Culture & Community | LGBTQ | Politics | Arts & Culture | New Haven | New Haven Pride Center

.jpg) Ash Cruz, who is a published poet, works through what he would depict if he'd been at Stonewall in 1969. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Ash Cruz, who is a published poet, works through what he would depict if he'd been at Stonewall in 1969. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Ash M. Cruz was midway through a sign commemorating the Stonewall Riots when he realized that he needed another color for something punchy. The words STOP HATE/START LOVE arced around the sidesof his poster in red. He reached for two new bottles of paint. A blue and yellow flower began to bloom at the center.

A high schooler in New Haven, Cruz didn’t live through the Stonewall Riots 49 years ago. He didn’t spend time at the historic bar last weekend, as New York Pride spread its complicated rainbow across the city. But he’s learning about that history—and his—as a camper in “The Children of Marsha P. Johnson,” a free, weeklong summer camp for queer youth of color organized by “artivist” Juancarlos Soto and 18-year-old Jeremy Cajigas.

The program is supported by Planned Parenthood of Southern New England (PPSNE), Citywide Youth Coalition, and the New Haven Pride Center (NHPC), where it is housed through June 29 among a current exhibition of artist Ricky Mestre’s work.

The title of the camp commemorates the seminal Black transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson, one of the first to stand up to law enforcement in the Stonewall Riots of June 1969 and a lifelong advocate of LGBTQ+ rights. Informally, Soto has also given it another name: “Black and Brown Queer Camp.”

The idea for the program was born last fall, when Cajigas joined Soto as his intern at PPSNE. A longtime member of Citywide Youth Coalition and co-founder of the student activism group Fighters for Justice, Cajigas struck Soto as a natural organizer, particularly nimble as they worked with community members who identified as queer and Latinx. So when they suggested a weeklong intensive for geared toward queer Black and Latino youth, Soto jumped at the idea.

It was new, but familiar, territory. Last summer, Soto led a weeklong “leadership boot camp with Latinx folks” at Bregamos Community Theater in Erector Square, sending a new cohort of Latinx activists and organizers back into the city when it was over. Last April, Cajigas piloted a three-day program called “Black Gay Pride,” geared toward educating community members about the murder of Black trans women. So when Cajigas insisted on making the summer program a week long, Soto agreed. The Pride Center offered to host the group for free.

Jeremy Cajigas and Jaylla Brantley. "What would your poster have said if you were at Stonewall?" Cajigas had asked the group.

Jeremy Cajigas and Jaylla Brantley. "What would your poster have said if you were at Stonewall?" Cajigas had asked the group.

“It’s always been about creating spaces that I wanted as a child,” Soto said, noting his previous work organizing youth at JUNTA for Progressive Action in Fair Haven. “This was really the intent for this … to have more spaces. We really hope that we can continue to do this every year, and every year gets bigger and bigger.”

During the week, Soto added that it’s important to him to see the campers grow as facilitators and organizers, so that they can bring the work they are doing back into their communities. While most participants are from the greater New Haven area, at least one camper has been commuting in from New York City, because there isn’t something similar where they live. So far, he said the end of each day has been a “proud papa moment.”

It is for Cajigas too. Dipping into the center’s small lobby on a break, the newly-minted graduate of Riverside Education Academy recalled watching groups like LGBTQ+ Youth Kickback dissolve, and not knowing where to turn to for queer activism, advice and peer-led support. They recalled coming out to Puerto Rican, Pentecostal parents two years ago, and not being sure that there was a safety net to fall back on if their parents asked them to leave the house (“I had bags packed. I had a friend waiting outside.”) They said they were tired of using YouTube videos as their biggest LGBTQ+ frame of reference.

Jeremy Cajigas with Mia Joseph.

Jeremy Cajigas with Mia Joseph.

“I was teaching self-love [in my activism], but I wasn’t doing that for myself,” they said of the years that fear kept them in the closet. “Even though I had a support system outside of home as far as friends, I didn’t have queer friends that I could talk to about it, or ask them about their personal experiences. So a lot of my role models were on YouTube.”

