Bill Kraus | Economic Development | Papier Mache Video Institute | Architecture | Arts & Culture | New Haven | New Haven Clock Factory

Bill Kraus in the factory earlier this month. He called his long relationship with the building "A labor of love, sometimes unrequited." Lucy Gellman Photos.

Bill Kraus in the factory earlier this month. He called his long relationship with the building "A labor of love, sometimes unrequited." Lucy Gellman Photos.

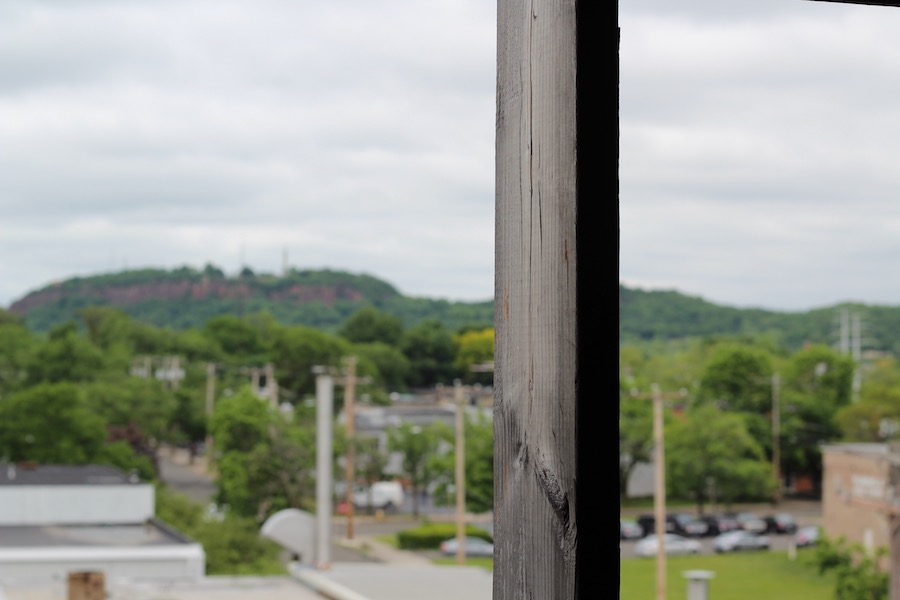

There are memories swirling through the New Haven Clock Company. They slither into crevices and over floorboards. They climb their spindly, dust-covered fingers up the walls. And through their thick fog, Paul Rutkovsky remembers walking in each day to do his work, and feeling like anything could take place there.

Rutkovsky is the founder of the Papier Mache Video Institute, an art incubator and artists’ collective that lived in the lofts from its founding in 1977 to the late 1980s. Earlier this month, he was one of several artists returning to the Hamilton Street building to speak about his history there—and a few of its ghosts—before it is sealed for remediation this weekend.

The project, with documentary photography from Meredith Miller and Hillary Charnas and filming from Gorman Bechard, is the brainchild of historic preservationist Bill Kraus. After becoming familiar with the building through the family that has owned it for decades, Kraus has helped push for its renovation and reuse as a space for affordable artists' housing.

His attempts have been partially successful. Earlier this year, city official approved the project, with a 15-year tax abatement (read about that here). But their agreement came with a compromise: only 44 of the building’s 130 units are slated to be reserved for artists. All of the units will be affordable housing, meaning they’ll only be open to people making 80 percent of what is called the Area Median Income (for more on AMI click here).

After years of environmental studies, the building is set to enter the first stages of a $6.6 million environmental remediation at the end of this month. It has been accepted into the state’s Brownfield Site program, a collaboration between the Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) and Department of Economic and Community Development (DECD). When asked, DEEP representative Mark Lewis said that the remediation could take a number of years.

When the remediation is done, Oregon-based Reed Realty Group plans to turn it into housing, only about a third of which will be reserved for artists and arts professionals (read about that in the New Haven Independent here, here and here). But before it undergoes that facelift, Kraus said he wants to talk to those who know its past lives better than he does, that their memories might inform its present, and future.

“The building has this unique, amazing, colorful history,” Kraus said by phone, in the midst of reaching out to artists to speak about their history at the building. “All the buildings I’ve worked on have had hundreds of years of history and lots of stories, but I’ve never encountered a history like this … it’s something that seems to need to be recorded before the building gets renovated.”

