Culture & Community | Kelley Knight | Storytellers New Haven | Storytelling | Arts & Culture | New Haven

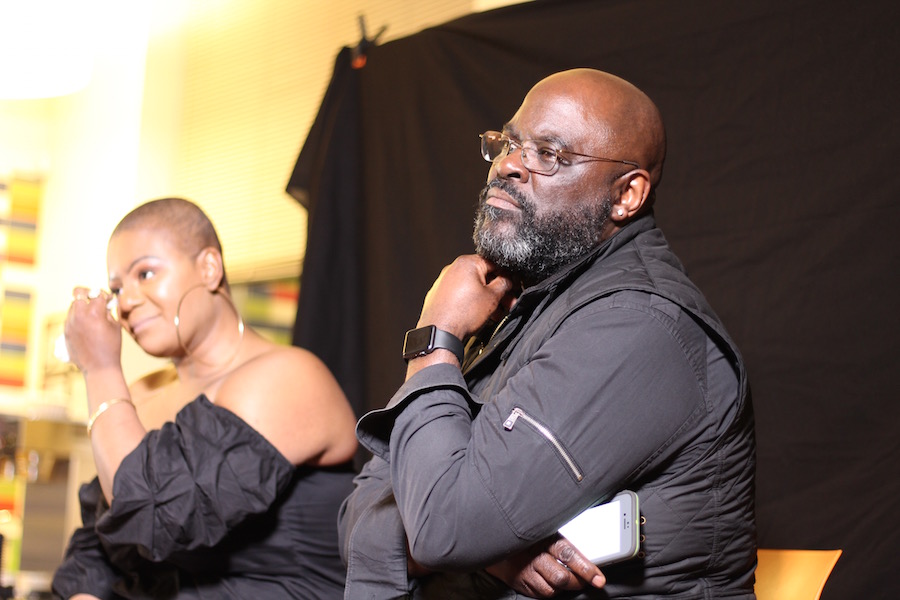

“This is really a true example of what Kevin and I had hoped to build in this storytelling community,” Kevin Walton's wife, Karen DuBois-Walton, had said as the event got underway Monday night. After each story, Walton would return to the front of the room to add questions and moderate for a few minutes. Lucy Gellman Photos.

“This is really a true example of what Kevin and I had hoped to build in this storytelling community,” Kevin Walton's wife, Karen DuBois-Walton, had said as the event got underway Monday night. After each story, Walton would return to the front of the room to add questions and moderate for a few minutes. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Kelley Knight had two tools at the ready if someone entered her bedroom. One was a wooden baseball bat, hidden behind the bed. The other was a wire hanger, out of which she could fashion a sharp point if she needed to.

The night was endless. Every hair on her body stood on edge as she kept herself awake.

Knight brought that harrowing tale to Storytellers New Haven Monday night, as one of two tellers to bring their stories to a packed room at the Connecticut Center for Arts and Technology (ConnCAT). The monthly event, which began in November of last year, is organized by Karen DuBois-Walton and her husband Kevin, and supported by the William Casper Graustein Memorial Fund.

In many ways, the evening’s format has a rhythm to it. One at a time, tellers come from the crowd to the front of the room, and slide into a sort of storytelling hot seat, snuggling into the chair before they look up inevitably at the group, take a breath, and begin. 20 minutes later, there is new knowledge in the room, new history out in the open. Then the group cycles to the second teller of the night.

But in others, it is always an evening of firsts: new voices flowing from the front of the room, unspooling stories of sibling rivalries, tenacious mothers, cross-country travels and unexpected blessings. Monday night, Knight was the first storyteller to not have a connection to either organizer. Instead, she had requested to tell a story last month, after attending the event and staying afterwards to talk to DuBois-Walton and Walton.

“This is really a true example of what Kevin and I had hoped to build in this storytelling community,” said Dubois-Walton. “This really is an open spot for members of the community who want to come and share something.”

