Design | Architecture | Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven

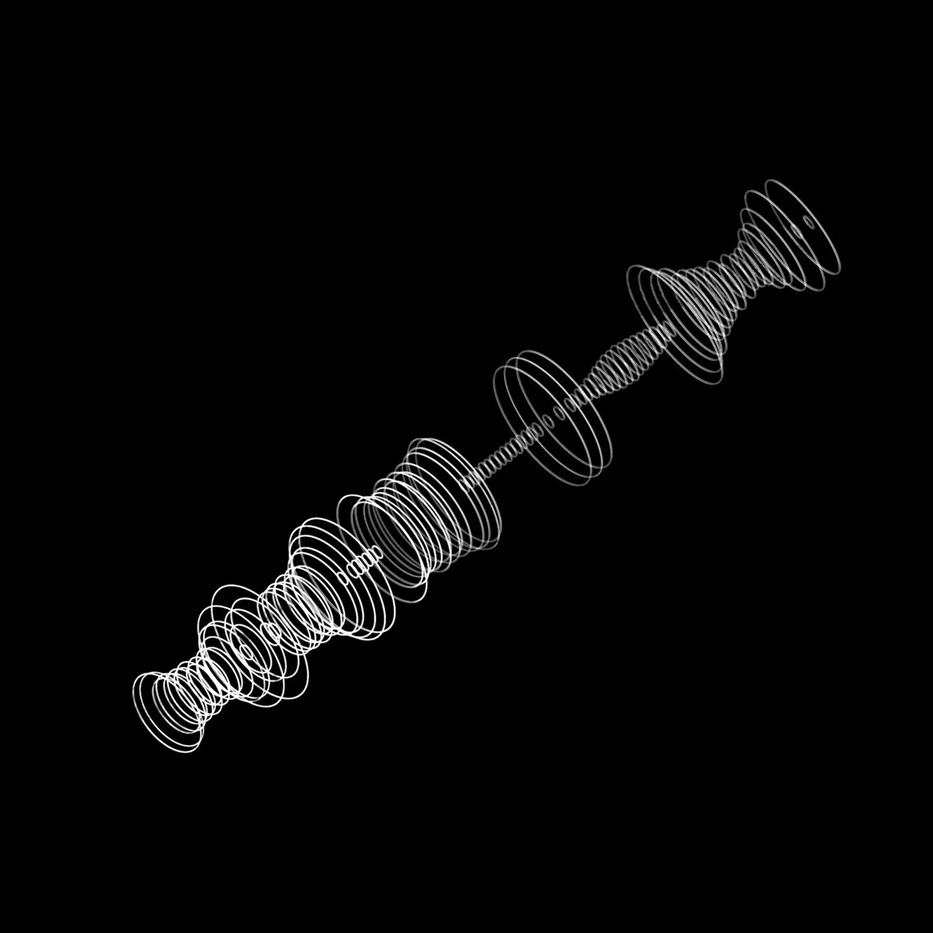

A still image of the video provided by Dana Karwas.

A still image of the video provided by Dana Karwas.

The white concentric circles emerge a few at a time and add up quickly. Soon, they are roaring with intensity, mimicking a ripple in a pond. Circles of different widths pulse across the entirety of the screen, reaching peak intensity. They recede inwards just as quickly as they expand, leaving only a black screen behind.

The video is an introduction to Dana Karwas’ In A Heartbeat, a three-piece exhibition running at Artspace New Haven through May 22. Karwas’ work is inspired by W.E.B. DuBois' short 1908 science fiction story The Princess Steel, particularly the “mega-scope” developed by the crank sociologist Dr. Johnson. In the story, a married couple looks through the “mega-scope” and are able to see through time and space. They catch glimpses of the invisible links in the world.

It runs in conjunction with W.E.B. DuBois: Georgia, and his Data Portraits and Theaster Gates: Light of Progress, both on view through June 26.

“How one person sees it might not be how another person sees it,” said Karwas, who serves as the director of Yale’s Center for Collaborative Arts and Media. “Sometimes a camera will see something and that person has to look at that isolated moment which can be incredibly consequential and devastating or other times can be beautiful.”