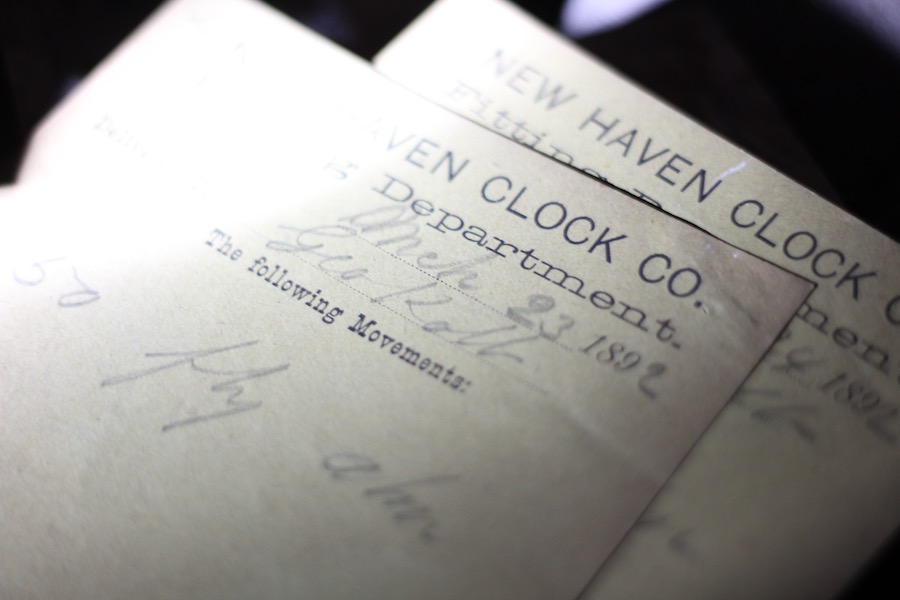

In its current form, the project will become part of a long and still-evolving history of the building that includes artist spaces, music clubs, strip and motorcycle joints, and a marijuana grow house busted by the Drug Enforcement Administration in the early 2000s. First constructed by clockmaker Chauncey Jerome in 1842, the factory became a bustling hub in New Haven, employing new immigrants as the Jerome Clock Company pumped out over 150,000 clocks per year. But the building’s wooden architecture ultimately posed a problem: it burned down during a fire in 1866, just two years before Jerome’s death.

It went on to be rebuilt in stages. Operated by Jerome’s nephew Hiram Camp and later Hiram’s son Walter, it reached the height of its production as the New Haven Clock Company in 1935, employing over 2,000 people and producing over three million clocks and watches per year. Like other clock and watch factories of the period, Kraus said the operation may have employed its own “radium girls,” the remaining presence of which has made the space a candidate for environmental remediation.

What remains of Hiram Camp's executive office.

What remains of Hiram Camp's executive office.

By the 1950s, demand for the factory’s clocks and watches had slowed, and the company shuttered its operations. The building wasn’t abandoned for long: one wing became occupied with a rotating slate of music venues, including a club called Brick 'n' Wood that housed R&B, punk, death trash metal, and grunge during its lifespan. As the space’s popularity grew, it brought in artists like Freddie Jackson, Evildead, D.R.I., Corrosion of Conformity, Gwar and others. In Brother West: Living and Loving Out Loud, a Memoir, Cornel West writes about dancing there with bell hooks in the early 1980s, when the two were working together at Yale.