A Grandfather’s Lessons And Legacy

Monday’s first storyteller was Rev. OrLando Yarborough III, a geneticist who is also the new pastor of the Black Church at Yale. As he took the seat, he looked out into the audience, to where his wife and young daughter were seated near the back of the room. Then he scrolled to a few notes on his phone.

“What I want to share are stories of my grandfather,” he said. “Things I saw and learned as a young boy that I now try to do as a man.”

He pulled out a gallon-sized ziplock bag with a red zipper at the top, and undid it quickly, history coming alive with the pull of his fingertips, the soft crinkling of the plastic. Out came a small stack of well-worn, shiny photos. A tall, weathered man smiled back from their bright, flat surfaces.

“So you get a sense of who I’m speaking of as I’m talking,” he said.

Two assistants from Baobab Tree Studios handed the photos into the crowd, audience members cradling them as they coasted through the room on a sea of careful hands. As they travelled, Yarborough launched a string of anecdotes, all of them connected.

“My grandfather was a chauffeur,” he said. “I learned from him to be the constant, loving, and steady support that allows others to grow.”

Yarborough time-travelled with the audience, back to the Baltimore County of his childhood. No streetlights. No sidewalks. Trees all around, almost as far as the eye could see. And a big public school that he could take the bus or walk to, where he was always one of the last students to be called, because his last name started with a Y.

His mother wanted more than that for him, he said. So she helped him get into The Park School, an independent private school that was a 45- to 90-minute drive from where he was living. By the fall Yarborough was in the eighth grade, his mother and grandfather had hatched a plan to get him to the school each day.

Each afternoon, Yarborough’s grandfather would pick him up, making the long drive home without any complaint. The mornings were often the same: he alternated with Yarborough’s mother, taking him half the time. So at the end of each school day and as many began, the two would drive through a rapidly transforming Baltimore, watching the city as it changed around them.

“Without his willingness, without his steady hand to drive me and chauffeur me, I wouldn’t have had that opportunity,” he said.

He fast-forwarded with the audience to just a few years ago, as his wife was doing her medical residency in Middletown, Conn. during her pregnancy with their first child. The hours were long, and sometimes unpredictable. And Yarborough began to worry about his wife driving late at night, or growing unbearably tired as residency put demands on her time and energy, and a baby doubled those on her body.

He thought of his grandfather, and shifted his schedule to become her chauffeur.

“I learned from him: whether or not I’m tired, whether or not I have other things to do, whether or not there are other things in my schedule—that’s irrelevant when it’s time to take care of family,” he said. “I practice how to keep high priorities, and not allow them to be sacrificed with lower priorities.”

That legacy of a chauffeur—the grandest, most noble kind, because he was serving family—stuck with Yarborough for another reason too. As his grandfather grew older, Yarborough said he had always imagined driving him around in return for those trips to The Park School. But he’d left Baltimore for graduate school in 2003, and stayed on in New Haven after he was done.

By 2010, Lewy body dementia was taking its cruel course on his grandfather. Maybe Yarborough would never get his chance to be his grandfather’s chauffeur, he feared. He seemed, suddenly, too infirm to leave the hospital.

Then one night in his grandfather’s hospital room, he realized it had just taken on an entirely different meaning. His grandfather had instructed Yarborough to get his hat, and then his shoes.

"Where are you going?" asked Yarborough.

“I’m going home!” he answered.

He wasn’t going home. He was too sick by then. “But I put him in that wheelchair and I just pushed him around the hallways,” Yarborough said, his voice wavering as the memory bloomed out before the audience. “And that was the one time I got to be his chauffeur.”

That was only lesson one, he cautioned the audience. Lesson two: Honor and value everyone.

Like the time young Yarborough watched, just a boy, as his grandfather attended to a parishioner at their church who had urinated on himself. The family had been at church, and Yarborough’s grandfather methodically helped the man wash up, dress using some of his own clothes, apply a bit of perfume, and air out outside.