Since coming out, they added, they’ve taken a “deeper dive into my sexuality with my parents.” But that “for me, creating this space is really creating a space I wish I had when I was younger The safe space I always wanted, and never really had.”

Cajigas added that they would like to see The Children of Marsha P. Johnson grow into a multi-week summer program, but that none of the group’s participating partners have the resources to do so right now.

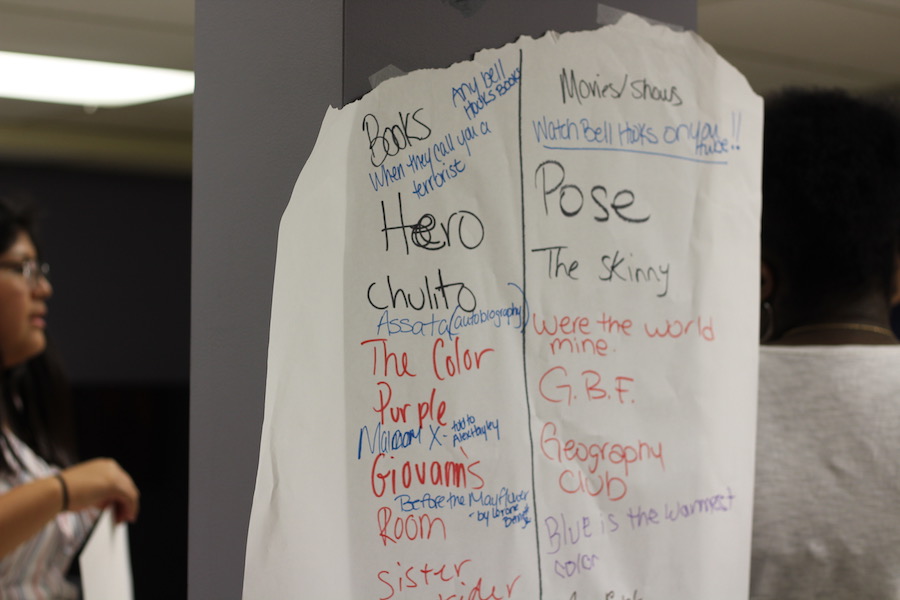

Back in the NHPC’s brightly lit main room, campers pulled out glitter glue, tubes of bright paint, colored pencils, markers and thick-tipped paintbrushes to decorate posters they would have carried to the Stonewall Riots had they been alive in 1969 (almost all of them are high school students or recent high school graduates). A growing list of LGBTQ+ book and movie suggestions including The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson winked out from the wall.

Just moments before, Cajigas had spoken briefly about the riots, reminding campers that trans women of color—Johnson and Sylvia Rivera among many others—didn’t just participate in Stonewall, but led them.

Around the room, campers took to their blank posterboards with a combination of words and symbols. Working over a series of tables, they spread out, decorating them with the slogans like “We’re Here/We’re Queer” and “Respect Our Rights!” in rainbow and monochrome lettering. The soundtrack from the FX series “Pose” pumped through the room with seething bass beats.

“For me, this just means that there’s a safe space that people can go to,” said 17-year-old Mia Joseph, a rising senior at Metropolitan Business Academy. “It is a resource for people who might otherwise not feel safe, in otherwise other dangerous areas. That’s real. You don’t get a lot of spaces like this in New Haven, never mind the greater New Haven area.”

Mia Joseph: “It is a resource for people who might otherwise not feel safe, in otherwise other dangerous areas. That’s real. You don’t get a lot of spaces like this in New Haven, never mind the greater New Haven area.”

Mia Joseph: “It is a resource for people who might otherwise not feel safe, in otherwise other dangerous areas. That’s real. You don’t get a lot of spaces like this in New Haven, never mind the greater New Haven area.”

“The fact that this entire building is even available to us is, I think, a step in the right direction,” she added. “I want to see more spaces like this pop up. I want more youth to know about this, and I want more education about LGBTQ+ issues for everybody.”

