Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | Education | LULAC Head Start

Executive Director Mikyle Byrd-Vaughn with Zael. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Executive Director Mikyle Byrd-Vaughn with Zael. Lucy Gellman Photos.

The sound of drumming rolled down the hallway, so gentle that at first it could have been mistaken for footsteps. It grew louder, quickening as pairs of tiny hands joined in. Soon, it was a danceable beat, bouncing as it came up through the floor. High-pitched peals of laughter rang out, and sounded like musical accompaniment. It was just past 10 a.m., and LULAC Head Start had its first orchestra of the day.

Welcome to LULAC Head Start's Future Leaders Center, 15,000 new square feet of classroom and work space at 106 Haven St. in Fair Haven, in the home of a former Consiglio’s warehouse for dry goods. After months of renovations and the buildout of a second story, the building opened to families on January 24. It joins the preschool’s other home at 250 Cedar St. and expands the work the organization was doing at its Mill River Center, at 375 James St.

It currently serves 100 children between the ages of two months and five years old, with capacity for another 20 once the second floor is completely finished. Contractors are also in the process of working on a large second-floor gymnasium, where dance classes are set to begin later this year. Across its sites, said Executive Director Mikyle Byrd-Vaughn, LULAC employs over 101 educators and staff, at a time when childcare is very much in crisis in New Haven, across the state, and nationwide.

"The teachers are smiling," said Byrd-Vaughn, who stepped into the role in 2016. "Everyone's happy. When I'm doing rounds [to the classrooms], the children are engaged. There’s so much learning happening."

Ayanni (in the pink) chooses a toy as she does self-directed learning.

It has been a labor of love. Work on the new center began over a year ago, after Byrd-Vaughn secured federal funding that could grow the organization's footprint in Fair Haven. Most of LULAC’s families are walking families: they live in the neighborhood, and drop their kids off on foot during the week. That meant that staying in Fair Haven was important to the organization.

From its original 7,500 square feet, LULAC doubled the building’s space with a second floor, where the gymnasium and a few administrative offices are still under construction. Working with architect Alexandra Sloan, Byrd-Vaughn designed classrooms with shared kitchen and bathroom spaces, smartboards, and lights that could dim in one part of the classroom and stay on in another (in case, for instance, some kids want to nap and others want to read or play).

The name—LULAC’s Future Leaders Center—came out of a staff-wide contest. Byrd-Vaughn praised educator Kashonda Lawrence for coming up with the winning title. “It was just beautiful,” she said. For her, it encapsulates “the values and spirit” of the organization, from its youngest learners to former students who return with their own kids and grandkids years later.

A first-floor classroom. Kids at LULAC start at two months and go up to five years. The idea behind the space is that those first five years of life—and before kindergarten—are critical to a child's development.

For both her and the staff who work there, it's also part of expanding LULAC’s mission to provide early childhood education and care focused on the whole child. First founded in 1983, the program gained accreditation from the National Association for the Education of Young Children in 1994, and became a recipient of federal Head Start funding for the first time in 2014.

The designation means that it qualifies for significant federal support, allowing it to offer free and highly subsidized options for families who might otherwise find it prohibitive.

In recent years, that has included an integrated approach to education both in the classroom and beyond it. LULAC tracks students’ developmental, dental, vision, nutritional and even housing needs. It’s especially crucial as students return from Covid-19, Byrd-Vaughn said.

“When kids came back, they didn’t know how to sit, they didn’t know how to share,” she said. “We saw huge social and behavioral changes.”

It’s an approach that is working, she added. Last year, 80 percent of students met their expected developmental milestones. Babies and young kids with diagnosed needs—like learning differences, or developmental delays—get help from a support specialist on site. Currently, Byrd-Vaughn said, that makes up about 30 percent of their young population.

Jennifer Rivas and Nataliya.

