Suzan Lori-Parks | Arts & Culture | Theater | Tracey Massey

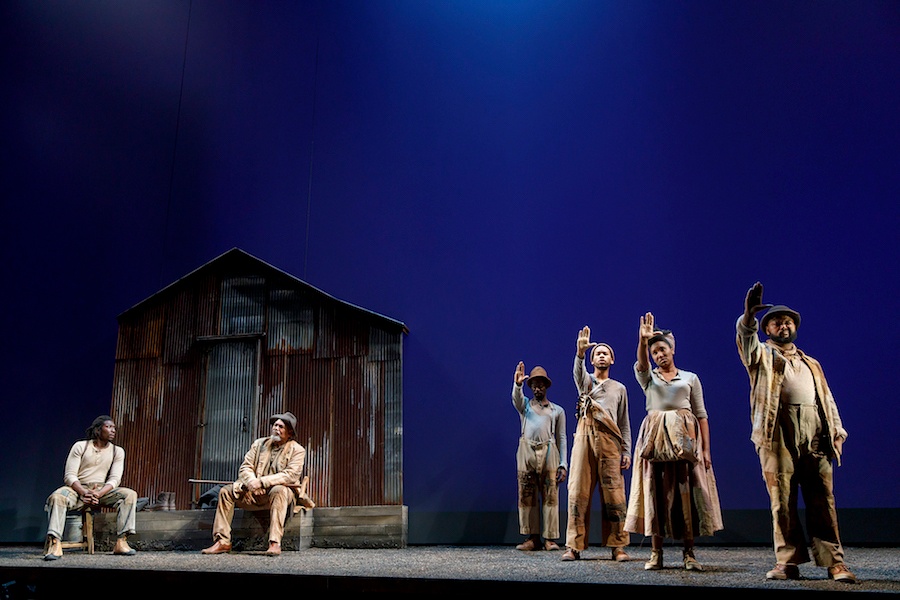

Members of the company of Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

Members of the company of Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

On the University Theatre’s low-lit stage, Penny was puzzling over a large, egg-blue scrawl of her name, trying to figure out what a scribble in the sand might mean.

In the second seat of the second row, Tracey Massey was watching her every move and thinking of her mother, who had never learned to read.

Massey is a student at The New Haven Adult & Continuing Education Center, where she is enrolled in a high school credit program. Penny (Eboni Flowers) is a character in Suzan-Lori Parks’ Father Comes Home From The Wars Parts 1, 2, & 3, on at the Yale Repertory Theatre through Saturday night.

Thursday morning, their worlds collided at the Rep, as Massey filed into the theater with her civics and history teacher and classmates, and took a seat close to the front of the house.

The trip came as part of the Rep’s WILL POWER! program, for which New Haven area students attend a matinee performance and talkback during the final weeks of a show. This marked the season’s second and final program; the first took place in December, in conjunction with Nambi E. Kelley’s adaptation of Native Son.