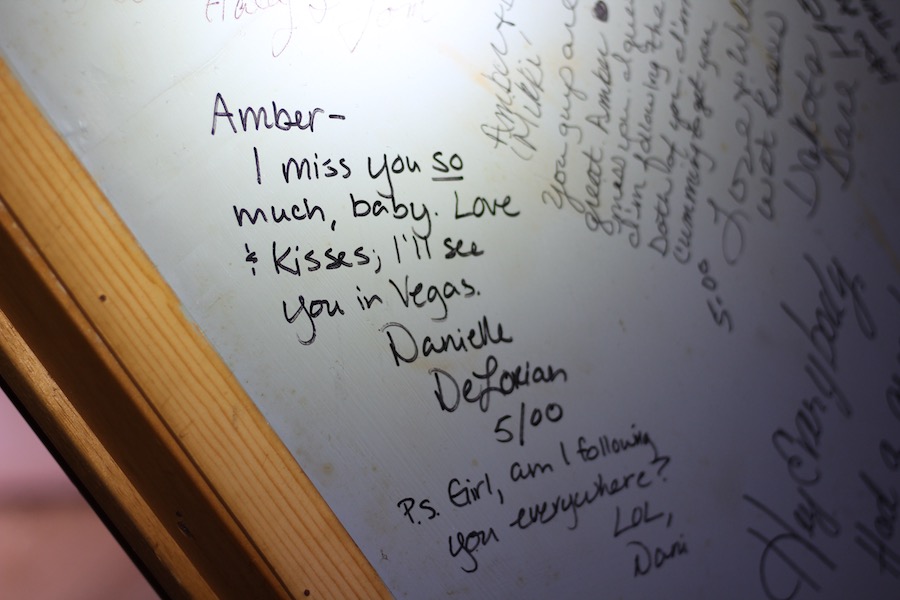

Other spaces cropped up around it. In what is now the gentlemen's club Scores, there was a gay club called Kurt’s 2, with a strip joint on the floors above it where feature acts left love notes to each other on the walls. On the second floor, the building housed the motorcycle gang the Bad Ass White Boys, with Bad Ass White Boy graffiti painted on the walls, and a Bad Ass White Boy code of conduct left on a counter when the group vacated the space. One floor up and further into the building, the Yale School of Architecture used the space for its famed Beaux Arts Balls, decorations still winking out from the walls. In a jerryrigged loft space nearby, one of the neighborhood’s thrasher musicians built a skate park complete with a half pipe (watch a video of skating in the building here).

One of the drawings remaining from YSOA's "Sex Balls."

One of the drawings remaining from YSOA's "Sex Balls."

Meanwhile, artists moved in on other floors, closer to the Hamilton Street entrance to the building. There was Rutkovsky, who worked closely with assistant Sermsai Snidvongs and handful of local creatives. Fellow artist Dimitri Rimsky gave birth to an illegal mime colony that lived there, setting up its own plumbing equipment where there was none, and remaining until a fire in the 1990s. On now-creaky and even sinking floorboards, the group hosted shows, facing a swath of the New Haven Public with no words at all.

Now, Kraus said, he’s trying to bring back several musicians, artists, and patrons who knew the space during that creative period of its life, as well as any living New Haveners who may have worked at the factory before it closed. Earlier this month, he kicked off the project with Rutkovsky, Rimsky, former Arts Council Executive Director Frances “Bitsie” Clark and former Arts Council Director of Communications Beverly "Bev" Richey. He said he is hoping to continue it during remediation and renovation.

“It Was Mind-Expanding”

"It’s like being a child, when you have the context, and the context is infinite possibilities. And I’m given that opportunity. It was just extremely exciting.”

"It’s like being a child, when you have the context, and the context is infinite possibilities. And I’m given that opportunity. It was just extremely exciting.”

In the factory’s sun-soaked parking lot earlier this month, Clark said she sees the building’s transformation into affordable housing—even if just a third goes to artists—as long overdue. During her tenure as director at the Arts Council of Greater New Haven, she watched as architects of the Audubon Arts Corridor promised to build affordable housing, then insisted that they couldn’t afford it. Years passed. She’d watched later attempts, including Westville’s ArLoW units—without great success.

“We’ve been talking about this for 30, 40 years,” she said.

Rutkovsky said he thinks it’s high time for affordable artists’ housing, too. Sitting outside the building after a walkthrough of his old stomping grounds, Rutkovsky said he can still remember starting operations in 1977. The building was populated, if not well: a man named Al Gabrer had a stained glass studio downstairs. The painter Kyle Staver, who is now in New York City, had a studio next to his. But the fourth floor was largely vacant, which was exactly how he liked it.

“It was mind-expanding,” he said. “It just left me excited, because Toni [Yagovane, who owned the building] … gave me free range. It’s like being a child, when you have the context, and the context is infinite possibilities. And I’m given that opportunity. It was just extremely exciting.”

Rutkovsky and Clark reunited.

Rutkovsky and Clark reunited.

He said he loved the building’s location, close enough to New York City and Boston that artists from both places would come and visit. And he loved his ownership of it—the door through which he entered read “PMVI,” and he felt as if it were his own. In 1980, he developed an act called “Mysterious, Serious Fires,” set on a stage with a black polyethylene proscenium.

On the stage were three mounds of white sand, a cardboard house, and cardboard car. Behind the screen, Rutkovsky operated a propane tank marionette, guiding the audience through parallel storylines on the house, the car, and a cardboard airplane that threw in. Then he burned the first two onstage. Snidvongs sat under the stage with matches, ready to ignite the figures if the marionette didn’t work.

“I was not thinking about suicide,” he said, chuckling a little. “But it was stupid for sure … I think about how crazy it was to do that. And it did fill up with smoke.”

