Dreyfus Affair | Music | Afro-Semitic Experience | Arts & Culture

Warren Byrd leaned into the microphone, piano and upright bass slowing to a march around him. Horn and woodwind sounded somewhere in the near distance. A universe away, Impressionist Camille Pissarro was alive and losing his mind on the streets of Paris, vigilant as he trotted through the city’s grimy fifth arrondissement.

For the moment we have to deal with nothing more

Than a few Catholic Latin Quarter ruffians, Byrd sang as half-himself, half-Pissarro

They shout down with the Jews/But all they do is shout

They shout down with the Jews/But all they do is shout

The lyrics paint a scene from Letters from the Affair, a new project from artist David Chevan and members of The Afro-Semitic Experience that has been five years in the making. Based on France’s notorious Dreyfus Affair of 1894, the piece follows artists Camille Pissarro and Edgar Degas through the end of the nineteenth century, as their friendship is rocked, then destroyed, by the Dreyfus trials and a new wave of antisemitism in France. Degas believed that Dreyfus had committed treason; Pissarro did not. The piece will premiere at Best Video Film and Cultural Center in Hamden (BVFCC) on Aug. 16.

Soaked in historical context, Letters begins on the cusp of the twentieth century, in December of 1894. In Paris, French artillery officer and military captain Alfred Dreyfus has just been convicted of treason for leaking French information to German forces. Things do not look good for him: Dreyfus is a dedicated Frenchman and public servant, but he is also a Jew at a time of concentrated antisemitism in France (there is, arguably, never not a time of concentrated antisemitism in France), and becomes an easy target as the military searches for their infiltrator.

What follows is a story of insider baseball, military paranoia and political setups that resonate still: in 1895, Dreyfus was publicly shamed and stripped of his military titles based on scant evidence, then exiled to French Guyana until a second trial in 1899. In the intervening years, the trial, new evidence, and its aftershocks split the public sharply: supporters of Dreyfus maintained his innocence, while supporters of the verdict and exile decried him as a traitor. No social class was protected from the debate—especially artists, whose work shifted with and often engaged the political tides of the city.

That intrigue and injustice captivated Chevan nine years ago, when he picked up a book review by New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik. As he read about the book—Louis Begley’s Why The Dreyfus Affair Matters—he was shocked to find the affair had fractured the artistic community, including fin-de-siècle giants Degas and Pissarro. No sooner had he finished it than he was on the trail to discover as much as he could.

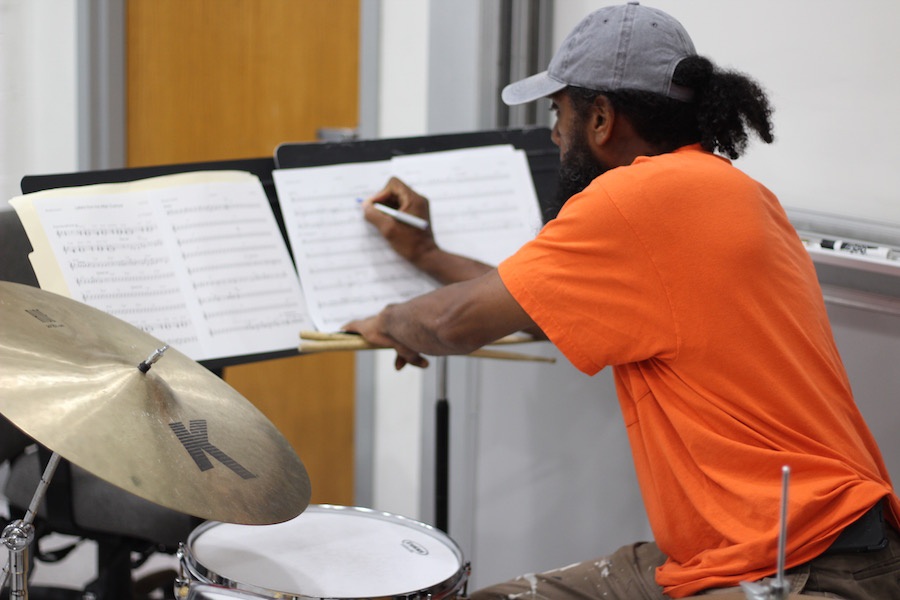

“I became really interested in [knowing] what is the story of these two artists,” he said at a rehearsal earlier this week, as the group practiced at Southern Connecticut State University. “Immediately when I saw that it was Degas and Pissarro … in their mature twilight years, I was like: ‘I know just the people who can sing this!’”

