Culture & Community | Food insecurity | Food Justice | Food Rescue U.S. | Greater New Haven | Lori Martin

Lori Martin: "It troubles me every day that there is being food thrown away and we have people that could use food. That match we all can make together." Lucy Gellman Photos.

Lori Martin: "It troubles me every day that there is being food thrown away and we have people that could use food. That match we all can make together." Lucy Gellman Photos.

Ryan Cosgrove has a special routine at Liuzzi Gourmet Food Market twice a week. Working his way between fresh meats and narrow shelves of salad, pasta, and prepackaged meals, he begins packing whole boxes methodically. In go the loaves of bread, sandwiches, fresh produce, pasta salad that is one day away from expiring. The perishables fill up at least one box, but sometimes as many as three or four or five.

But it’s not part of the shipping North Haven-based Liuzzi does around the country. It’s to fill hungry bellies as food insecurity rises across New Haven and the state, and state dollars fail to fill a growing gap.

Cosgrove is part of the New Haven chapter of Food Rescue U.S., a national organization that pairs supermarkets, bakeries, and specialty food stores with organizations in need of food. Each week, food providers with excess product send their food to pantries, religious organizations, schools, daycare and outreach centers that serve food insecure individuals and families. And they have a network of local volunteers to do it.

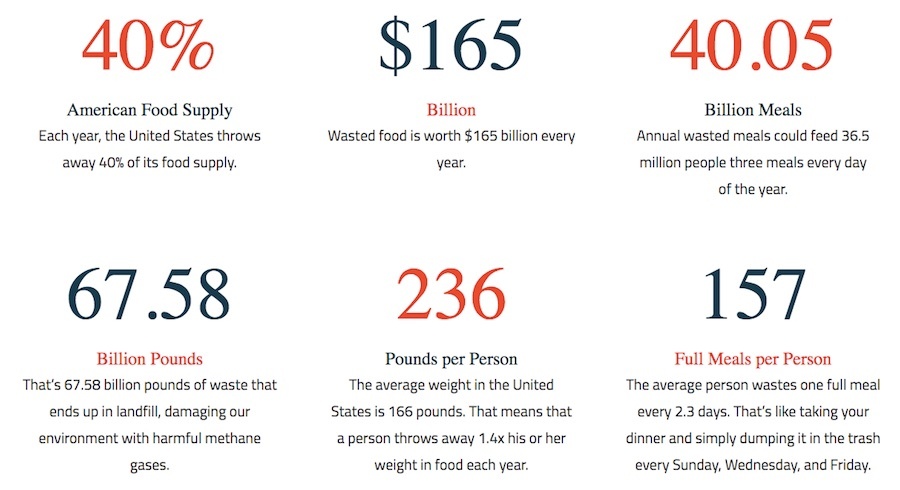

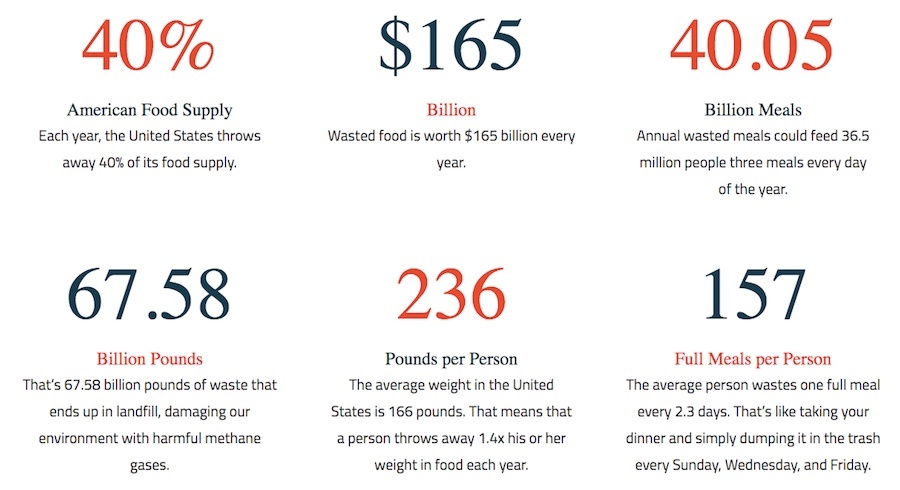

It’s an intended solution to a common problem, said Food Rescue U.S.’s New Haven Site Director Lori Martin in an interview for WNHH Radio’s “Kitchen Sync” program. There is a huge amount of food waste each day in the United States—40.05 billion meals per year, according to the organization’s data. In New Haven, food insecurity has reached staggering highs: 22 percent overall and 34 percent in low-income neighborhoods, up from what it’s been in past years.