Now, he said, he hopes that local artists are able to experience the space in the same way. Now a professor in Florida, he has started The Plant, a rehabbed industrial building turned creative space, where artists can work for free. He did note that The Plant is not exactly the same thing: it is a work space with no accommodations for living, and it is run entirely by volunteers.

Where feature acts left little notes to each other.

Where feature acts left little notes to each other.

“What is the definition of art?” he asked aloud. “Is it for just a certain group? In my opinion, art is for anyone, everyone. I believe everyone has a creative impulse … art is for everyone. And if you don’t make housing affordable, you’re screening out the creative impulse to explore, and to be humane. Exploring and creating is a humane act. It’s who we are.”

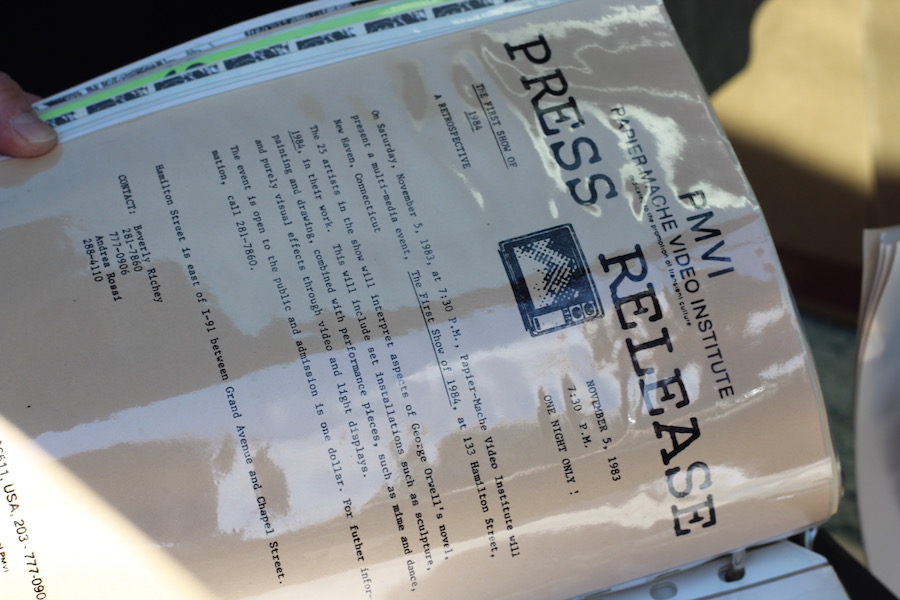

There from Milwaukee, Richey also returned to the factory earlier this month with binders and scrapbooks commemorating the work that both PMVI and Arts Council of Greater New Haven did in New Haven in the 1980s. A mentee of Rutkovsky’s, Richey took over the PMVI in 1982, when he left for a teaching position in Florida.

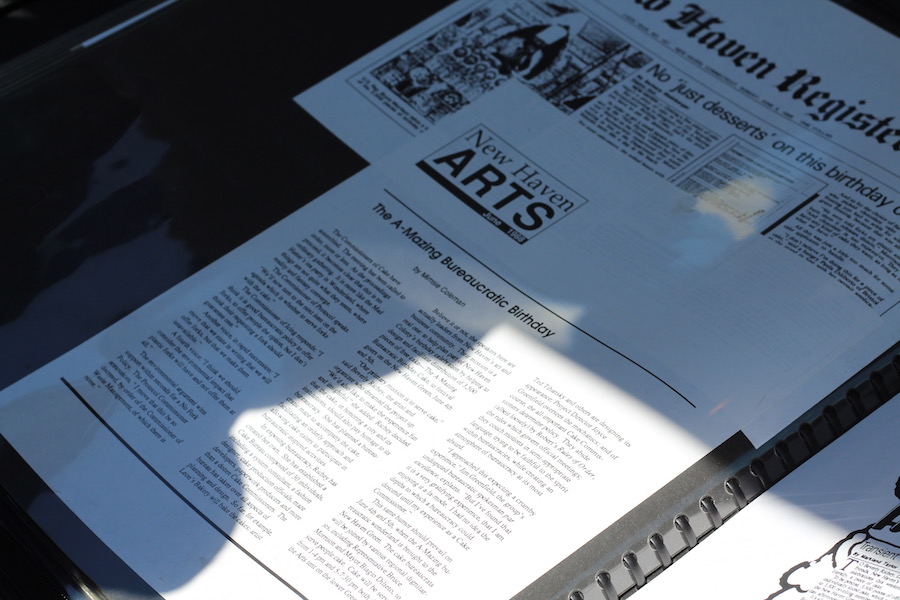

During the day, she recalled, she would plow through her work for The Arts Council of Greater New Haven, adding photos and regional arts events to its then-small print newsletter. Then at night, she would head to PMVI, and work doggedly on projects there. Her ministry was cake art—long before the first Edible Book Teas or Great British Bake-Offs ever took place.

