A detail from Violence No More , which will be sold in pieces at the end of the show. Proceeds from the piece, and the entire exhibition, will go toward Planned Parenthood of Southern New England. Lucy Gellman Photos.

A detail from Violence No More , which will be sold in pieces at the end of the show. Proceeds from the piece, and the entire exhibition, will go toward Planned Parenthood of Southern New England. Lucy Gellman Photos.

There’s a doll’s head, painted to the color of silver and ash, where the towel rack should be. She seems at peace: her eyes are closed, delicate lashes a chrome color. Her pigtails hang under her like parachute strings. Around her is a web: other children, painted, gilded semiautomatic weapons closer to the back, near the window.

But Violence No More, an installation of painted children’s toys by local artist Margaret Roleke, is meant to take over this bathroom in its sprawl of pinks, grey, yellows and blacks. With 149 other objects, it is part of the second annual Nasty Women New Haven exhibition, now at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art on Trumbull Street.

Titled “Silence Breakers,” the exhibition opened formally Thursday night for International Women’s Day, and will run through April 4. Hundreds attended the three-hour opening.

McClure at the opening.

McClure at the opening.

This year, the exhibition was organized by Nasty Women New Haven co-founder Lucy McClure, with help from an army of nasty women in New Haven and the greater New Haven area. McClure said organizers started planning the exhibition just a few months after last year’s inaugural show, held at the Institute Library’s downstairs space on Chapel Street.

After thousands attended the opening last year, MClure and Artspace New Haven curator Sarah Fritchey planned an entire month of programming to accompany the show. Proceeds from the exhibition and events will go entirely to Planned Parenthood of Southern New England this year.

“This is something that doesn’t exist otherwise,” McClure said at the opening. “This kind of work doesn’t happen in New Haven. It’s not happening in Connecticut. I think there are very few places where everyone, regardless of their class, their socioeconomics, they can come into a single place and share their opinions, their passions. To just feel like it’s okay for them to be there.”

“I’m so tired of seeing the same 20 artists,” she added. “Where are the new artists? We need more opportunities for people to feel like they are not outcasts. To be able to develop that kind of platform for every single human being to be accepted, even through something as simple as the arts, it shows how important the arts really are.”

Details from Elizabeth Antle's woodcut series Dream Home.

Details from Elizabeth Antle's woodcut series Dream Home.

Throughout the house, McClure and an install team have tried to live out that mission, packing every square inch of the building (and some of its backyard) with multimedia work in painting, poetry, sculpture, folk art, installation and video. At each turn, sharp-walled corner, and hallway, works beckon, giving hundreds of definitions on what it means to be a nasty woman almost two years after the term went viral.

Like She and I, a video-sculpture installation by Educational Center for the Arts (ECA) students Aliya Hafiz and Jahnise Bennett. Installed in a low-lit, spacious gallery on the Ely House’s first floor, the work stretches out, filling the entire room with white, raised domes as a video flickers over everything, casting them in a haunting hue. It’s like a maze you’re not sure you can walk inside: the pieces on the floor seem too precious, too precarious to get too close to.

But once you’re in the thick of them, video of eyes and water hurtling toward you at the same time, they’re objects for exploration, things you want to define and cannot quite find the words for.

Margaret Roleke's Explosive State on the stairwell.

Margaret Roleke's Explosive State on the stairwell.

Or the Ely Center Office, transformed into a gallery for small but mighty things. There is Zohra Rawling’s glinting, stoneware piece Baba Yaga, a sort of fairytale with a hidden underbelly the closer you look. Jade Henderson-Berube’s Alice and I in paper and wood. Dana Scinto’s Cutting Board in ash, walnut, oak and acrylic. A packed hallway installation beckons from the doorway.

Some of the work is literal, still warm and seething in its anger at the current political climate. Up the house’s creaky grand staircase—made bright with Roleke’s Explosive State, painted shotgun shells and wire—a living room long turned gallery comes to life with this elegant rage, its presence bubbling up through the work until it is no longer concealed.

