Lucy Gellman Photos.

Seven-year-old Hala J. was drawing shapes out on a piece of pink foam. Three big elm trees sprang up. Her blue pen skidded across the surface. She began to speak a neighborhood into being. Grass. Tree. Trunk. Leaves. Street. New. Haven.

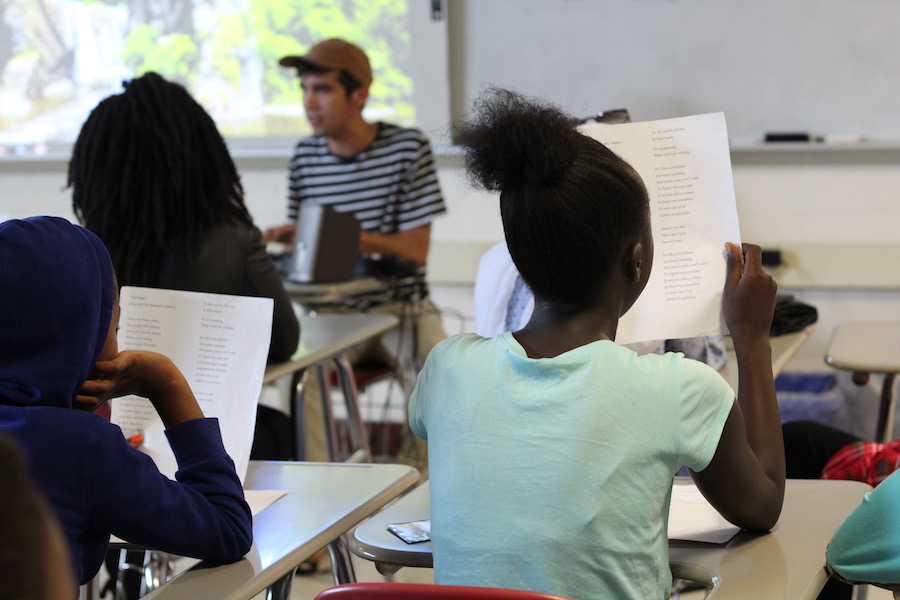

Hala, who came to the U.S. from Syria in 2017, is a student in Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services’ (IRIS) tenth annual Summer Learning Program, held June through August at Wilbur Cross High School. On Monday, she joined close to 70 students honing their English skills through collagraph printing, the latest chapter in language acquisition through academics and the arts.

Those 70 students—from elementary up through high school—are just part of the program. Each day through mid-August, Cross’ halls also welcome 30 moms and between 30 and 40 infant and preschool-aged kids through a summer extension of its Mother and Child English Program, more frequently referred to as ‘Mommy and Me.’ In addition to geography and language classes, the program uses visual arts and music as a way to practice English skills.

Sammy Colon (playing the piano at front) practices "Glorious" and "Let It Be" to students as a way to hone English skills. Music Instructor Jessie Griz has been leading that facet of the program.

“It’s just an active way to do it—to involve all the different senses,” said Ann O’ Brien, IRIS’ director of community engagement, as she popped in and out of classrooms Monday. “It’s all just trying to tap into the arts from different angles.”

She recalled watching students of all ages come in on the first day of the 2018 program, and stumble over the lyrics of The Beatles’ “Let It Be.” Now, she hears full-lunged refrains of “Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be/Whisper words of wisdom, let it be” in the hallways as students practice for an end-of-summer performance.

Born in 2008, the program was initially a sort of experiment with a small group of students and an academic coordinator at IRIS’ first Nicoll Street location. But as the organization has grown, so too has the program. In the past years, staff has limited enrollment to families who have arrived in the past 12 months.