In November 1983, she and artists in the collective gained regional attention with The First Show of 1984, a one-night exhibition (entry fee: $1) at the factory intended to pay homage to George Orwell’s dystopian fiction of the same name. With artists including Tim Feresten, Andrea Rossi, and Beverley Eliasoph—names that have now faded from New Haven history—Richey baked and assembled what the New Haven Journal Courier described as a “massive military cake with rewrapped Hershey bars.”

Clark and Richey. “We’re losing what it means to bake a cake,” Richey said.

Clark and Richey. “We’re losing what it means to bake a cake,” Richey said.

“That launched it into something where New Haven was doing something different,” she said.

Richey said it was the first of several edible statements for which the factory and PMVI were her creative springboard. At the Arts Council’s annual arts awards at Long Wharf Theatre in 1984, she rolled out a huge confection titled “Eat Audubon Street,” her response to the news that the Audubon Arts Corridor’s housing stock (now the Audubon Court Condominiums) would not be affordable after all.

And in 1988, she was commissioned by the city of New Haven to envision and serve a massive cake on the New Haven Green on July 4 and 5, during the city’s 350th birthday party. Naming it the “A-Mazing Bureaucratic Birthday Cake Birthday Cake,” Richey designed it with a maze, then brought a cake commission to perform “bureaucratic duties” onboard. Over two days, she served an ostensible 3,500 pieces to New Haveners (read more about it here and here). The following year, she left New Haven.

“When we cooked, we were all doing art,” Richey said. “We were all living creative lives … you gotta mellow down, you gotta quiet down, and then the juices start flowing. It’s a chemical thing. It’s not all hype and intensity.”

“We’re losing what it means to bake a cake,” she added. “We’re losing what it means to draw a picture. What it means to engage in ways that actually release stress … and when we take that away from the people, we’ve cheated everybody.”

But when it comes to artist-specific housing, Richey said she feels more complicated.

“I have issues around artists getting special privileges in that way,” she said. “This was a problem in the 80s in New York … if this space takes off, it’s going to be highly desirable easily in seven years, and the artists are going to be out of a place to live again, as well as the income-protected people.”

“Really, they’re there to gentrify the neighborhood and then move on to another neighborhood?,” she said. “That’s not pretty. It’s got to be protected. It’s got to be protected.”

That protection isn’t far from Kraus’ own hope for the factory, as he works to reshape the public’s understanding of what—and who—an artist can be, and how the building stands to expand economic development in the city. After supervising the rehab and development of several historic sites into artists’ housing, Kraus said he sees great potential in the building as a haven for artists of color who have been systematically cut out the discussion of who gets to make, consume, and have access to art. He added that the building has immense potential as an engine for economic development, serving not just the artists who live there but the city as a whole.

Kraus in the building earlier this month. Pictured is what he thinks was at one time an illegal skate park.

Kraus in the building earlier this month. Pictured is what he thinks was at one time an illegal skate park.

But that isn’t how city officials have discussed the project in the past months. Earlier this year, both Kraus and Reed Realty representative Joshua Blevins watched as New Haven’s Board of Alders and City Plan Commission asked whether artists were deserving of special housing stock when so many residents of New Haven may be in need of affordable housing.

The nuance, Kraus said, is that the two groups have overlap. Many artists are underpaid or contract educators who work in schools, hospitals, museums and recreational centers during the day, hone their craft at night, and still struggle to make ends meet. He said that’s particularly true for artists of color, mentioning New Haveners Sharece Sellem, Kyle Kearson, Paul Bryant Hudson, and Catherine Cazes-Wiley as he spoke.

Noting his previous work on Read’s Artspace (formerly Read’s Department Store) in downtown Bridgeport, he suggested that the lofts could the lofts could have a larger economic and creative impact on the community, because New Haven’s artistic community is already thriving in a way that Bridgeport’s may not be.

“There are a lot of artists of color in New Haven and they’re interested in coming here,” he said. He added that affordable housing in the building would give them “a stable, supportive platform, and visibility.”

“It’s been a labor of love,” he added of the building. “Sometimes unrequited.”

To check out a photo gallery from the walkthrough, click through the images below: