_2017.jpg)

Culture & Community | Kyle Kearson | Arts at Work | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts

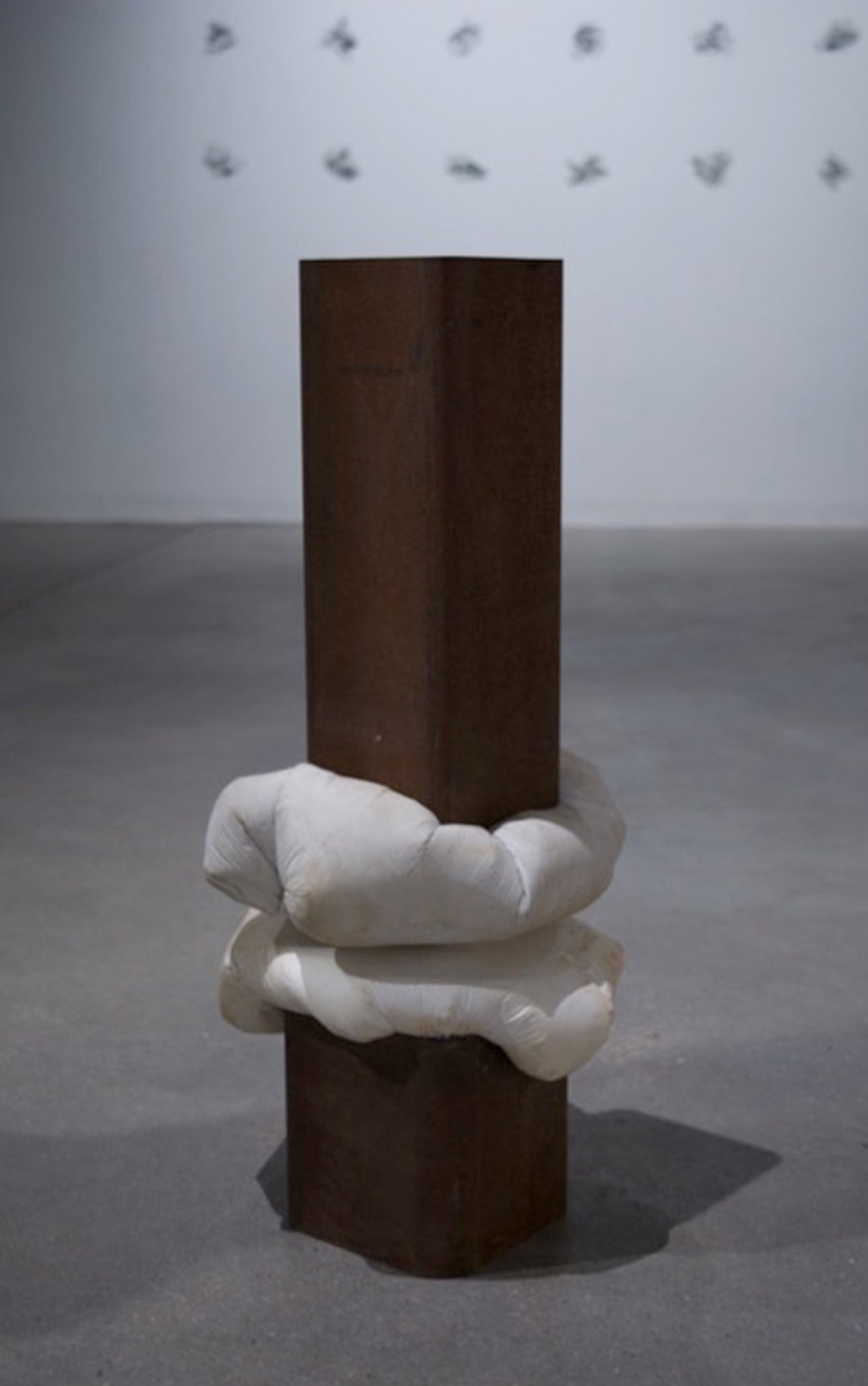

New Sphinx , 2016. All photos courtesy Kyle Kearson.

New Sphinx , 2016. All photos courtesy Kyle Kearson.

What do you do?

This is usually the first question I’m asked in new situations, when people want to know about my profession. The short answer is community outreach at Long Wharf Theatre, where I act as the Community Engagement Manager. But the long answer—and it’s much, much longer—often gives me pause.

As an artist, arts administrator, producer, director, and organizer, it’s hard to distill that identity into a job description. No two days are the same on the job. And I hypothesize that’s the same for many in the field.

As someone who is constantly asking “Why do this? Why choose the arts?,” I wanted to dig a little deeper. This is the second installment in a series of interviews on the arts—fine, performing, culinary, and more—and their practitioners at work in New Haven.

