“When I seroconverted I had a rush of emotions, and the best way to process it for me ended up being painting,” said Jonathan Joseph Ganjian at the opening. Detail of Inside pictured above. Lucy Gellman Photos.

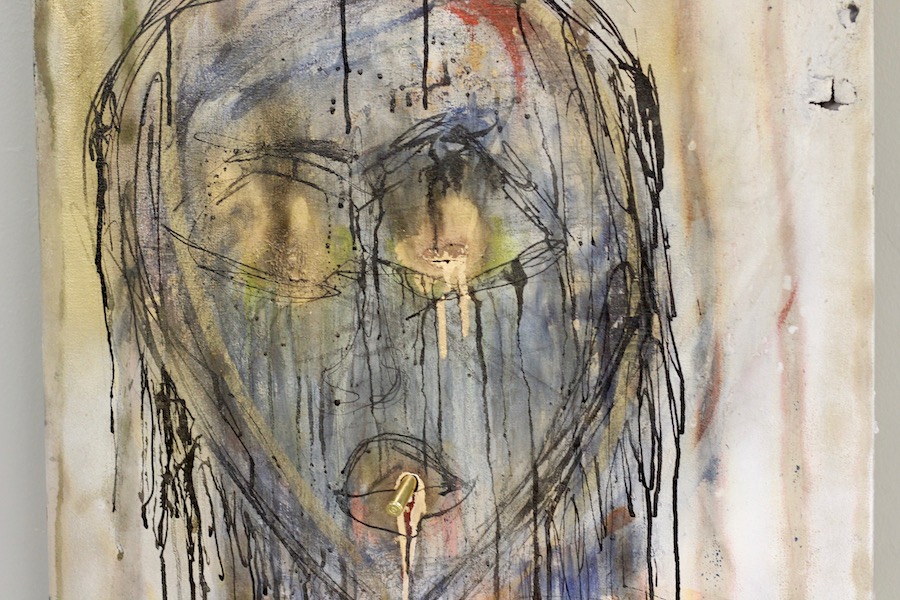

It’s definitely a face, but of more than that, you cant be sure. Something has turned the skin blue. Long, limp black tendrils hang at either cheek, flow over the forehead, nose and lips, running thickly under one eye. Both eyes are closed, lids jaundiced and encircled with green fuzz, as if they have started growing mold. Towards the bottom of the canvas, the lips are punctured by a bullet that glints in the light, just a little off center. It seems, maybe, that the face, unmoving and unmoved, has closed itself to us.

Titled Inside, the painting is one of the works in Facing The Virus, a one-man exhibition now up at the New Haven Pride Center’s (NHPC) basement gallery through April 30. Painted, curated and installed by Jonathan Joseph Ganjian, the show has related programming throughout the months of March and April at the NHPC’s Orange Street digs.

The artist at an opening reception earlier this week.

Works come from Ganjian’s The Gold Series, a multi-year, 50-painting exploration of HIV and AIDS both globally and across the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender (LGBT+) community. By taking that broad lens, the artist said, the series seeks to show the many sides of, and people affected by, the virus. While not all of the work is highly personal, its origin story is— Ganjian seroconverted in 2010, and began the series around late 2013.

“When I seroconverted I had a rush of emotions, and the best way to process it for me ended up being painting,” said Ganjian at an opening reception earlier this week. “After a few paintings in, I said: You know, maybe I should turn this into something. Maybe I can use this as a platform to talk about a lot of things that are difficult.”

Difficult things like HIV in prisons, which he puts front and center with Inside. After Ganjian’s seroconversion—the term that marks the earliest detectable stages of an HIV infection—he began personal research into “the twisted story of HIV behind bars.”

As he dug ever deeper, he learned that LGBT+ prisoners were several times more likely to be raped, abused, sexually assaulted, and denied access to anti-retroviral medication while incarcerated. In 2016, he was 30 paintings into The Gold Series, ready for a break from it, and had just started Arête, 10 paintings based on trauma that he had not personally lived.

When he finished Arête and cycled back to The Gold Series “with new eyes,” Inside was beckoning to be made.

As he worked on the canvas, “I wanted a springboard or a platform to talk about the effects of incarceration and prison culture for those who have HIV.” A bluish face emerged, that Ganjian’s streaked with color until it seemed bruised and busy, almost too much for itself to take. An exhausted face, eyes closed to the questions viewers might want to ask. A face that has been robbed of something. Near the end of the process, he used fire to temper the image, and punctured the canvas with a bullet at the lips. A hole formed around it, a tiny, shattering crater.

Or Kintsugi, which the artist said is titled for the Japanese process of filling pottery cracks with gold, “celebrating the fault or the flaw or the issue.” In a streaked sea of gold, a whitish specter emerges, close enough to the side of the canvas that it seems it has been walking there this whole time. Then another, on the opposite side of the canvas.

For Ganjian, the piece is about disclosure of one’s diagnosis, particularly in relationships, he said. But around the canvas swirl other references: A reminder of the past or harbinger of things to come, a friendly or not-so-friendly ghost, greeting the viewer as they look at the work for the first time. It could be a set piece in Tony Kushner’s Angels in America, as it returns to Broadway for the first time in 25 years this month.

There are works like The Last Child, which take a broad lens on HIV and AIDS by pivoting to Africa and Southeast Asia, where the virus is often transmitted from mother to child. In the painting, the child in question is anonymous, any hint of a face smudged as blue, pink and tan swirl around a head-shaped orb. The figures shoulders are deep red and black, like they are bleeding early in life. Gold circles fill the background.

Ganjian said he usually works at a larger scale.

Ganjian said there are contemporary giants sitting on his shoulders, naming painters Cy Twombly, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Clyfford Still and Gerhard Richter among his most formative influences. For him, the paint-splattered ghosts of those men have let him open a conversation that wouldn’t work in another genre or medium. At least, not for what he’s trying to get across.

“I think that contemporary painters allow us, as almost no painters before, to really talk about granular deep things at the same time as we’re talking about very vague, abstracted things,” he said. “I think for HIV and AIDS awareness in particular, abstraction gives us a vehicle to drill down into the different areas in which we are operating as activists.”

“Abstraction enabled me to deal with so many areas of living with the virus,” he added. “I knew that if other people, if they looked at this abstract thing and they just felt this raw emotion through abstraction and color theory that they too would say: Oh my god, I’ve been there. Like, I can’t explain why I’ve been there, but I’ve absolutely been there.”

MPowerment Coordinator Richard Duhaime and APNH's Kyle Rodriguez at the opening.

Gliding slowly from painting to painting at the reception, NHPC Director Patrick Dunn said he is particularly excited to have the works up as a current conversation piece on HIV and AIDS. In the next months, he said he is hoping to collaborate with AIDS Project New Haven to bring a group in around the works.

“I think this is a fresh, interesting, now take on the conversation of HIV and AIDS,” he said. “Oftentimes those conversations are very stuck in 80s and 90s experience perspective, especially when it comes to the LGBTQ community.”

“Having artwork on the wall that is very raw emotion and clearly very intense gives us the opportunity to have conversations on a daily basis … the conversation happens naturally because it’s in front of you,” he added. “And I’m looking forward for the ways that we can take this and bring it into the community in a different way.”