Film | Greater New Haven | Arts & Culture | Nasty Women New Haven | New Haven Fr

Shane Baber: “I didn’t see straight men stand up and say ‘this happened to me.’” Lucy Gellman Photo.

Shane Baber: “I didn’t see straight men stand up and say ‘this happened to me.’” Lucy Gellman Photo.

Shane Baber was 14 the first time he was molested. The perpetrator was an older man who had stepped in after his dad split. It didn’t feel right, but he thought that guys didn’t report molestation. It would be over 20 years until Baber decided he wanted to tell the story to a half-full room of strangers.

But does it belong in the #MeToo movement?

Baber brought that question to the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL) Thursday night, at the most recent screening of Nasty Women Connecticut’s #MeToo Testimonials Project. For months now, the organization has been collecting written, oral, and video testimonials from survivors of sexual harassment, assault and abuse.

Since holding an initial screening at Kehler Liddell Gallery in late May, the group has continued testimonial collection in the community, partnering with the Blue Encounters Community Arts Initiative and others. The project is funded by a Mayor’s Community Arts Grant from the City of New Haven.

Thursday marked the second in a series of summer screenings; the next is Friday Aug. 3 at Lyric Hall. All of them are free.

Lucy McClure: “We read magazines. We see movies. And we forget that these stories actually happen in our communities.”

Lucy McClure: “We read magazines. We see movies. And we forget that these stories actually happen in our communities.”

The evening was intended to be a 45-minute screening of the testimonials, followed by an audience discussion and narrative workshop by art therapist Mariah Gormas. But the audience discussion took over, with multiple questions from men in attendance about how to add male narratives to the #metoo movement in a thoughtful and deliberate way.

It started with the documentary itself, to which new stories have been added since its premiere. As Nasty Women Facilitators Lucy McClure, Louisa de Cossy and Attallah Sheppard introduced the project, they stressed that they see it as a work in progress, for which there is a more inclusive vision in the works.

“The reason that we’re doing the #MeToo testimonials project is that movements happen all over the world,” McClure said. “We read magazines. We see movies. And we forget that these stories actually happen in our communities.”

“We feel it is important to create that dialogue while lifting these voices—and create an opportunity for not only the survivors to tell their story, but also for us to think about ways to make sure these stories no longer exist,” she added.

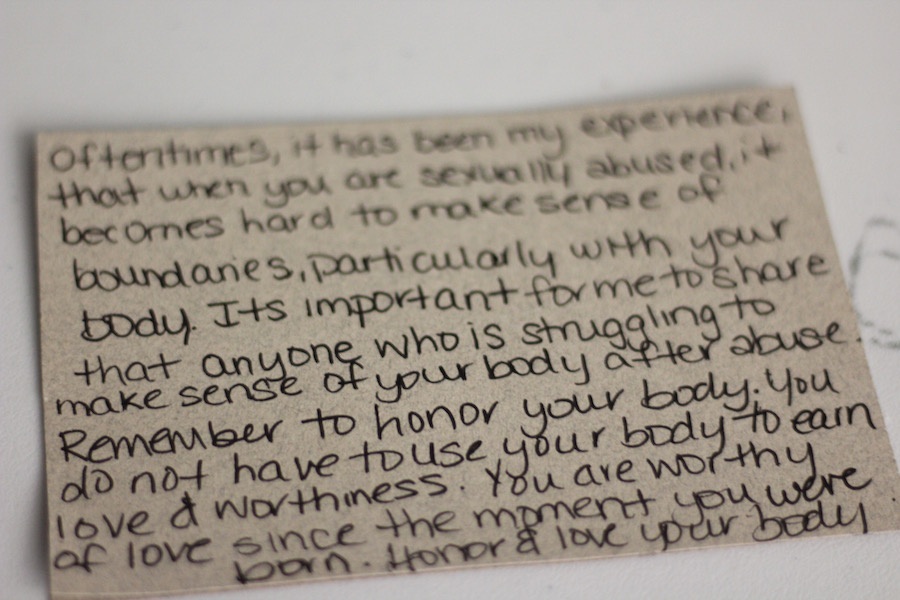

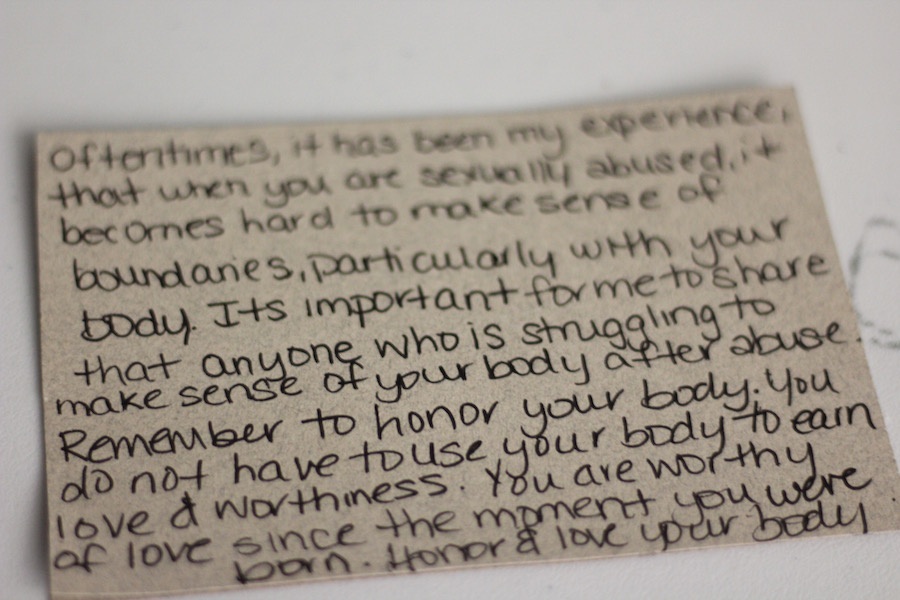

Part of a narrative workshop that followed the screning.