Work is one of the central tenets of culture in America. This is an opportunity to get a look into the worlds of the people that make art happen in this city.

In the first installment, I spoke with cellist Ravenna Michalsen. If you haven’t read that, go check it out. What follows is an edited version of the conversation I had with sculptor Kyle Kearson in his studio in Erector Square earlier this year.

* * *

What do you do?

I am sculptor and an art handler.

What does that mean?

I work as a museum technician at the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA). I help with installation, setting up the exhibits, maintaining the space, transporting the art work. I’m in the museum from 8am to 4pm Monday through Friday. That’s my day job.

I’m also a practicing artist. I’m trained. I got my BFA in sculpture and ceramics. After work, I continue to try to make sculptural works that excite me and keep my thoughts going.

What is a day at the museum like?

A regular day can be described in two seasons. When we’re in the midst of setting up or breaking down a new exhibition, it’s hectic. Every step of the process. Whether it’s receiving all the crates full of art work, late night deliveries, taking inventory of the work that’s going to go up. That’s all physical labor, exhausting work, a real investment with my body.

Along with that process comes hanging the show, opening everything up, hanging paintings on the wall, mounting sculpture, installing all the precious objects that are going to be seen in the next couple weeks. So it’s busy busy busy, go go go, all day.

The second season is more a quiet time, when the show is up and running, there’s not as much to do. We’re doing the maintenance. We’re dusting, we’re transporting here and there. If a painting needs to go to photography, or get brought out for somebody that’s doing a study. Or if a curator wants to do a change on the floor. It’s a little bit more low key. But the same process, just less hectic.

Black Power Connection , 2016.

Black Power Connection , 2016.

What is the training like for art handling? How did you wind up doing that work?

I really learned on the job. I started there as a New Haven Promise intern. I went through the Promise program in college, they provided a scholarship and had the opportunity for internships at many different organizations and jobs around New Haven. I ended up at the YCBA. I got to come on the summer of 2016 and really developed a good rapport with the team. I got asked to stay on for the next show, and that turned into being picked up full time.

That’s amazing.

It is amazing. It’s truly a blessing because some of the people that graduated with me from art school are still looking for a job that can meet their needs.

How does it relate to your studio time—as both a sculptor and an art handler? What does the transition look like between those things?

Sometimes it’s a symbiotic relationship. Sometimes I leave my job very excited about going to make art because I’m surrounded by art every day. Often I’ll be inspired—even by the building I work in. It kinda like peaks my mind in terms of materials. It’s a famous Louis Kahn building and there’s a lot of concrete. Do you ever come by to visit?

Oh yeah. Especially in the winter. I like going on walks to clear my head. Especially when it’s cold and gross outside, it’s still beautiful in the art gallery.

Yeah that’s true. You talking about the YCBA? Not [the Yale University Art Gallery] across the street?

I go there too. I really like the YCBA. I’ll go up to the Turner room and find it very peaceful.

You are truly an art-y person.

Is there a rivalry?

There’s a rivalry! Because they do them, we do us. We’re separate. I’m glad you’re familiar with the building. To be in there and look at our collection, it’s beautiful and inspiring.

Sometimes I’m excited. Sometimes if we’re in that busy season I’m tired and I can’t make it over here. I gotta weigh what’s most important. What’s most important is my wellbeing. I try to come here as much as I can. I love it. I come here sometimes just to break free. A lot of my stuff that is labor intensive is a workout and a release.

Like if I’m mixing up cement or if I’m breaking a panel down, there’s a release of built up frustration or just enjoyment in the studio. I’m in the lab experimenting.

How did you wind up working in sculpture?

That’s a funny story. I went to college with the goal of becoming a mechanical engineer. I liked it. I thought I knew what it was. It was tied to my childhood dream of becoming an architect, but they aren’t the same. My college didn’t offer architecture, I thought I’ll do this, it’ll be a good job, a fruitful career and I’ll have some sort of creative practice. Freshman year I realized that wasn’t going to happen, it wasn’t for me and that there wasn’t enough creative freedom in that area of study. I made my way to the art school.

I was still treading lightly—thinking I’d do graphic design, because of the same mentality, get a job, security, money. I ended up taking a clay class, hands in the mud my heart was just opened up to the world of sculpture.

I’ve always loved art ever since I was young, but I never considered it a true career until studying it at UConn.

+Detail+1.jpg) Detail from A Reflection (Red).

Detail from A Reflection (Red).

When you loved as art as a kid, you wanted to be an architect?

Yeah, because I love the creative aspect of it, but then the tangible architecture. These buildings are the biggest sculptures you can experience. They’re a work of art and they serve a vital function.

And going to work in the building that you do, you’re surrounded.

