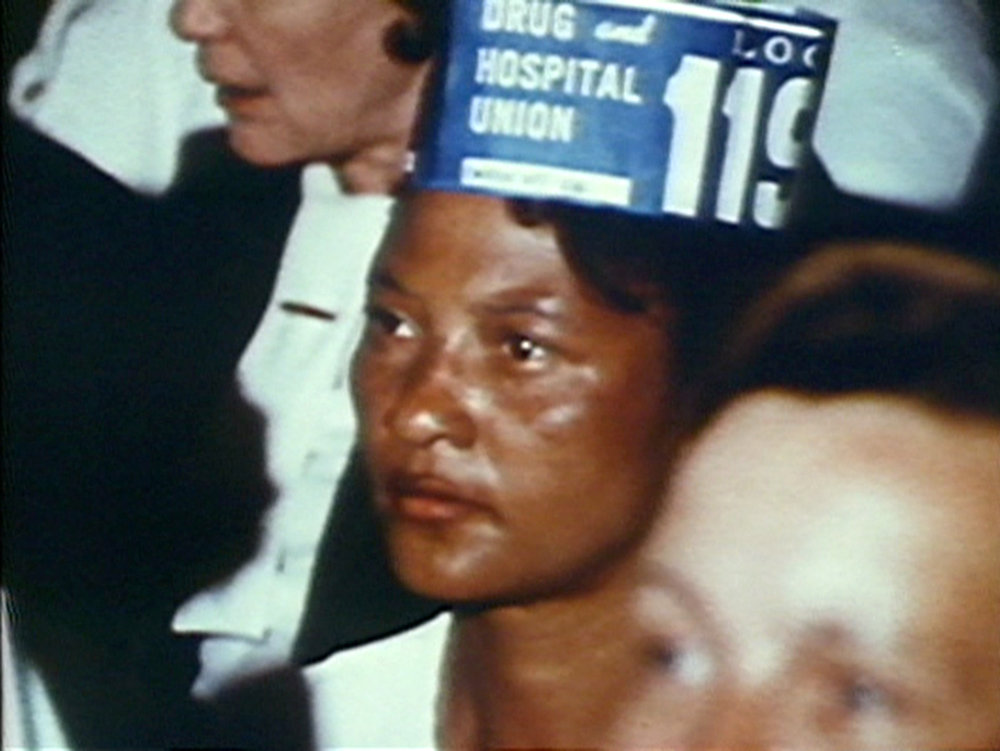

Still from Madeline Anderson's 1970 documentary I AM SOMEBODY.

In March 1969, 400 nurse’s aides, housekeepers, and cooks at the South Carolina Medical College Hospital went on strike. Almost all of them were black. Almost all of them were female.

For the next 100 days, these women marched through the streets of Charleston, South Carolina, singing civil rights songs, holding nighttime protests, and decrying the low wages, heavy workload, and vicious racial discrimination that had driven them from their workplace.

Before they went on strike, many of these women made as little as $1.30 an hour. The nurses called them “monkey grunts.”

I Am Somebody (1970), a thirty-minute documentary from director Madeline Anderson, chronicles the nearly four-month standoff between the striking hospital workers, organizers from New York’s Local 1199 hospital workers union, and civil rights leaders from the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) on the one hand, and, on the other, the hospital administration, the South Carolina governor, and the National Guard.

Coming just a year after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tenn. in April 1968, SCLC’s leadership in the strike represents a potent reminder of the civil rights organization’s sustained commitment to desegregating the South even in the wake of the tragic loss of its leader.

Anderson’s camera follows SCLC stalwarts Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young as they preach to and mobilize both the striking workers and the poor, black Charleston communities in which they live. Coretta Scott King, wearing a blue-and-white paper 1199 union hat, tells a crowded church full of striking workers that she believes that the black woman faces more discrimination than any other American in the workplace.

And yet, true to its self-affirming title and cinéma vérité documentary style, I Am Somebody is first and foremost about the courage of the women who had no national profile, who had everything to lose when they walked out of their jobs and demanded fairer treatment.

The movie opens in historic Downtown Charleston, where hordes of well-to-do white tourists visit Ft. Sumter and nostalgic Confederate Memorials. An unidentified female narrator says that, in 1969, these tourists saw more than just paeans to the state’s racist past; they saw poor, black men, women and children protesting in the streets, demanding equal treatment. They saw Charelston as it really was, at least if you were poor and black.

“We, as black people in South Carolina, have awakened to the fact that we are no longer afraid of the white man,” the narrator says, “and that we want to be recognized. Not because of our race, but because we are human beings.”

There are no talking heads in this movie. There are no experts witnesses or guides to help the audience through the strike. There are just the women, showing up in force in blue-and-white union hats, singing in the dark in defiance of the governor’s curfew, getting shoved into the backs of police cars for peacefully protesting and “disturbing the peace.”

Much like landmark vérité documentaries like Frederick Wiseman’s Hospital (also made in 1970), I Am Somebody keeps its camera, and its story, trained on the scores of relatively anonymous working people who work together with great ability and determination to create something larger than themselves: a powerful social force, a movement.

Halfway through the documentary, the strike extends beyond the strikers themselves. Anderson shows Abernathy imploring local students to skip school and stand on the picket lines with their parents and brothers and sisters. The students, no older than middle school or high school, rally in the parks downtown, demanding higher pay and better treatment for the hospital workers.

Late in the movie, the narrator says that SCLC brought the soul power and 1199 brought the union power. True enough, watching the women organize for racial and economic rights, one can’t help but think of King’s clarion cry that racial justice cannot come without economic justice. One can’t help but remember that he was killed while helping Memphis sanitation workers organize a union in response to poor wages, dangerous working conditions, and persistent racial discrimination.

Although a New York transplant from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, Anderson spoke often about how she so easily identified with the hospital workers on strike. Anderson left a career as a teacher to pursue filmmaking at NYU. She wanted to join the editor’s union, since getting a job in the film industry was virtually impossible if you were not in a union. The Catch 22 was, of course, that you often could not get a job if you were not in a union.

Not until director Shirley Clarke took Anderson on as an assistant director for the 1963 drama The Cool World was she able to join the editor’s union. Even then, she found it exceedingly difficult to get any kind of distribution deal for I Am Somebody, as most studios saw little market potential for a movie about poor black women in Charleston, South Carolina.

Watching I Am Somebody today is a reminder of the lengths that courageous and determined people will go to to secure an incrementally better, fairer life for themselves and their communities. The women didn’t win a union at the end of the strike, but they did win concessions: all of them were rehired without retribution; the employer agreed to a six-step grievance process; many received modest pay increases.

But the legacy of the strike and the story and images of I Am Somebody is an achievement that goes beyond the specific concessions of a particular employer. At the end of the film, one of the leaders of the strike is asked what the hospital workers accomplished through their months’ long protests.

“Well, are now treated a bit more like people,” she responds.

This review is part of a series of Black History Month movie reviews in collaboration with the "Joe Ugly in the Morning" radio show. Tune in to WNHH Community Radio every Monday at 8:15 to catch a new review of a current or classic movie about African American life.