Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Film | High School in the Community | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | Public Health | History | Arts & Anti-racism

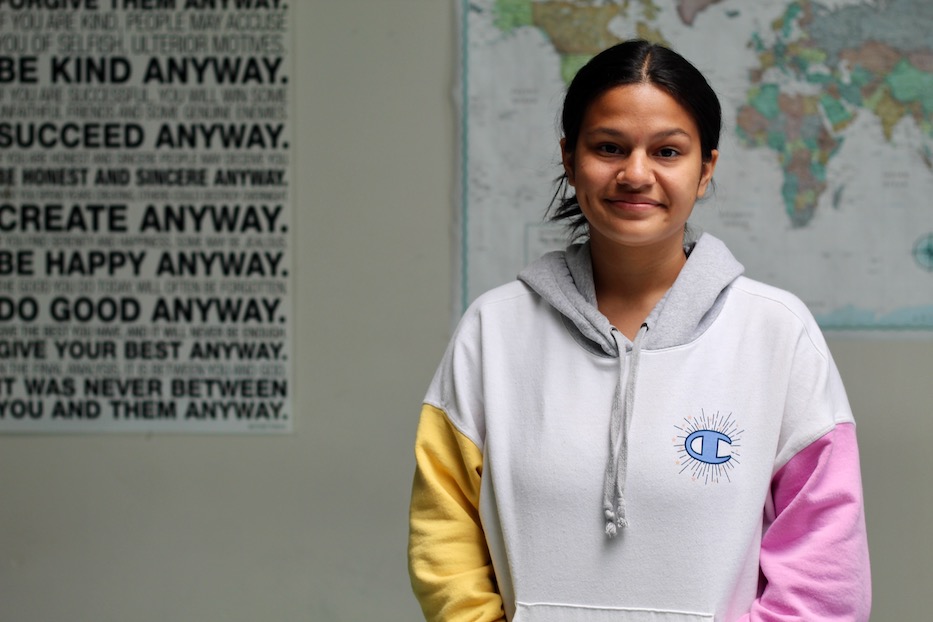

High School in the Community (HSC) freshman Jonaily Colón, who is headed to National History Day finals in Washington, D.C. this month. Lucy Gellman Photo. The image below of Colón with U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro is courtesy HSC.

The film begins with grainy, out-of-focus text and a somber voiceover, music building slowly beneath it. Off screen, a narrator recalls the moment he was stripped of his clothes and thrown half-naked into a cell. On screen, the image shifts to archival footage, and a pair of gloved hands are bearing down on a woman's forehead, a gag fixed across her mouth.

In an instant, a viewer wonders: When will this end?

The work—which blows a chapter of New Haven and American history wide open—is "Frontiers In 'Mental Hygiene:’ How Clifford W. Beers Shifted Attitudes Towards Mental Illness," a short documentary and National History Day triumph from High School in the Community (HSC) freshman Jonaily Colón.

This spring, Colón placed in both regional and state History Day competitions with the film, which explores the history and legacy of Clifford W. Beers on and well beyond New Haven. She will now travel to the national competition in Washington, D.C. from June 11 through the 15th. Peers, teachers and members of the HSC community covered the cost of that travel through a GoFundMe in under a week.

"Definitely with this project, I learned more about the past," she said in an interview Wednesday at HSC, sitting quietly in a history classroom as a cacophonous lunch hour unfolded in the cafeteria below. "I learned more about how people were treated. Especially Clifford W. Beers. He went through it all and still was able to keep a piece of his mind, so he could make such an impact on the world."

Colón's work on the film began back in September, when she stepped into a world history class with HSC teacher Danny Roque, and remembered what it felt like to be enthralled by and curious about the past. During her last two years of middle school, Colón didn’t have a reliable history teacher, and a string of substitutes left her lessons feeling incomplete.

Enter Roque, who has been teaching at HSC for 13 years and folds National History Day into his curricula. While students of all grades are invited to participate, he works primarily with freshmen. When he mentioned it to his classes—followed by a History Day project kickoff at the New Haven Museum—Colón was hooked.

From the outset, she said, she knew she wanted to focus on mental health. The topic is personal to her: she's seen depression, anxiety, and other mental health crises arise within her own family, and often felt like there's a cone of silence around discussing it.

"People say, 'Oh, you go to therapy, it's not going to be good for you, it's not gonna help you, you're spending money for nothing,'" she said. She believed that if she could paint a more complete picture of mental illness and its history, it would help break that stigma.

But originally, she wasn't sure what to study, she said. Mental health as a topic was wide and sprawling, with centuries of history to choose from. It was Roque and Khalil Quotap, director of education at the New Haven Museum, who encouraged her to find a New Haven angle for the project.

Her research led her to Beers, whose autobiography included his own experience with mental health and involuntary hospitalization, and a collaboration with psychiatrist Adolf Meyer that later became a revelation. When it was published in 1908, the book flew off shelves.

"His story nearly never saw daylight, as he was often refused paper to journal," Colón reads in the film. "Instead, he would write down his thoughts on pieces of toilet paper. The few times he was able to secure paper, he wrote lengthy lists of grievances and had to sneak his letter in the mail."

The more she learned, the more the history spoke to her. Beers was born in New Haven in 1876, one of four children who all ultimately suffered from mental illness. Even as a child, he worried that he would become mentally unwell, because he had seen an older brother suffer from and ultimately succumb to epilepsy.

During his years as a student at James Hillhouse High School, Beers began to notice "intrusive thoughts that ranged from physical abuse to suicide," Colón narrates in the film. By the time he graduated from Yale University in 1897, he was severely depressed. The end of the 19th century marked his first recorded psychotic episode: he attempted suicide by jumping out of a third-story window during dinner at home with his family. While he survived, his injuries landed him in a hospital, and then in a psychiatric institution.