Yarborough put that memory to use during a recent trip to Church On The Rock New Haven, as he and his wife were teaching a class in financial literacy. As Yarborough spoke to a man at the front desk, he noticed “drops of poop” coming through the man’s pants, and falling onto the floor.

“I was trying to think, ‘How can I not embarrass him? How can I not draw attention?’” he recalled. “That was one of my steps to honor people for who they are, and not try to disgrace them or embarrass them with something different.”

He wiped the poop up with a paper towel, then covered it so no one would see.

“What I learned from my grandfather that day is make people look better than they are,” he added.

His grandfather had also passed down a remarkable trait, Yarborough continued—an utter suspension of judgement, from the guy that had read his electrical meters to his medical staff, to his parishioners and religious family. That extended to those who took over Christian school and church programs that his grandfather had created, expanded, and secured during his time in the church.

“He developed leaders who developed other leaders,” he said. “He wasn’t the type of person who would take all the responsibility all to himself without allowing other people to share into that responsibility and be developed.”

It’s something that Yarborough is working on in his own ministry, he told attendees. That “I have to be willing to take my eyes off myself and my eyes onto them.”

The stories kept coming. His grandfather was a gentle “builder of self-esteem,” never comparing his own struggles to those happening around him. He was sacrificial and humble, learning how to read and write with Yarborough’s mother, as practice for adults that she was tutoring. He was “a trailblazer,” navigating his own path through marriage and fatherhood when he didn’t have a paternal role model.

He refused to gossip when other members of the church did. He was trusting, listening to his family members as they whispered away his dementia-induced hallucinations. He was a good neighbor “to someone who couldn’t pay him back,” helping an elderly woman clear her possessions with a dumpster and trash crew. He was fit, walking five miles a day until he was at death’s doorstep.

“He was a teacher without words,” he said. “I was able to read the book of his life without him talking a lot about it. Even though he was a man of faith, and even though I follow in hi footsteps, we never really talked about the Bible … he just lived it before me in a way that I could catch it.”

Yarborough’s grandfather died in spring 2017, almost exactly a year ago. Now, the pastor said he is trying to preserve his memory by living his life in the same way, from walking each day on the treadmill to brainstorming how to get his Black Church at Yale students more involved in their religious lives.

Now, he said he’s looking to a final memory of his grandfather for support. At his grandfather’s funeral, there was a bus ferrying his grandchildren to where they needed to be. The chauffeur of the bus was a pastor from a nearby church, which his grandfather had attended for almost three decades. The pastor, Yarborough recalled, “didn’t think it was beneath him” to be driving a bus, taking family members from one point of reference to another. No. He thought it was the honorable thing to do.

“That’s the type of relationship I want to keep,” Yarborough said. “When I get older and I’m unable to do things and I need help, there are still some people that—they recognize that they knew me back when. That I didn’t just honor them, but I loved them in a way where they can continue to love me.”

“And I Grow Everyday”

As Yarborough headed back to his seat, lifelong New Havener, actor and playwright Knight rose to take his place, joking that she was too short for the chair as she wriggled into it. A smattering of laughter came from the audience. Then she got serious.

“I am here to tell you how I almost did not make it here today,” she began. “How for quite some time now, I have been almost always just a few moments short of not quite making it.”

If Yarborough spoke in linear, gradual steps, Knight was taking the VHS out of its player, undoing its shiny, black reels of film, and assembling it all slowly again, each step slow and careful. Bouncing between her typed story and the audience, she opened not with a forward marching narrative but with a binding wave of feelings, each rising over her head until it seemed like she might drown.

“I have stopped seeing the sun,” she said. “No. This won’t be a build-up of romantic figurative and symbolism. I have literally gone months without seeing the sun. It is there but it does not shine on me. I have lost track of day and night. I am always, always exhausted—but I am restless and nocturnal in the night and narcoleptic in the day.”

