Arts & Culture | Artspace New Haven | Ninth Square | Visual Arts

Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski.

In the sun-bathed front gallery of Artspace, viewers can now repose on uncommonly comfortable bean bag chairs. On a cafe table before the chairs are four ballpoint pens, unmarked copies of the exhibit’s germinal texts—Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth and Harsha Walia's Border & Rule among them—and an open invitation to annotate them. Hanging on the wall are prayer rugs, which in vibrant blocks of color convey steady messages: “I am a body,” “iamuslima,” and “I’m as good as you are.”

Baseera Khan’s Reading Room, on Purpose provides visitors with a moment of breath, spirituality, and study. It invites viewers to dwell in this resource of time.

Khan is an artist in Dyschronics, running at Artspace New Haven now through April 16. Curated by Laurel V. McLaughlin, the exhibition features the work of Carolina Caycedo, Emily Jacir, Baseera Khan, and Tsedaye Makonnen. The four artists share not only an interest in migration and diaspora, but also in time.

Time is of special interest to McLaughlin, whose background is in the time-based medium of performance art. Since her graduate studies at the Courtauld Institute of Art, McLaughlin has been studying time as it relates to migration. She is now a doctorate student at Bryn Mawr, about to defend a thesis expanding on this work.

Detail, Baseera Khan’s Reading Room, on Purpose. Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski.

Time seeps into the migration process in every which way, McLaughlin said in a Friday afternoon walkthrough of the exhibition. There’s the passage of time in detainment or in waiting to cross a border. The scholar Ranajit Guha’s term “temporal maladjustment" troubles McLaughlin because it depicts a waiting migrant as disempowered.

She draws instead on Miguel Á. Hernández-Navarro’s concept of “dyschronys,” a so-called “fourth time” that resists the Western construct of linear and monolithic time. Through it, she hopes to spotlight the ways in which alternative notions of time become the basis of protest.

As McLaughlin walked through the five galleries and one screening room last week, she pointed to the various instances of resistant time in each of the four artists’ work. There was the glitchy footage in Caycedo’s video installation To Stop Being a Threat and To Become a Promise, and the rest time evoked by Khan’s “Psychedelic Prayer Rugs.” There was the nonlinearity of Jasir’s documentary “letter to a friend.” Makonnen’s Astral Sea textiles, which McLaughlin mounted with creases, literalize the folds in time.

The works in Dyschronics build upon one another, suggesting that time is a medium that can be activated, used and misused, and molded and manipulated to one’s purposes. Time can be used for resistance, protest, and revolt.

Detail, Khan’s Purple andBlack and House I and Love Ceremony. Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski.

Time is also the conceptual thread joining the four artists’ work together. So, too, is the documentary impulse in the work of Jacir, Caycedo, and Makonnen.

Jacir’s letter to a friend painstakingly documents her historic, 19th-century family home in Bethlehem, which Jacir predicts will imminently be occupied by Israeli settlers. Jacir gathers evidence to send to her collaborator, Forensic Architecture, a research group that specializes in the investigation of human rights abuses, to preemptively investigate the Israeli occupation.

The evidence Jacir gathers is as specific as the number of steps it takes her to reach Israel’s separation wall—alternately referred to as an apartheid wall or a barrier depending on who is writing the narrative—which violently bifurcates the West Bank. “On some days, it is around 220 steps,” Jacir says in the voiceover. “And, on others, it is around 210.”

The accompanying gallery displays still images from the film. Printed on an aluminum that creates the effect of a matte finish, the stills appear stripped-down and unembellished. On one hand, the images appear forthright, immediate, ongoing. On the other, they appear almost archival. It is a fitting evocation of a conflict whose timeline has been compacted into a single point, such that, based on past and present evidence, Jacir is already able to predict the future.

Top: Detail of stills, Emily Jacir's letter to a friend. Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski. Bottom: Detail, Carolina Caycedo’s Serpent River Book. Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski.

Caycedo’s BE DAMMED, like Jacir’s letter to a friend, gathers evidence to document past, present, and future harm. The portion of BE DAMMED on view at Artspace centers on the damming of waterways by transnational corporations in Colombia, Brazil, and Mexico.

Caycedo’s evidence comes in the form of a dual channel video installation To Stop Being a Threat and To Become a Promise. In a clip in the left channel, a child swims across a crystalline body of water, their long hair trailing in their wake. The exquisiteness of the moment is juxtaposed against a clip in the right channel, which displays a bold-face sign that reads: “Keep Out.” Caycedo applies a kaleidoscopic effect to this clip. The single sign multiplies into eight signs, expanding and contracting in dizzying repetition.