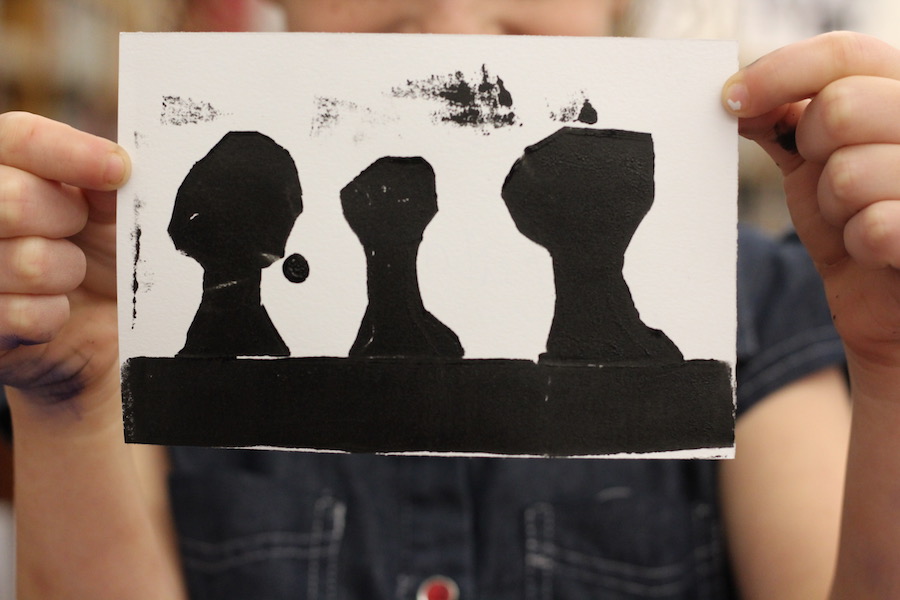

Roza's piece.

Then President Donald Trump’s travel ban drastically slowed arrivals to the U.S., a move upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in June. It's a landscape that looks drastically different than years ago, when the country had a limit on 80,000 refugees for that fiscal year (it settled closer to 61,000). A decade later, that number has been scaled back to 45,000 refugees and asylees, with a ban on people from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Syria and Yemen as well as North Korea and Venezuela.

That's changed the feel of this year's program, O'Brien said. While families are still arriving from Afghanistan, many on Special Immigrant Visas, overall entry and resettlement is way down. For the first time this year, IRIS has been able to invite refugees who’ve arrived in the past three years and two Guatemalan families referred to them by Junta for Progressive Action. O’Brien called it the only upside to the ongoing ban.

O'Brien added that the organization has also been working with Puerto Rican evacuees from Hurricane Maria, many of whom have taken advantage of English classes at IRIS' Nicoll Street offices and a new job resources point person based at Junta in Fair Haven.

Hala's design, before inking.

The approach trickles down to students including Hala, a chatty, freckle-faced 7-year-old at Beecher Street School who switches languages depending on who she’s talking to. As she took a seat with a handful of other kids, art teacher and Soul Haven founder Laura McGowan talked students through the day’s art activity, a collagraph print on foam and cardboard, with a few age-appropriate shortcuts.

“Show me where you live,” McGowan encouraged the students, lifting an image of a house with a sharp roof, surrounded by brownstones. “Show me your neighborhood. What do you see when you go out? What do you see when you take the bus?”

In Cross’ library-turned-classroom, students began sketching on foam, ready to affix it to cardboard “printing plates.” Strains of Arabic, Pashto, French and English bubbled up from the tables. Hala tilted her head one way and then the other, settling on a view that she sees from the sidewalk each morning. Three trees, with thick long grass in front of them.

A plate readied by Lulu A., who is from Syria and worked with an older age group. She said the piece was inspired by fireworks that she saw on the Fourth of July from her home in New Haven's Edgewood neighborhood.

“I like drawing!,” she said as she made quick pen marks for individual blades of grass. “It makes me happy. And I like trees.”

Beside her, 4-year-old Roza J. tied and untied a long bow on her flowery red dress, motioning for assistance as she struggled against the fabric. In front of her sat a half-done print, packed with small, floating shapes and ready for printing. She said the print, based on her interest in becoming a firefighter, reminded her of several picture books at home.

At a circular table, McGowan worked with students one by one to roll the plates with shiny, thick black ink and then do a relief print on white paper. A Connecticut native and former museum educator, she began her arts outreach a few years ago with ‘Soul Haven’ sessions in Stamford.

Laura McGowan: "It builds confidence, I think. I hope.”

She’s since expanded the program, taught on a completely volunteer basis, to libraries and nonprofits in New Haven. Each time she gives a lesson at the summer learning program, all 70 students cycle in and out of her classroom.

“I think for a lot of these students, there is a language barrier” she said. “Art transcends that. There is a lot of rigorous learning [in the program] and art is kind of an escape.”

She added that the group has been working on self-portraits, “so they know each other and they know themselves. It builds confidence, I think. I hope.”