At the same time, grocery stores and bakeries are dealing with food they can’t sell, but don’t want to throw away. Sometimes it’s yogurt too close to its printed expiration date. Or maybe it’s a loaf bread that hasn’t sold, and will be stale by the next morning, but could go to use in someone’s dinner that night. Or a bag of 15 clementine oranges, with just one that is bruised.

“Employees or managers are concerned that there’s extra food,” said Martin. “They know that this food is worthy of being eaten, but it’s past its sell-by date. They’re in touch with us to say ‘Hey, how can we work on this program to get it done?’”

That’s where Food Rescue’s network of volunteers comes in. Using an app that lets them know who needs a pickup, they identify community partners in need of food aid, and then drop food off at those sites. The app lets them be responsive to the speed of turnover—that some food only has an hours-long lifespan between pickup and the time that it’s eaten, and will go to waste otherwise.

Martin: "I do tell donors that I can take food at the end date when they can’t sell it, but people can be eating it. Often the food that we rescue is eaten within a day or two once it gets out to folks who need it. So we can take it at the sell-by date because it’ll be consumed so quickly."

Martin: "I do tell donors that I can take food at the end date when they can’t sell it, but people can be eating it. Often the food that we rescue is eaten within a day or two once it gets out to folks who need it. So we can take it at the sell-by date because it’ll be consumed so quickly."

“I can get calls and sometimes texts … and then I’m able to stick it out on the app, let folks know that there’s a run that needs to happen in a few hours,” Martin said. Occasionally the app gets buggy, when is when Martin “runs and gets in the car, just me and my kids ourselves, and move it.”

There are still bugs in the system, but they’re getting smaller. Martin noted that large institutions like Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU) have reached out, expressing interest in donating their extra food on a daily and weekly basis. So far, New Haven volunteers haven’t been able to handle a load that large.

Food Rescue As A Life Choice

Data from Food Rescue U.S. national website. Courtesy Food Rescue U.S.

Data from Food Rescue U.S. national website. Courtesy Food Rescue U.S.

Long before Food Rescue U.S. captivated Martin, there were the whales. Growing up in New Haven, she learned during kindergarten that whales were being slaughtered from the national nonprofit Save The Whales, and started a letter-writing campaign to her legislators. Her family members split on the issue—some lauded her for it, while others told her she was wasting her time. But the act—“I was an early writer, then,” she recalled—ignited a fire in her.

From whales, she developed into a self-described “lifelong environmentalist—including humans.” She began looking closely at the world around her, growing quietly angry at what she saw. She watched as then-president Ronald Reagan spun the myth of the welfare queen into being, and worked on fighting it at every chance she got.

“It was the one I think I felt the most infuriated by,” she recalled. “I was born here … and I was still living here as a high school student, and was traveling from one side of the city to the other to go to school, and saw folks really struggling and working hard.”

“I was an anomaly,” she added of her life at home in those years, a laugh catching in her throat. “We [my parents and I] don’t share the same political views. But I came in the world with a different understanding, and a different place in my heart for people.”

Martin's son on a food rescue mission. Food Rescue U.S. Photo.

Martin's son on a food rescue mission. Food Rescue U.S. Photo.

She was captivated as she watched New Haveners from each neighborhood in the city become civically involved, “committed to making the city a better place to live.” From high school activism she went on to college in Arizona, then education, and renewable energy.

Then in the early 2010s, Martin signed up as a volunteer with Food Rescue, then called Community Plates. The runs were small: a loaf or two of bread that needed to be shuttled across town. She stayed with it for a while, But then the organization’s director left, and “I got busy with other things.”

For a while, at least. In mid-2015, one of her sons was taking a gap year before college, and Martin encouraged him to “go do something good for the world.” The two were standing outside of a grocery store when he suggested that that thing could be food rescue on a larger scale. They reconnected with the organization, and began doing runs from grocery stores, adding Stop N’ Shop and Trader Joe’s to Food Rescue’s New Haven wheelhouse. Just a few months in, Martin stepped up as director.