Chevan, who knows exactly enough French to say “I do not understand French” in French, tried several times to write a libretto himself, using a network of sources in translation to learn about the artists’ friendship and falling out. Each time, he recalled, it failed—something wasn’t right, and he would have to go back to the drawing board. Then one afternoon, he was reading letters from Pissarro to his son Lucien, and realized that the words for the piece were right in front of him.

Spurred onward by the election of Donald Trump in 2016, he finished composing earlier this year, then worked with musician Will Bartlett to arrange instrumental parts. As it stands, the cycle includes jazz, opera, klezmer, tango, and cantorial singing, as well as text and period art that will be shown on a PowerPoint timed with the music.

“When I read it, two things happened,” said drummer Alvin Carter, Jr., who does a 25-minute narration between the overture and the piece’s first movement. “I got really bent out of shape about the injustice of that particular affair, and then I got bent out of shape on a wider scale about all the stupid stuff that happened here on the continental United States to Africans in the Americas. Those stories are too numerous to mention.”

“People in general who were already generally racist are feeling more emboldened,” he added of the piece’s context now. “Every group that has a foot on their neck is feeling it.”

Indeed Letters is a thing of beauty, resilience and also fear from its overture, where the wail of a woodwind can expose a city’s darkest secrets. As Byrd takes a deep breath and begins to sing (“At The Inhalation”) we are pitched into a world where nothing is as safe as it seems. Piano rises to meet slow, mellow base and tremulous drums, horn and woodwind slip into the mix like whispers of something dangerous.

From that moment, no friendship is too sacred to last this debate. As “At The Inhalation” sets up the scene, a PowerPoint springs to life with covers of Paris’ daily illustrated newspapers, a central vehicle by which news of the trial traveled. Byrd’s voice, low and methodical, fills the room.

He’s a shape shifter: he can sing-whisper, howl, scat, and traverse octaves between pieces. In one letter from Camille Pissarro to his son Lucien (sent from Paris Jan. 31, 1898), Byrd turns the tender libretto into a rallying cry, giving a swooping shout on the words anti-semitic and later, a chorus of nothing inside. Horn and sharp woodwind march along under his voice, as if they are helping Pissarro walk along as he delivers the letter to the post office. While Chevan has stripped the letters to their cleanest and most poetic, we still get the gist: this isn’t a great time to be a Jew.

By the time the work shifts to Pisarro’s assurances to Lucien that he can pass as a non-Jew on his way to run errands through the city, we’re deep into the city, and the debate over Dreyfus’ innocence has become partisan, fanatical, and religious. Horn and screaming clarinet rise to a tango, bass comes in to keep time and move the story along. The tempo matches the time: Émile Zola has published his editorial accusing the government of conspiracy, cover up, and anti-semitism (“J’Accuse!”), and those against Dreyfus are livid. Byrd’s voice holds steady for a moment that cannot, fear creeping into its edges.

I found myself in the middle of a gang of ruffians

They shouted death to the Jews, down with Zola

They shouted death to the Jews, down with Zola!

I calmly passed through them

And reached the Rue Lafitte

They had not taken me for a Jew

There are moments, too, from the other side that bring us to our knees. In a subdued, closing piece, Degas recalls a strange dream that he has had in which Pissarro is still alive, and he can speak again to his friend.

The result is incredibly timely, with centuries-old words that could have been written this year, this week, this hour. It is not the first or most historically-minded piece to take on the affair (Michel Legrand and Didier van Cauwelaert premiered Dreyfus at L'opéra de Nice four years ago, following a small mountain of literature and art that’s been made on the case), but its resonances are deep and moving.

When Byrd sings “France is really sick/Will she recover?” his voice dipping tragically to horn and upright bass, it seems he could be talking about America, as white nationalists plan protests around the country. When Pissarro, a Sephardic Jew, walks through a gang screaming “Down with the Jew!” he is practicing a ritual of passing that both French and American Jews still practice today.

The worst of history, indeed, repeats itself. In that world, the affair fostered the same rhetoric that spawned the rise of Adolf Hitler in Germany, and the far-right Vichy Regime in France. In ours, whispers of anti-semitism multiplied around the Rosenberg Trials and Red Scare, and much more recently white supremacy and recent Q Anon phenomenon.

On the date that Dreyfus received his conviction, France was less than 25 years out from its loss in the Franco-Prussian war and ensuing Paris Commune of 1871, which led to widespread political paranoia, civil war, and mass execution from the state. We may not have an Émile Zola or an army of Dreyfusards, but we have Edward Snowden, and a body of truth-tellers now known as enemies of the people, all with targets painted on their backs.

It’s a partisan parallel, too, that encourages the audience to ask questions. Where, for instance, do we draw the line between political right and wrong? When do we question the government, and when do we trust it? For what cause are we willing to lose our friends? When do we start worrying that we are in danger?

And on which side of history will we all be remembered?