Do you have favorite pieces in the gallery?

It’s hard to say. I do. I like most of our contemporary work actually. There’s one piece that we don’t show often. But it was out when I first visited. Rachel Whiteread. She makes these amazing casts out of the negative spaces of furniture and other architectural pieces—like doors and I think she did a whole house one time.

She had cast the negative space of this conference table. It was these huge white blocks. It read well. It was different than everything else I saw around.

There’s a lot of traditional work around. But yours isn’t. Do you find yourself working in opposition of or inspired by work from the day job to the studio time?

Kind of, yeah. British culture is undeniably tied to colonialism and some of that shows up at my job. Even just living with some of the works that depict times of slavery or invasion of certain lands, it can be upsetting. I guess I do come here and rebel in some ways. But, if I didn’t work there I’d still be doing some of the same work because i’m dealing with issues I see in society.

I think our collection is wonderful for its vast nature and there’s no denying the great artists that have made great work.

There is an entrenchment in that colonial environment—so the idea of greatness has pros and cons.

For sure. We could talk about the works that we value and deem as great as being written by the people who are making the history, so who is claimed in the canon is of a certain demographic.

_2017.jpg) Land of the Free (Disintegrating), 2017.

Land of the Free (Disintegrating), 2017.

You’ve talked about liberation as a theme in your work, can you tell me a little bit more about that?

I identify as a Black sculptor. I’m an artist of color. I’m of a biracial background. My father is Black, my mother is white. Growing up I had to process that and grow into myself and figure out who I was. I’m still doing that today. My work is through my lens looking at society and a lot of the implications of the outside world on certain people.

I’m looking at established structures and systems in place that hold people back, or were meant to hold people back, limit people’s freedoms. I’m trying to make work that makes people think about that stuff, think about the histories and what’s still present today.

For me it comes out through tactility. The material carries so much emotion. I use concrete a lot. It’s a real heaviness. While that’s not directly racial, or loaded with any ethnic connotation, the industrial nature of it speaks to my urban environment, and just the making. I’m a real maker, and I think Black folk have always had to make a way, make their own way.

What are you working on right now?

Right now I’m working on a few projects. This cast is part of a sculpture called “A Dream Deferred.” A concrete block is going to rest on top of a beautiful cloudscape built from fabric, in a big billowing form. This weight is literally going to rest on it, the title, the Langston Hughes poem, is talking about how the exterior forces will try to limit you by saying wait or don’t as a way to stop you reaching towards the sky.

Some poetic stuff, some more overt stuff, some conceptual stuff. There are these freedom bricks I’m developing, another piece in process called “Land of the Free.” My goal is to lay out this floor form of nearly 300-400 white bricks. Each has the word freedom falling into it. I was thinking about where we are today, there are many freedoms that are disintegrating. Our country was supposedly founded on these freedoms for all people but that’s obviously not the case. This installation would be this walkway of whiteness that is presenting who the freedoms were for.

There’s an internal contradiction about the labor, and who would actually put down the infrastructure and early foundations. The enslaved people that worked for our freedoms.

Compression , 2016.

Compression , 2016.

If somebody wants to go see your work, where can they go?

Right now you can find out more directly from my website. I participate in City-Wide Open Studios and am always trying to make connections and show around town.

Where do you hope this takes you? What do you hope either the day job, studio time? What does the journey look like do you think?

I’ve been questioning that a lot lately, because I want to be free to make my work full time. By 50, I hope to be in a professor position. Well established, continued my practice and develop a name for myself internationally and then be able to influence the minds of college aged students.

It was in my undergrad training that I really began to take this art stuff seriously and the impact that it could have I want to work with young people and motivate them to use their voice to say something. Use their hands to make something. Use their art to do something.

Why New Haven?

I’m born and raised in New Haven. I’ve been here and I’ve never gotten tired of it. This scene is really poppin’. It’s really bubbling with so many creatives, so many opportunities to connect and network with people that are doing amazing projects.

I love New Haven for its highs and its lows. There’s literally a very full experience of the human spectrum here. We have Yale University and we have neighborhoods of richness with so much culture to experience.

I don’t want to just compare Yale and neighborhoods. They are just two facets. And they intertwine. There are some walls, but there are some bridges and tunnels too.

For sure. I think you’re right though about walls too. That’s something i’ve noticed after beginning to work at Yale, how much it has a relationship or doesn’t with neighborhoods.

Actually at the YCBA, they have some connection with New Haven Public Schools that every student will visit the museum at least twice between K-8. I visited it when I was little, and now I work there. There’s this whole cycle of growth.

So much to explore. So much to learn.

Anything else you want to add?

I just want to add, that New Haven is poppin’. I know I said it. But it’s poppin’.