Music | Southern Connecticut State University | Arts & Culture | New Haven Symphony Orchestra | Whalley/Edgewood/Beaver Hills

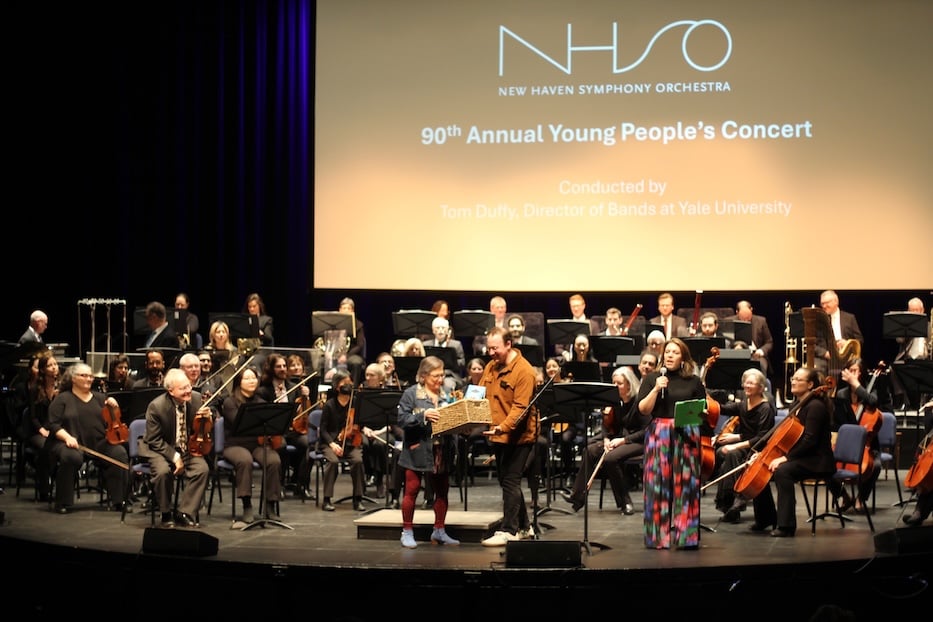

NHPS' Ellen Maust, who will be retiring this year, receives recognition from NHSO Operations Director Jeremey Lombard. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Strings jolted the audience awake, cellos singing their low-bellied hello to the violins. Viola glided in behind them, the sound sailing into the front rows. Above the musicians, an animated star catapulted through space, shedding pinpricks of violet light as it traveled.

On the edge of their seats in Row O, seventh graders Rhayn and Kelly sat transfixed, imagining galaxies they’d never seen before.

Tuesday afternoon, the two were among hundreds of New Haven Public Schools students at the New Haven Symphony Orchestra's (NHSO) 90th Annual Young People’s Concert, held at the John Lyman Center for the Performing Arts at Southern Connecticut State University (SCSU). Designed to introduce students to live music, the performance included selections from Georges Bizet, Jessie Montgomery, Antonín Dvořák, Paul Dukas, Amanda Harberg and Russell Peck.

In an era that is increasingly digital, it became part rock concert, part close listening session and part prayer, students slack-jawed and wide-eyed as musicians took them on a journey through time, space, and sound.

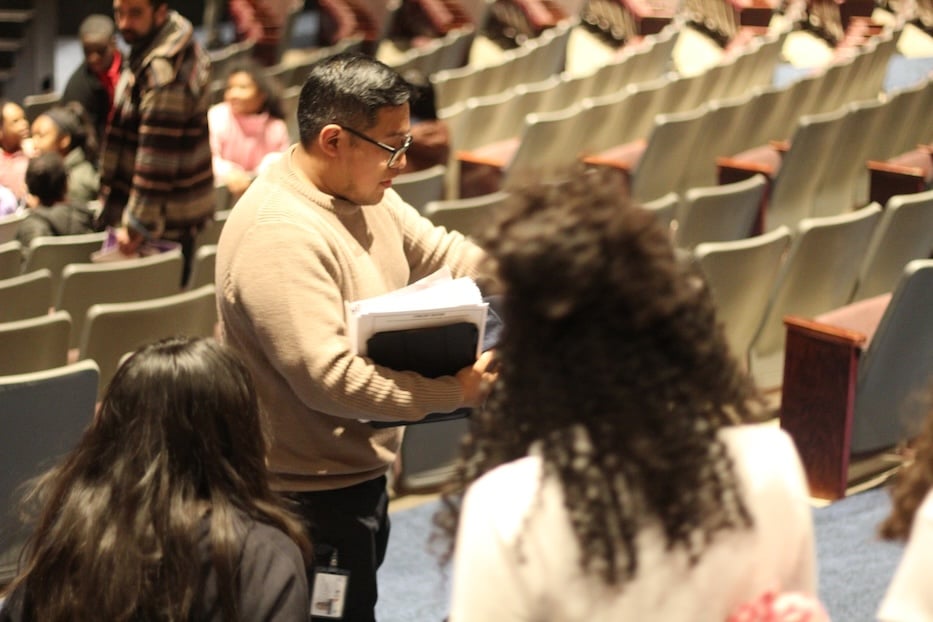

“It’s just amazing,” said Eliel Martinez, a music teacher at Fair Haven School who resurrected the band when he arrived last year. Behind him, two dozen students filed into their rows, English and Spanish drifting through the space as they chatted. “I’m so happy to have them watch these musicians.”