Part of a narrative workshop that followed the screning.

As the lights went down, Baber and his fiancee Diane Burzynski took their seats at the back of the room, joining a group of close to 15 that had gathered for the screening. At the front of the room the screen faded to gray, then sprang to life with artist Aly Maderson-Quinlog in a room at the Ely Center of Contemporary Art, looking at something beyond the camera’s lens.

She/they recalled working at a craft store in South Carolina 20 years ago, then just 18 years old. There was an older guy who lingered at the store, then the parking lot. One night, he followed her/them home. She/they drove away from him, and then notified a female manager. The manager took care of it—but Maderson-Quinlog was already suffering from the experience.

“I still to this day … I know like four or five routes to get home and I take a different route every time,” Maderson-Quinlog's voice boomed through the room. She/they recalled a day in Providence 20 years later, as a group of guys in suits followed her/them through the city until she/they ducked into a coffee shop.

“I just am who I am, and I never know if its going to be [a cause for] violence,” she/they said to the camera.

At the back of the room, both Baber and Burzynski had begun to cry. As they kept their eyes to the screen, activist Vanessa Suarez appeared and began to recount a harrowing story: a sexual assault several years ago at the hands of her uncle. When she told family members, they refused to believe her. When she bought the story up to friends, they encouraged her to remain silent, warning her that it could hurt her family. There was, she felt for years, nowhere to go.

Louisa de Cossy .

Louisa de Cossy .

“I silenced myself,” she said. “Not wanting to feel it. Not wanting to believe it.”

It took Suarez time—and therapy—to get the help she needed. Now, she said, “I try to tell my story, even if the world might not believe me,” because “I don’t want to constantly live in fear.” Instead, she added, she’s hoping that the story can inspire other women and girls to come forward.

But there were new faces too: two men, both advocating for the inclusion of their #MeToo narratives by simply stating them for the camera. Born and raised in Connecticut, artist Daniel Eugene recalled getting bullied in high school, as a group of peers held him down and sprayed a fire extinguisher on him. What stood out, he said in the testimonial, was that he got the same punishment for screaming as his harassers did for physical harassment. At the back of the room, Baber leaned in and continued to watch with a sort of mesmerized horror.

Eugene was only one of the men who’d come forward for the project—for which Nasty Women representatives said they’re looking for several more. Looking straight at the camera, Emmett Burns recalled attending a Connecticut high school that wouldn’t recognize his transgender status, informing him that he would have to describe his pronouns to teachers, substitutes, and other educators himself. Only after he coordinated a protest and walkout with the school’s LGBTQ+ students did the policies start to change.

Emmett Burns with partner Adrian Nordgren.

Emmett Burns with partner Adrian Nordgren.

“I just remember being so in the closet that it was painful to exist,” he said. Not long after, he was sexually assaulted by someone who knew that he was still medially female, and would have to report the sex and name that were still on his birth certificate if he went to law enforcement.

Those stories resonated for Baber, who opened up as Nasty Women tried to create what McClure called a “platform of inclusion and safety.” Speaking from where he sat with his fiancee, he told attendees that he was a victim of sexual assault—he was molested when he was 14 years old—but has never felt like his narrative is welcome in the #MeToo movement. He said that he hadn’t planned on telling his story when he arrived at the screening, but was so moved by the film that he wanted to give his own testimonial.

“I ain’t even gonna tell my mother,” he said. “I’m just as scared as a man.”

He said he knows that men are raped and sexually assaulted—one in six, according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) and national nonprofit 1in6. But, he added, “I didn’t see straight men stand up and say ‘this happened to me.’”

Attallah Sheppard: The puzzle piece is here, how do we engage men?”

Attallah Sheppard: The puzzle piece is here, how do we engage men?”

Germano Kimbro, a social worker who has been out of work for four years, also asked what the role of men was in the movement. To a room that became tense at points, he described getting passed for promotions and jobs by women who he felt he had mentored. He called #MeToo a form of oppression, that puts men, particularly Black and Latino men, “low on the totem pole.”

“It’s been real difficult for me,” he said. “You can give everything you got and still come up short. I’m coming in emasculated.”

At the front of the room, Sheppard nodded as she took in his feedback. Then she made a suggestion: men could be part of the movement. But they needed to let themselves be vulnerable first.

“How many men are saying ‘Hey, I want to be a part of this?’” she asked the room. “That is just something we’ve battled with in the filming. The puzzle piece is here, how do we engage men?”

“Another thing,” she continued. “Let’s just claim it: race. We find that Black women, Black men don’t want to come forward. [They say] ‘That’s weak. We don’t want to do that. Keep that in the house.’ It takes a lot to talk about the fact that you have felt that as a man.”

“This is not a fight between men and women,” McClure added afterwards, while writing a notecard to add to the #MeToo archive. “It’s a fight to create a space where we all feel safe.”