“These are conversations that we’ve had forever—how the world moves resources, or hordes them, or doesn’t share them, and food is part of that,” she said of her kids, three of whom now help her with weekly food runs. “Over and over again, their eyes are opened. They see food whatever they are that’s being wasted that they’re shocked by.”

She’s redoubled her efforts in the past year, as demands for food have become higher and more frequent.

“I felt the rise of anxiety around food and kids having food over the last year,” said Martin. “Even since the federal administration changed—before we began to say ‘Hey, food insecurity is rising here in New Haven,’ I could already feel it. I was already hearing more, and people were more concerned. Sort of like, the news came last.”

She’s had success stories, like a city official who passed Whole G Cafe last year, and noticed that it was throwing its leftover bread and baked goods into the dumpsters behind the shop. When the official told row cafe about Food Rescue, employees were quick to redirect their leftovers to the organization.

Or seniors, who have tried fresh, not grown-in-Connecticut foods for the first time through their rescued meals. Last year, a community elder reached out to Martin with some news—she had tried a pomegranate through the program. And it was opening up whole new worlds for her.

“We talk about people needing education—the poorest folks who are getting SNAP benefits and nutrition education,” Martin said. “Actually I think they just need access to good food. If it’s available and it’s affordable … they’ll eat it.”

Or a Head Start program that the program’s now been serving for two years. When Martin brought it onboard in 2016, she watched as some parents shied away from taking food, saying that they weren’t needy enough to bring it home. Then they became more comfortable with the program. Now, she watches as parents “who wouldn’t otherwise have this fresh food” take a bag or a portion of a bag home, and rests easier knowing that the kids will be fed for the night.

“I want to create a new existence for all of us,” she said. “Nobody should be hungry.”

What A Rescue Looks Like

Myles Anderson: “You gotta give back. You won’t believe how many people appreciate having a meal.”

Myles Anderson: “You gotta give back. You won’t believe how many people appreciate having a meal.”

To ensure that she’s fulfilling that mission, Martin works each day matching volunteers—sometimes herself, with a car full of food—with food donors and recipients. She’s learned how to make it into a regimented science, where volunteers scurry in and out of kitchens and markets, grab their bags or boxes of food and head on to the receiving organization.

On a recent Friday morning, Cosgrove was bracing for that minutes-long interaction, checking the market’s window and back door for the arrival of weekly volunteers. Born and raised in the New Haven area, Cosgrove recalled sitting around the dinner table with his family as a kid, and noting an extra seat for anyone who was hungry for the night.

On Thanksgivings during his childhood, his family would volunteer at a soup kitchen in New Haven, his parents trying to teach the family about the importance of feeding those who might not have food. So when Martin struck up a conversation with him about Food Rescue U.S. on a trip to the market last year, he jumped in to help.

Cosgrove: “Why not do something good with it?,”

Cosgrove: “Why not do something good with it?,”

“Why not do something good with it?,” he said of the market’s extra food, adding that Liuzzi often has prepackaged green and pasta salads, fresh sandwiches, and mid-sized dinners that reach their sell-by date but are still good. “Any time you’re feeding someone hungry and less fortunate, it’s worth it. I grew up in an open home, where anyone who was hungry got a meal.”

A little past 10 a.m., Cosgrove looked up and motioned to the back door. “There they are,” he said. Myles Anderson and two volunteers from Hamden-based Autism outreach nonprofit Opportunity House walked in, ready for their pickup.

There two days a week, Anderson moved like clockwork, almost balletic as he took a single box from Cosgrove (it’s usually more food, both he and Cosgrove said) and headed back out to his car. Loading the box in with volunteers Oscar and David, he hopped back in, and prepared for a drop off no more than 15 minutes away.

On Fridays, the group from Opportunity House delivers to The 180 Center, a Christian outreach center on Grand Avenue. The food goes directly to attendees who are food insecure. On Wednesdays, they take food to Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) in East Rock.

As he drove, Anderson said that he’s thrilled that Opportunity House has paired up with Food Rescue U.S.—not just for the organization’s sake, but also for his. A dad of three, he and his wife try to spend each Christmas at a food pantry or charitable organization in Hartford, trying to teach their kids the value of community service.

“Everything now is take, take take, me, me, me,” he said, gripping the wheel as he drove back into New Haven from the market, and turned onto Grand Avenue. “You gotta give back. You won’t believe how many people appreciate having a meal ”

To listen to WNHH Hosts Lucy Gellman or Tom Ficklin interview Martin, click on or download the audio above.