Composer and NHSO Operations Assistant Damali Willingham narrates Russell Peck's "The Thrill of the Orchestra."

From the moment lights went down, a sense of excitement crackled through the air. In the audience, conversation fell to a hush, a few sharp whispers weaving through the darkness. Across the auditorium, a shrill, uniform cheer rippled back through the aisles, some students raising their arms as if ready to dance. When Maestro Tom Duffy made his way out onto the stage, a listener could have mistaken the space for a stop on the Eras Tour.

Back in row O, Rhayn sat back and studied each movement on the stage, a ballet of tuning instruments and rustling sheet music. On dozens of music stands, Bizet’s “Los Toreadors” waited expectantly for a cue. Before it came, Stephan Tieszen stood with his violin, and turned toward Olav van Hezewijk for an A. Across the auditorium, Rhayn took mental notes, ready to bring what she had learned back to the school band.

“It feels nice,” she had said just moments before the concert started, adding that it was her first NHSO performance. As the audience stilled, she and Kelly watched as Duffy raised his arms—"my job is to tell the orchestra how fast they’re supposed to play,” he noted—and traveled instantly back in time, conjuring the warm winds of southern Spain. Woodwinds trilled their entrance. Strings entered at a clip and horns bellowed below. On a screen over the musicians, a bull pawed the earth, hooves sending up clouds of dust.

In the audience, a murmur of approval rippled through the dark rows, growing louder as the projection shifted, and a flamenco dancer moved in slow-motion, his chest glowing beneath an unbuttoned shirt. Baton gliding through the air, Duffy half-bounced in place, leaning in just so as strings slowed, then resumed their quick march forward. When a smattering of applause came early from somewhere left of the stage, he held up a single finger as if to say just wait for it. When the end came, the room erupted in sound.

They were just getting started, Duffy said from the podium. He jumped from 1875 to 2012, when a young Jessie Montgomery first introduced her composition “Starburst” to the world. The piece, commissioned by the Sphinx Virtuosi just over a decade ago, places ebullient, erupting strings beside sections that slow and sweeten the piece, sewing a sort of short, thrilling sonic tapestry.

“Imagine a thousand suns exploding all at once in a galaxy,” Duffy said, and that was all it took for students to snap back to attention. Above his head, a star began its journey through space. As if playing a soundtrack to its journey, musicians launched into the work, the sound spilling from the stage and drifting towards the ceiling.

Close to the back of the auditorium, Rhayn and Kelly made sure not to miss a moment, taking mental notes. As young Fair Haveners, the two play clarinet in the school band. Outside of school, both are students at Music Haven, where they study violin with Patrick Doane. In a room where silence itself felt miraculous and delicate, the two held onto each note.

“It made me imagine the worlds outside of ours,” Rhayn said in a conversation after the concert, already interested in learning more about Montgomery. “How beautiful they can be.”

“It made me feel like I was experiencing my favorite instruments again for the first time,” Kelly said.

That sense of revelation flowed through Dvořák’s “Serenade for Wind Instruments,” a projection dancing above the orchestra as the piece unfolded. It gained speed as musicians opened Dukas’ “Fanfare” from La Péri, horns blaring. It tittered and thrilled with Bernstein’s “Mambo,” a video from West Side Story flickering in the dark auditorium as students joined in on the hook. It bloomed into color as Damali Willingham joined musicians for Peck’s “The Thrill of the Orchestra,” and a pair of arms rose and danced in place somewhere around row H.

Martinez with band students from Fair Haven School.

But nowhere was it clearer than during Harberg’s “Prayer,” written in 2011 as a prayer for her mother, who was sick at the time. As students came down from a raucous “Mambo,” Duffy described the importance of listening closely to the piece, in which harp starts a gentle dialogue with the strings and orchestra. As the piece deepens, there is something sublime that weaves each section together, transforming the stage into a house of worship. While it is entirely Harberg’s own, a listener can close their eyes and hear the soft footfalls of “Ave Maria” folded into the work.

“Do you hope for things?” Duffy asked as a chorus of agreement rose up from the audience. “Does anybody hope for a world where we don’t fight each other? Does anybody hope for a world where we can be accepted, just as we are? Does anybody hope for a world where we can preserve our natural resources?”

In row O, Rhayn was thinking about a world without conflict and a friend who was sick. Beside her, Kelly was too. “I thought about if we could all be kind to each other,” she said afterwards.

“It helped me learn how to improve and enjoy what I’m doing,” Rhayn added.

That’s the hope, said NHSO Chief Executive Officer Elaine Carroll. While the concerts have continued largely uninterrupted since the 1930s, they’ve taken on a new kind of significance amidst the rise of tech platforms like Instagram and TikTok. In the past two years, both NHPS teachers and NHSO staff have found that the addition of projections and video help keep students engaged.

Following the performance, Carroll likened the experience to watching a professional baseball game, or listening to music through earbuds. It’s possible to follow along and enjoy the game—or the music—on a television screen or iPhone, but there’s no substitute for seeing it in person. “What you do in a live audience is so different.”

“This is a great experience for our kids,” added Ellen Maust, NHPS supervisor of performing and visual arts. She pointed to the significance of having concerts designed for young people, many of whom have not attended the symphony before, and may not be quite as buttoned-up as some of the symphony's decorum-conscious silver-haired patrons “When you’re at a live concert, it’s community.”