Earlier in the day, camp staff had worked to fulfill that educational mission with a reshaping of 20th century queer narratives from facilitator Ty Cooper. A Virginia transplant, Cooper said they are still getting accustomed to Connecticut—but that working with campers to restore queer histories to their rightful owners is helping that adjustment.

“A lot of our history has been erased by colonization, because we’re seen as less than,” said Cooper. “It was very difficult to pull some of our histories out from before the 1900s. So I know we existed, because queerness lives in spite of everything. We’ve been here since the beginning of time.”

After recommending Omise'eke Natasha Tinsley’s “Black Atlantic, Queer Atlantic: Queer Imaginings of the Middle Passage” (get the full text of here), Cooper jumped ahead to the Harlem Renaissance, “full of Black queer folks who was out here living.”

Ty Cooper: "We’ve been here since the beginning of time.”

Ty Cooper: "We’ve been here since the beginning of time.”

These figures, they said, were the history-makers and creatives that laid the groundwork for what would come later in the talk: the Mattachine Society in the 1950s, Bayard Rustin’s work as a founder of the Civil Rights movement and 1963 March on Washington, and the need to talk about “Black queer folks holding up Black cis men.”

The timeline flashed on. There were Stonewall Riots at the end of the 1960s, and learning “how we got to where we are now.” Or the 70s, with LGBTQ+ activist and Shoshone elder Clyde Hall’s reclamation of the “Two Spirit Movement” in the Native community. Cooper invoked the poet Chrystos, and then moved swiftly to the 80s and 90s at the height of the HIV and AIDS crisis, where writers like Joseph Beam were forgotten by history.

“It’s amazing, amazing to see these Black gay men spill their stories on the page,” Cooper said of Beam’s work Brother to Brother. “About masculinity, and femininity, and what it means. To navigate things in New York, and to navigate things in San Francisco … just trying to exist where you’re told you don’t belong.”

Salwa Abdussabur and Ala Ochumare. Later in the day, Ochumare helped assemble an altar to those who had been lost.

Salwa Abdussabur and Ala Ochumare. Later in the day, Ochumare helped assemble an altar to those who had been lost.

The timeline is ongoing, Cooper said. They pointed to “current changemakers who are in the space now, doing work.” To a chorus of mmmhhhmmms and yes I love her!, they noted Laverne Cox, the first Black trans woman they’d ever seen on T.V.—who could “act her ass off and serve you a look while doing it.” Or Native director and filmmaker Sydney Freeland. Or actor Jamal Lewis, who is working on a documentary called No Fats, No Femmes. The list went on.

From the back of the room, Soto hopped on the Cox bandwagon, asking campers if they’d seen her 2014 interview with Katie Couric. In the clip, Cox corrects Couric after a question on another trans woman’s bottom surgery.

“It was great,” he said.

But it was that first stop in Harlem that held campers’ attention. As Cooper had described the writer Wallace Thurman’s home in Harlem, dubbed the “Niggerati House” among circles of writers, poets, and painters of the period, students had come alive, eyes open wide for the durst time that morning.

Taylin Santiago and Narlin Chimbo.

Taylin Santiago and Narlin Chimbo.

“They would show up at this house for weeks at a time, be queer as hell, have gay sex, and lesbian sex and all the sex and they would write, create,” Cooper said.

They began to list works that had come out of the house. For instance, had campers heard of Zora Neale Hurston’s book Their Eyes Were Watching God?

“Wait, she was queer?!” asked Joseph, leaning forward on one of the center’s big couches.

“Very,” cut in Ala Ochumare, founder of Black Lives Matter New Haven.

“I’m sorry, I’m really shocked by this,” said Joseph.

“Zora Neale Hurston did it all,” said Cooper. “And then there was Langston Hughes …”

“Wait! He was one of our people?” Joseph cut in again.

“Queer as hell,” laughed Cooper.

“James Baldwin is gay too,” offered Narlin Chimbo.

“Jimmy Baldwin? Father Baldwin?” Cooper said, a smile tugging at the edges of their mouth. “Oh, he’s on the list too, trust me.”