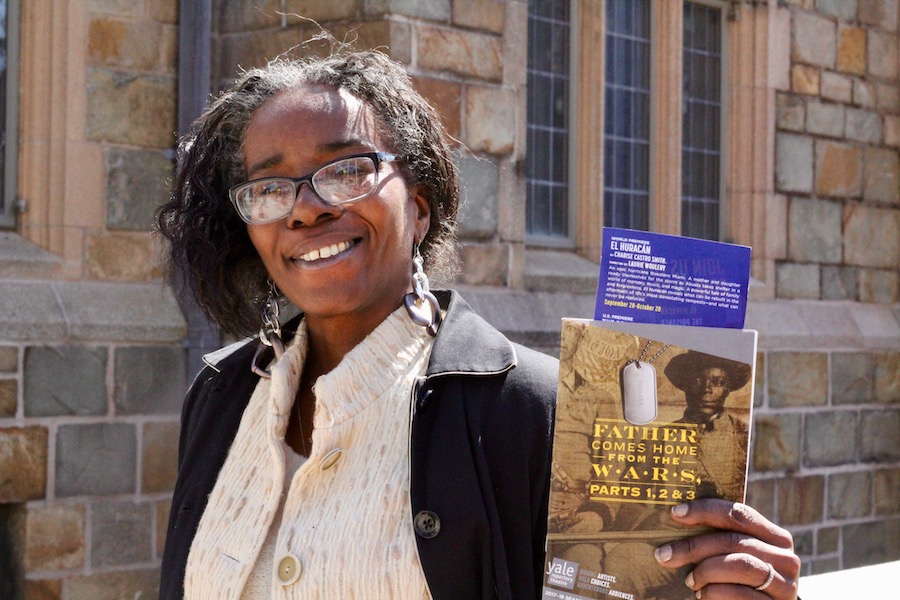

Tracey Massey: “It brought back a lot of memories of just seeing the state of mind that my family was in and not understanding why we were so different. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Tracey Massey: “It brought back a lot of memories of just seeing the state of mind that my family was in and not understanding why we were so different. Lucy Gellman Photo.

Directed by Liz Diamond, Father Comes Home From The Wars opens on a world within worlds, as a chorus of captive slaves (Chivas Michael, Safiya Fredericks, Erron Crawford, Rotimi Agbabiaka,) triangulates under a starless blue night and angles its hands toward the creeping dawn. They are at once in two places: bare, sprawling West Texas, where the first part of the the play takes place, and on stormy seas, as the slave Hero—or is it Odysseus?—embarks on a great and complicated journey for a great reward, and will struggle to make it all the way home.

At least, it seems like that’s where they are at first. The set is minimal: a rusted shack, and enough empty space to imagine tumbleweed and field reaching out to the horizon line. It could be 1862, in which part one is set. But then again, it could be a century later, just a hair short of the historic March on Washington and Aretha Franklin’s “ain’t nobody gonna turn me around,” referenced in part three of the play.

Or several centuries earlier, as the Atlantic slave trade began pulling bodies from their rightful home, separating a history from its birthright.

For Massey, it was the South Carolina of her mother’s childhood. Pulled out of school in the fifth grade, her mother and aunts never learned to read, spending their schooldays picking cotton on a sharecropping farm. Then she grew up, married a Korean War veteran, and began building and raising a family of 10 children. During her own childhood, Massey would return home from school, get out the family bible, and read to her.

“I can relate to this story,” she said, eyes still focused on the stage, where actors were milling around after the show. “My mother dropped out of school in the fifth grade … her parents died when she was fairly young. The sisters took care of each other by working the fields.”

Chivas Michael, Eboni Flowers, Safiya Fredericks, and Rotimi Agbabiaka in Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

Chivas Michael, Eboni Flowers, Safiya Fredericks, and Rotimi Agbabiaka in Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

As Massey watched, thinking of her own family, she found a play that is not without humor and sweeping feeling. In painting her characters, Lori-Parks has woven a deeply human and humanizing world, that includes laughter and twangy, sweet anecdotes that bring us in and keep us there.

There’s a great love between Hero and Penny, as he lifts her like a Greco-Roman statue and she proclaims that she is flying, expanding her wingspan just so. Or a gregarious and slobbering dog (Gregory Wallace), who is so wholly unexpected he bends the script with each breath—and at least one howl. Meanwhile The Colonel (Dan Hiatt), who we hear about in the first part and see in the second, is a buffoon, made wicked by his whiteness. He is the slimy butt of a slimy joke, the punch line of which we can laugh at for a little while.

Yet when he proclaims “I am grateful each day that god made me white;” when he recreates a slave auction and estimates Hero’s price with a Yankee soldier (Tom Pecinka); when the dog’s absurdity gives way to the violence we inflict on one another, there is a degree of timeliness that settles in your gut as a cold, hard knot, writhing and swelling into something ugly.

Something in that bubbled over for Massey, a sales rep for Mary Kay, mom and grandmother who is working towards her diploma.

James Udom and Tom Pecinka in Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

James Udom and Tom Pecinka in Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

“It brought back a lot of memories of just seeing the state of mind that my family was in and not understanding why we were so different,” she said after the play. “Why we had to live our life sharecropping, not being well educated. Not having the rights that other cultures have. And to see the struggle of my family for so many years, and still to this day.”