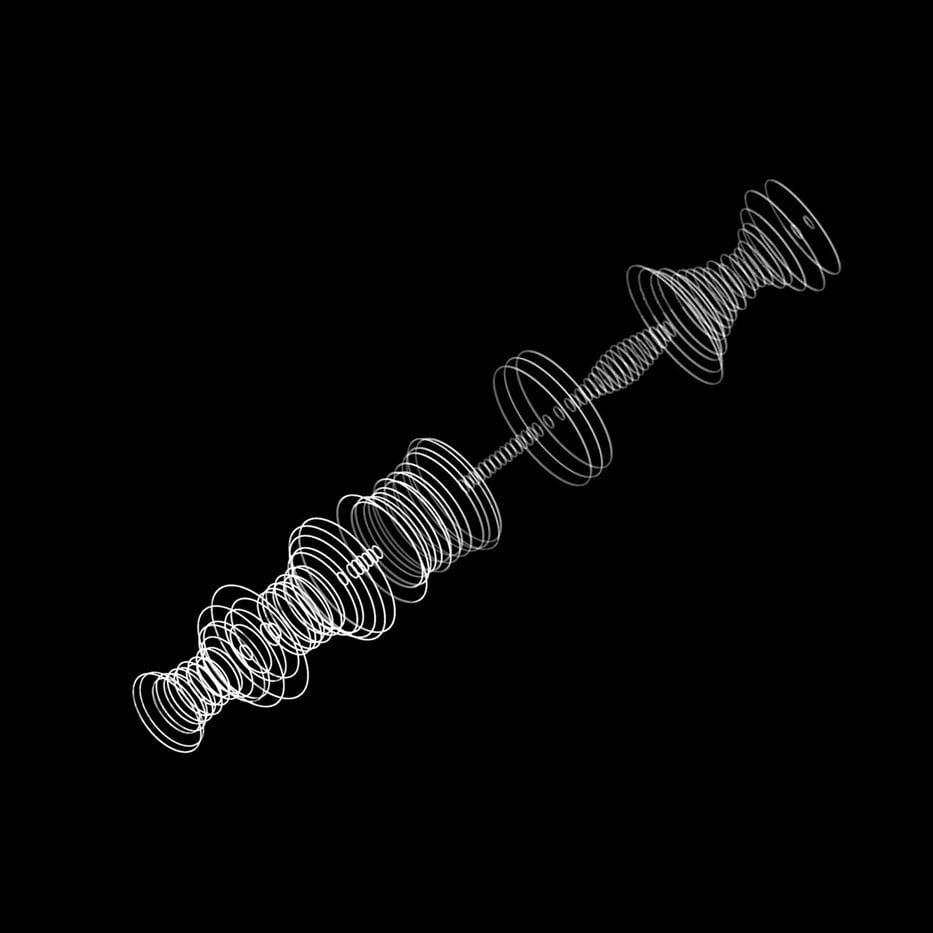

Counter Curve by Karwas. Arturo Pineda Photo.

Counter Curve by Karwas. Arturo Pineda Photo.

Karwas’ reference point for these invisible links is the human heartbeat—an occurrence that unites everyone, yet is mundane and inconsequential on its own. Per minute, there are more than 608 billion heartbeats in the world. The questions for her was what can happen in a split second of a heartbeat, and how artists can visualize that isolated moment.

To play with perspective and scale, Karwas converted heartbeat electrocardiogram (EKG) line readings into radial or circular visuals. There had to be a new and more human way to understand a heartbeat, she said. Medical staff can interpret these readouts with medical expertise, but “the feeling” of the heartbeat was lost in the process.

At one point in the video, the circles that are presented in a two-dimensional format are rotated, giving access to the view of a tower of circles one atop of another. With this shift, Karwas’ work showcases the belief that the greatest connections are aggregates of the most mundane and repeated actions. It is only through the constant accumulation of simple gestures that the overarching connections can be drawn.