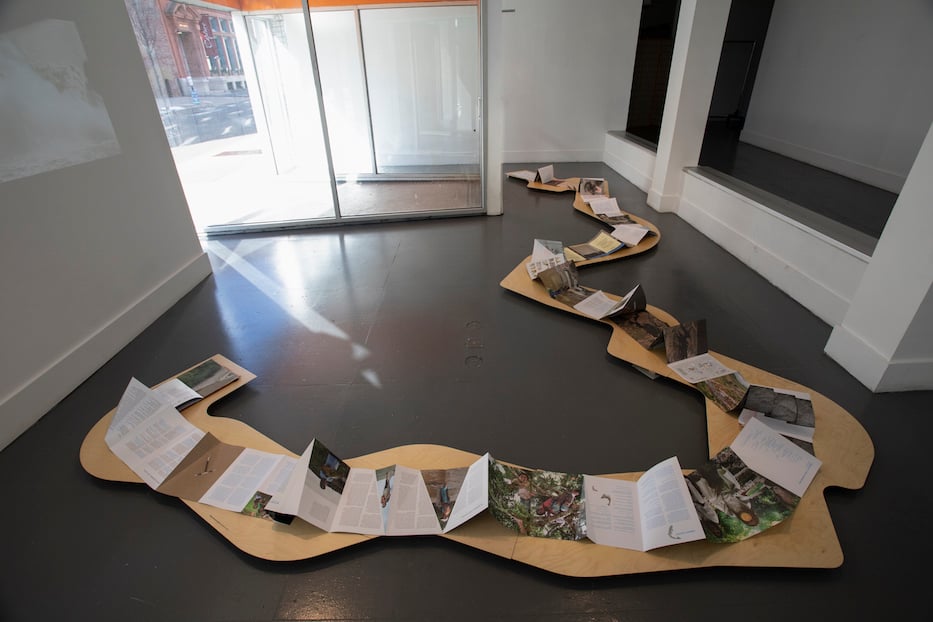

Detail, Carolina Caycedo’s Serpent River Book. Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski.

Evidence also comes in the form of an experimentally designed Serpent River Book, whose pages contain dozens of unpredictably placed folds. Mounted on a honey-colored wooden track that loops and bends to resemble a natural waterway, the book can be unfurled in hundreds of different permutations. Moreover, the book can be read forwards or backwards, in English or Spanish, and through text or pictures.

The viewer receives this evidence as if it were a puzzle with minimal rules of engagement. Perhaps Caycedo is directing the viewer to engage with the evidence in any matter of ways they so please—there is no single correct way. Or perhaps Caycedo is making the viewer’s engagement purposefully involved, such that they must stoop to the floor and, neck craned, attempt to read the pamphlet.

Serpent River Book’s current installation, on a track less than a foot above ground level, makes doing this difficult. McLaughlin has scheduled a workshop to allow visitors a closer engagement with it.

Detail, Tsedaye Makonnen’s “Astral Sea” series. Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski.

The documentary impulse occurs yet again in Makonnen’s three-channel video installation that accompanies the display of the Astral Sea textiles. In the background of the left-most channel looms the rusted and faded ruins of a now-infamous fishing boat, which in 2015 sunk and killed up to 700 Libyan migrants en route to Europe. The Swiss artist Christoph Büchel appropriated the ship and displayed it without context in the 2019 Venice Biennale, spectacularizing the deaths of Black people.

Through ritualistic performance, Makonnen returns dignity and humanity to the Black people lost in the wreck. Sheathed in her ceremonial textile crisscrossed with reflective geometric patterns, Makonnen beats the ground with the textile over and over, performing a somatic ritual of her own creation. The emerald blue fabric collides with the dirt, each physical impact indexing the lives lost.

For the gallery viewer, however, the act of spectatorship turns complex. Onscreen, an endless stream of white people—some tourists, some locals—gather around and gawk at Makonnen. A young man stands transfixed in the video’s background, his eyes locked on Makonnen for an extended stretch of time. The people around him move onward and still he remains. Another man approaches Makonnen and begins to argue with her; it appears he is forcing her to leave.

Detail, Tsedaye Makonnen’s “Astral Sea” series. Installation View Dyschronics, Artspace New Haven, February 11–April 16, 2022. Photo: Jessica Smolinski.

The spectators crowd the frame, becoming as much of the channel’s subject as is Makonnen, the ritual leader. The spectators’ presence is magnified by the projection’s size and placement close to the floor: they become life-size and seem to extend into the gallery space. The “fourth wall” of the exhibition room becomes folded into the space of the projection. Time folds as well: in the present, the gallery viewer has the potential to participate in past spectacle, to add onto it. The viewer’s spectatorship thus becomes risky.

The question arises: how can one spectate, without spectacularizing?

Through folds in time, Dyschronics transports the viewer to the ever-expanding present moment of crisis. It also leaves the viewer with the sense of time as a tool of empowerment.

Although the exhibition has no plans to travel, McLaughlin has planned an extensive schedule of workshops, lectures, and performances to accompany the exhibition. In particular, there is an artist lecture, in partnership with Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS) and Bregamos Community Theater, planned for members of the New Haven migrant community, and a closed-registration workshop for Eritrean migrant women with Dawit L. Petros. The programming schedule is forthcoming.

Dyschronics runs at Artspace New Haven, 50 Orange St., through April 16. The gallery’s hours are Wednesday through Saturday, noon to 6 p.m. Learn more at the organization’s website.