Knight described deserted land where anxiety, depression, panic attacks live, coexisting on bathroom floors with tile grout, in bedrooms with the fear of what may come with nightfall. She brought the attendees into her home and her head, reviewing the process she has used to pull herself through each night.

Were the windows locked? What about the back and front doors? Had the stove been turned off? Had anyone double-checked that the stove had been turned off? The two baby gates, the flimsy one and the strong one? Were there weapons at hand in the bedroom?

The threat of invasion was everywhere in the room now. She took a heaving breath, something catching in her throat. The audience sat on edge.

“When I stumbled upon him those many years ago, there was nothing dashing, charming, or smooth about him at all,” she continued. “Every edge was tattered and torn. Every feather was ruffled and out of place. He was broken … and so I mislabeled every red flag as a fixable flaw, and made it my god-given mission to love him unconditionally. To fix him. Because if I could fix him, I thought we would be perfect together.”

A few attendees had already started crying; now a few more began, as Knight’s abstracted terrors gave way to a physical form. She took the audience through the beginning of their relationship—a “broken bird” released from prison, who became the father of her twin girls in November 2012, and struggled with depression.

The following year, as she was caring for two 1-year-old girls, she got news that he had overdosed, seizing on the floor of a restaurant before being sedated by medical crews who had arrived. That wasn’t what had scared her most about the ordeal, she told the audience.

Knight after the performance, with friends who came from as close as New Haven and as far as New York.

Knight after the performance, with friends who came from as close as New Haven and as far as New York.

“When he came to he was smiling,” she recalled. “Not because he was grateful that his life had been spared and that he was able to come home to his children. No. He was filled with pride because he had cheated death. He was invincible now. And this high was greater than any high he would ever experience.”

What followed in the next months, Knight told the audience, was the most terrifying week of her life. It began with an argument, and a final message from him that he was leaving for good.

“Just like that,” she said. “Without a moment of hesitation, he was gone.”

But he wasn’t gone, she would learn slowly. First, her sister’s car was broken into, her credit and debit cards stolen, used, and then put back in the car with a note that read “I know what school you go to.”

Then a cement boulder flew through Knight’s second-floor bedroom window, making it across the room before falling to the floor with a thud.

Then threatening social media messages, threatening to burn her house down with the family inside. “You’ve got five days before I burn your house down,” one read. “The last time I was over there, I heard kids.”

The sound of Knight’s sobbing filled the room. On one aisle, attendee Ife Michelle Gardin tiptoed up to the front, offering Knight a tissue that she held tightly in her fist, wiping the tears as they fell from her face. Knight continued the story, choking out words. The harasser, she said, continued to threaten her.

Until her mother was going out of town, and she called her children’s father, telling him everything, “down to the smallest detail” of a harasser that remained anonymous to her. He offered to stay at Knight’s home, sleeping at the bottom of her bed until her mother returned.

It was only after he left—and her mother and sister pointed out that nothing had happened during that time—that Knight put pieces together, as they “uncovered for me what my mind would not allow me to comprehend.” That the attacker, the harasser, he ex-boyfriend were all the same person.

“I had no idea how much of a sociopath you have to be to secretly terrorize the woman that loves you and pretend to be something that you are not in order to afford yourself the opportunity to watch your victims sleep,” she said.

She was deep in the depths of depression, she said. “But I had to live for my daughters.”

Since, Knight told the audience that she has been doing just that, moving through both depression and the hope for another, kind father figure for her daughters day by day. She recounted a mantra that she repeats each say with her daughters, “two of the most amazing people that I have met in my whole entire life.”

I am big. I am great. I am magical, I am brave, I am strong, I am beautiful, I am smart, I am kind, and I grow every day. And I grow everyday. And I grow everyday. And I’m cute.

Laughs and applause filled the room. Not long after it had subsided, a hand went up from the back. Stetson Library Branch Manager Diane Brown’s voice, soothing and even like a salve, travelled to the front of the room.

“You’re not alone,” she said.