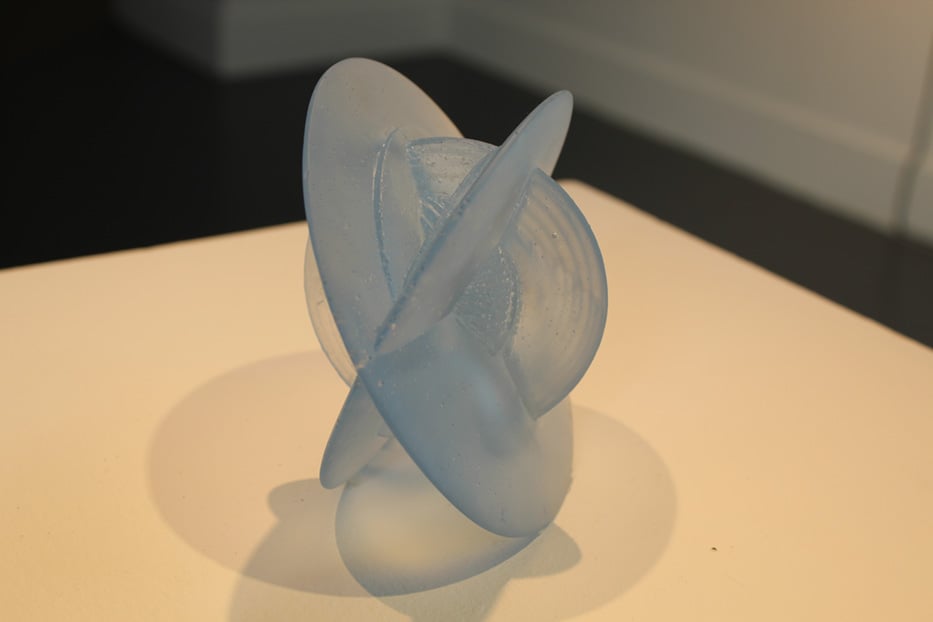

Orbital Axis by Karwas. Arturo Pineda Photo.

Orbital Axis by Karwas. Arturo Pineda Photo.

But neither humans nor their heartbeats are perfect. That truth is reflected in Counter Curve, a five-foot-in-diameter pumice disk engraved with another circulate heartbeat. In contrast to the video, these lines have a physical depth and roughness as a nod to the electrical wave currents that run through the heart. Karwas said she selected pumice because she wanted a material that could “feel like particles within the radiating structure of the heart.”

There are also dashes and spots outside of the lines, just as Dr. Johnson encountered it in developing the mega-scope. He kept encountering curves, counter-curves, and shadows of “human deeds” that he had not accounted for. It led him to the realization that those curves belonged to the higher beings, or the Overmen, who have shaped human existence.

Similarly, perspective and subject are distorted in Orbital Axis, a three-dimensional structure of a heartbeat approximately the size of a human heart. In this work, Karwas has mapped the electrical currents that run through the heart. Her orbital rings represent the various directions the electricity within the hearts takes.

By placing the smallest of gestures together, Karwas gives a new context to both that group of gestures and the original gesture itself. A heartbeat itself is not consequential, perhaps—but a tower of 50 or even a 1000 heartbeats is much more commanding. From the front-facing view it would be impossible to distinguish if the image is one or 50 heartbeats, empathizing that it is not the number of heartbeats, but the heartbeat’s occurrence itself that is most important.

Arc of Near by Karwas. Arturo Pineda Photo.

Arc of Near by Karwas. Arturo Pineda Photo.

The exhibit culminates in Arc of Near, a clock-like sculpture again depicting one heartbeat with a limited perspective. Two black glass disks sit atop one another. The bottom disk has dozens of coarse concentric white circles carved into it, but the top disk covers most of them. The top top disk slowly rotates, only showing glimpses of the curved white lines through a cutout.

“Whoever looks at this can see that it's a split second of a gesture over time, but you can never see it in full because the void keeps moving in the rotational structure so even the mega-scope can’t reveal everything to us,” Karwas said.

Karwas subverts viewers' expectations of the piece when she reveals that the center of the engraved circles is not in the center of the bottom disk. The off-kilter feeling to the work is a reminder that capturing isolating moments in a perfect frame of reference—a circle—is near impossible to begin with.

At the end of the story, Du Bois reveals that the husband was able to see through the mega-scope but the wife saw nothing. According to the doctor, it still needed further adjustment for her before she could see beyond.

“I hope this exhibition gives people the space to consider their own small moments—carefully,” Karwas said.

The exhibition Dana Karwas: In A Heartbeat runs at Artspace New Haven, 50 Orange St., through May 22.