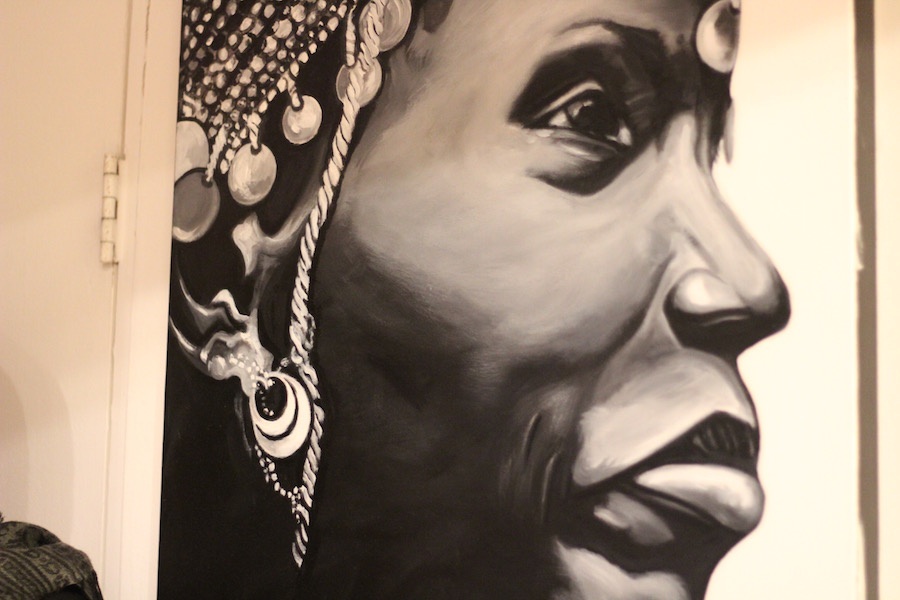

Gabriella Svenningsen’s delicate watercolor of Angela Davis is one in a packed hallway of eye-catching work.

Gabriella Svenningsen’s delicate watercolor of Angela Davis is one in a packed hallway of eye-catching work.

It starts in the lefthand corner of the room, where artists Melanie Carr and Rashmi Talpade have installed large “disbelief pillows” and a set of large, collaged black panels titled Writing on the Wall-Panel 1 & 2 and Writing on the Wall, Panel 2. Pressed up against the wall, the panels spring to life, with a cacophony of blue-and-white printed tweets pasted against solid black background. Around the room, bulbous pillows stand out as a strange sort of point/counterpoint.

Then the anger transitions, and grows—first in an acrylic on panel painting by Matthew Best that just reads Fuck on a deep grey background, geometric shapes hovering at the base. Then to a thickly piled, explosive canvas in blues, oranges, and yellows from artist Dan Makara. In between gobs of paint are pasted headlines: Outcry Growing, Modest Gun Control Measures, Links to Russia.

But it is the painting directly across the room, Rebecca Fuchs’ Nihilominus, that demands the viewer’s eye, and wills them to anger. In it, a visibly pregnant Ivanka Trump stands at the center, eyes out to the viewer, her mouth covered with three red strikes. Around her body, an interlocked web of insults unfolds, all on an orange background. There is every gendered diss imaginable: the victim-blaming She was asking for it anyway to body-shaming Too fat to microaggressions like You want more kids?

Rebecca Fuchs’ Nihilominus.

Rebecca Fuchs’ Nihilominus.

On the floor where Ivanka stands in red high heels, a sea of black-and-white tiles have Trump and Trump-esque statements painted across them. If Ivanka weren’t my daughter, I’d date her, reads one from the side. I think that putting a wife to work if a dangerous thing, reads another.

“It’s about not taking somebody’s shit anymore,” said writer and therapist Karen Ponzio, taking the room in with her husband Joe. (Her poemThey are all delicate now is featured in a first-floor hallway). “Seeing Trump talk to Hillary at debates, saying that—this is what we all go through as women. We’re saying we’ve had enough.”

In hallways and other galleries alike, artists have gone big—like, very big—with that message, and chosen to focus on multimedia installations to make their mark. In the center’s upstairs bathroom, Roleke has taken over, turning a small, humble room into a place where evil dolls come out to fight at midnight. Across the hall, artists Mary Dwyer and Laura Murphy have installed In Grace We Trust, a sort of snapshot celebration of Grace T. Ely’s life and legacy.

It is, ultimately, a hodgepodge that works precisely because it is a hodgepodge: No one opinion prevails, just as no single one is correct or incorrect. On opposite sides of the house, whole conversations unfold around single pieces; Pam Ericsson’s striking, caged Emancipation (collaboration with Richard Davis) and Howard El-Yasin’s Blue Suitcase; Gabriella Svenningsen’s delicate watercolor of Angela Davis and Chen Reichert's handmade Audre Lorde doll; Zohra Rawlng’s fantastical Baba Yaga and Rachel Hamilton’s Good Morning, Sunshine.

The surprise of the show, a second video installation by ECA students upstairs, stops you in your tracks. Kept at the side of a room, it comprises seven computers, all scrolling through the same graphic images in unison. At the center, a white macbook blinks to life. The computers stutter and stop on a message, then begin flashing, bringing up a fast-flying mashup of images from Sesame street to basic computer code. At the center, words appear on the Mac’s screen, as if commanded by an invisible hand.

“Will you speak?” it asks the viewers. The letters delete themselves. “Will you be heard?” “Are you making it worse?” The questions hang heavy in the air.

Back downstairs Thursday, Lovelind Richards was taking a final look at her favorite piece in the show—Leigh Busby’s acrylic on canvas Africa Princess Warrior. An employee with the outreach group Public Allies, she said she is in the process of creating an empowerment program for girls, and wanted to meet artists who were using their work as a vehicle for social engagement. When she’d entered the exhibition, she said she’d had a feeling that she had come to the right place.

“Being a nasty woman is about being strong, being brave—not letting the stereotypes define who I am,” she said. “I am breaking through those stereotypes.”