That crushing weight of history, signature to Lori-Parks’ work, is doled out in meticulous and sometimes tablespoon-sized references in the play. Characters are rooted in their heavy 19th century existence, but also in Kara Walker’s Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders of those who have come before and those who will come after, in the Black Lives Matter Movement. This, they say without ever having to say it, is a great and blistering continuum with no end in sight.

As actors trickled onto the stage for a short post-show talkback, Massey’s hand was one of the first to go up. In the through line of her arm to her fingers flowed her own history of migration: New Haven to South Carolina and back, jumping around neighborhoods from Newhallville to Dixwell to the Hill to Fair Haven, to the classes in history she’s taking to finish her degree.

With a portable mic in hand, she honed in on a scene where the audience learns that Hero sliced Homer’s foot off with an ax, as the "boss master" (Hiatt) held a gun to his head. And another, where Hero recalls falling in lockstep with The Colonel, even while fighting for the South during the Civil War.

“How did you go about seeing yourself in your master?,” she began, watching Udom intently. “How can you explain that to us?”

Udom paused. “I have my own justifications for it,” he said. “Myself as the actor versus Hero—I have two complete different viewpoints. There’s certain things that I feel like myself I wouldn’t do, but Hero does do because of the circumstance he’s in.”

James Udom in Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

James Udom in Father Comes Home From the Wars, Parts 1, 2 & 3 by Suzan-Lori Parks, directed by Liz Diamond. Photo by Joan Marcus, 2018.

“In terms of the actions that he takes in that last speech [later in the play] … I think that it’s an element of PTSD and sort of Stockholm syndrome,” he added. “Where your oppressor—when that becomes the norm for you, it’s reflected in the behaviors you take on yourself.”

“I think it’s still true today,” he added. “You take on sort of those things they put on you, and start to behave in some type of way that you may not recognize.”

“I just think it’s important to recognize and understand that the people represented in this play are living through multiple layers of trauma,” added actor actor Chivas Michael. “Multiple layers. When George Zimmerman got off from shooting Trayvon Martin, I had a genetic memory, a deep, deep sense, of lack of safety.”

“It wasn’t something that I knew. But it was something that my body literally bristled. It was like: Oh my god, we’re not safe. And I just knew it. It was a feeling that I had. And I think that those multiple layers of trauma live in this country, period. But especially for these people who we’re representing onstage.”

For Massey, that question was the tip of the iceberg. Watching the play, she said her mind had flashed back to her childhood in New Haven, where she was raised as the “knee child” or second youngest of five girls and five boys. When she was 12 years old, her parents separated, and her mother took all 10 kids to the South. Her entire family was there, Massey said. It was 1985, and she was the only one of 10 children who didn’t like it.

“It was the biggest culture shock I ever had,” she recalled. “For her [my mother], it was coming home.”

In its sticky heat, South Carolina marked the beginning of Massey’s own homecoming. After a childhood split between New Jersey, Connecticut, and South Carolina, she made her way back to the East Coast, ultimately welcoming children and grandchildren into her world. Her sibs, she said, have remained mostly in South Carolina with family, and so a mental part of her lives there too. It always will. When she saw Flowers onstage, that catapulted to the front of her mind.

“That touched me,” she said. “There are people that can’t even recognize their own name.”

As the talkback wound down, Massey approached Udom, who knelt down at the corner of the stage to hear what she had to say. In quiet tones, Massey let her story pour from her, thanking Udom for bringing it so vividly to life.

“Hero, you’re my hero,” she said.

An usher reminded Massey that the actors needed to start an understudy rehearsal, and then insisted she leave the theater before finishing her thought. Udom opened his arms for a hug, drew her in, and then whispered something in her ear.

She didn’t know what he uttered, she said later. But it left her wanting to return to the theater, many times over, that she might travel back somewhere else.

Father Comes Home From The Wars Parts 1, 2, & 3 runs through Saturday, April 7 at the Yale Repertory Theatre, 222 York St., New Haven. For tickets and more information, click here.