As Colón continued to do research, she learned that Beers had himself been institutionalized three times at the beginning of the twentieth century, first at Stamford Hall, and then the Hartford Retreat, and the Connecticut State Hospital at Middletown. With archives at the New Haven Museum, she was able to pull historic images from those places, which she later folded into the film.

As Colón continued to do research, she learned that Beers had himself been institutionalized three times at the beginning of the twentieth century, first at Stamford Hall, and then the Hartford Retreat, and the Connecticut State Hospital at Middletown. With archives at the New Haven Museum, she was able to pull historic images from those places, which she later folded into the film.

From his autobiography, she also learned that Beers—and, it's likely, thousands of other Americans also put in these institutions—was tortured and restrained with instruments including muffs, sheets, shock therapy, and sedatives that would leave a patient unconscious for hours. The food offered, meanwhile, was hardly food at all. “It was disgusting,” Colón said, with such emphasis that her bagged lunch suddenly seemed like a gourmet meal.

Colón was horrified. And she was simultaneously inspired by Beers, who wrote publicly about his own experience with mental illness when no one else had broken that silence.

"The past, how everything used to be treated, I just can't put into words how brutal it was back then," she said. "Just the way people were treated back then in mental institutions was just horrible. They weren't given no human rights whatsoever. They were literally just put there for nothing, because they weren't getting the help they needed. Nothing."

She learned that after the publication of his autobiography in 1908, Beers embarked on a nationwide campaign to reform mental healthcare, which he referred to as “mental hygiene.” As an advocate (and with considerable financial support from philanthropist Henry Phipps), Beers compelled state legislatures to reconsider their laws, many writing new pieces of legislation.

In 1930, he brought together the first meeting of the National Committee for Mental Hygiene—the same group that he had founded in 1909. The group’s impact, little did he know then, would survive him for the next century.

In 1950, the National Committee for Mental Hygiene changed its name to Mental Health America, which is now a robust and still-active organization today. That shift came 11 years after Beers' own depression returned, and seven after he died of a brain tumor in 1943.

Colón chose documentary filmmaking—a medium with which she was completely unfamiliar—because it seemed like the best way to tell a story, she said. It meant that she was teaching herself how to record, splice, and video edit as she was doing research into Beers' life and work.

Roque, who was particularly impressed with the film and the research that went into it, remembered how she would come in every Thursday to work dutifully on the project. He praised her dedication, which was clear from the beginning and has not waned since September.

At the regional New Haven competition at Southern Connecticut State University earlier this year, the film placed third in its category—enough to move on to the state competition. But Colón wasn't happy with the result, she said. She went back to the film with a panel of teachers, sourced their feedback, and did a deep edit with completely new audio. She had her brother, Christopher, do voice overs of Beers' original writing.

She concluded with a section with a New Haven Public Schools (NHPS) social worker speaking on the value of mental healthcare. It paid off: she received first place in the "Independent Documentary" category at the state competition, held earlier this month at Central Connecticut State University. When she launched a GoFundMe campaign to get to nationals, which she will attend with her older sister, it was funded in under a week.

"We know the demographics of Connecticut," said HSC Building Leader Cari Strand, who added that it feels big for an HSC freshman to carry this honor. "There are a lot of students with some pretty significant advantages. You hear a lot about urban schools, and I think this shows that the work being done here is first-rate, and that our students are first-rate"

The process has reinvigorated her relationship with history, Colón said. It has also made her proud to represent HSC, New Haven, and Connecticut on a national stage. When Colón went to regionals and states, she was up against peers from whiter, wealthier school districts, including independent schools. She won because she had put the work in.

She knows that as she goes to the national competition, she's telling other young history nerds—particularly young women and people of color—from New Haven that they can do the same thing. She said she also feels more open talking about mental health than she ever has. In addition to a school psychologist and social worker, HSC has a representative from the ALIVE program, an initiative of the Foundation for Arts and Trauma, in the school every day of the week.

"The past is very interesting, because it's so different from now," she said. "And at the same time, to this day, people still think that they're better than people who do deal with [mental health] issues. There's definitely that separation. So I hope to really see that change."

Roque, who has been cheering her on from the moment the project started, said he is incredibly proud. At the regional competition earlier this year, he remembered looking around and realizing how white the event was. There was a clear resource gap, and Colón bridged it with her sheer resolve to succeed.

"We were the only school that had students of our population," he said. He called it a testament to both Colón work—she is an A student in almost all of her classes—and to the tight-knit school that she was funded in under a week.

At the statewide History Day competition, special awards also went to HSC students Isabella Rivera, Nicole Tubac, Marbella Escobar Gonzalez, and Yeilienys Ojeda. In all, New Haven sent 14 students to states.

Clifford Beers Community Care Center, meanwhile, has also taken note of Colón’s work. On June 8, she and Roque will be guests at the clinic’s annual Builders of Hope breakfast at the Woodwinds in Branford, where the documentary will be playing on loop in the venue’s lobby.

In a phone call Friday morning, Clifford Beers Executive Director Melanie Rossacci praised the documentary, adding that she had been amazed to learn that Colón was a freshman. After watching it for the first time last month, she sent it to the organization’s board members in honor of Mental Health Awareness Month.

“It really talked about mental health in the way we like to talk about it at Clifford Beers,” she said. “The work that we do is rooted in advocacy of mental health patients.”

She added that she would like to connect with more high school students in the future, as a way to expose them to the fields of mental health and social work at an earlier age.