On a tour of the building on a recent Friday, that whole-student approach was in full swing—and sometimes at full volume. As she walked into one first-floor classroom, Byrd-Vaughn watched a delicate ballet of play, reading, and fine motor skills unfold in real time. On a polka-dotted carpet, teachers Jennifer Rivas and Chineer Thompson scooted from one student to the other, fielding requests as they came.

At one end of the carpet, Rivas greeted two-year-old Nataliya (LULAC asked that only first names be used), watching as she held up a board book, and then opened it gently to the colorful drawings inside. A baby doll sat quietly in front of them as she pointed to the red and yellow houses. Babbling and chatter rose in both English and Spanish: LULAC makes sure that there is at least one bilingual educator in each classroom.

It was hard to believe the classroom had only been open for a few months: it seemed lived in and well-loved, like a second home to the little humans inside. On a kid-sized bookshelf, Black and Brown plastic figurines grinned politely, as if they were saying hello. Taking her time to look over them, preschooler Ayanni lifted up a squishy, orange cat, then put it down for a book.

“It’s self-directed learning,” Byrd-Vaughn said as she looked around. At LULAC, she said, one of the biggest misconceptions she’s faced is that “child care is really babysitting.” Instead, the approach is dedicated to helping little ones meet their developmental milestones before kindergarten. The research is on her side: studies show that the first five years of a child’s life are most critical to their development.

Teacher Garrett McMann with a three- to five-year-old class.

Byrd-Vaughn kept her eye on Zael, a quiet toddler who had been watching everything from the corner. In one fell swoop, she picked him up, and began to have a conversation in both words (hers) and delighted squeals and babbles (his). Sometimes, she said, she or fellow educators will give a student a little extra socialization time. Resting him gently on her hip, she headed toward the second floor. Even from the staircase, the occasional sound of laughter bubbled out into the hallway as classroom doors opened and then closed again.

Upstairs, teacher Garrett McMann was starting the day with creative movement and dance for his three- to five-year-olds. A few students stood in front of a video screen, jumping in time with music; others colored, assembled building blocks, and played house. From a table in the corner, a three-year-old offered Byrd-Vaughn a cup of pretend coffee. She beamed, putting aside a green smoothie as she accepted it. Zael eyed it warily, as if there were steaming liquid sloshing over the top.

“Is it strong?” Byrd-Vaughn asked. “That’s how I like it.”

“Yes!” the girl exclaimed. Byrd-Vaughn lifted it to her lips, pretending to take a sip even as an inch of space remained in between.

“Whew! It is strong!” she replied.

Family Services Coordinator Janic Maysonet, who is a LULAC alum.

Nearby, Family Services Coordinator Janic Maysonet smiled at the exchange as he knelt down to study drawings from students Angel and Emiliano. Born and raised in Fair Haven, Maysonet is himself a LULAC alum, and said that the organization has taught him to be both a stronger educator and child and parent advocate, and a better dad.

As she walked through the building, Byrd-Vaughn pointed out new office space, staff members working away inside. In addition to its regular programming five days a week, LULAC coordinates quarterly dental and vision screenings for students. In late February, photos of kids brushing their teeth filled social media, foam and pearly whites flashing as they smiled for the camera.

Edita Tamulionyte, health promotion specialist at LULAC, said that it’s part of the preschool’s belief that early childhood education goes far beyond the classroom. When she’s teaching kids about dental hygiene, for instance, she tries to engage their parents in lesson planning, to make sure that the learning continues at home. Two “specials” teachers—a music educator and science learning team—also come in once a week and once a month respectively.

LULAC is still working within a childcare crisis, Byrd-Vaughn said. Even with the new space, there are still close to 150 children on LULAC’s waitlist, the majority of whom are infants and toddlers. LULAC is now open 48 of the 52 weeks in the year, because staff members “need to replenish and restore too,” she said.

In addition to a $7 million operating budget, she’s raising grants for professional development and staff activities. After completing a compensation study, LULAC is working to increase salaries to a competitive level for early childhood learning professionals.

“We’re doing our best to keep our teachers,” she said.

A Head Start To Housing

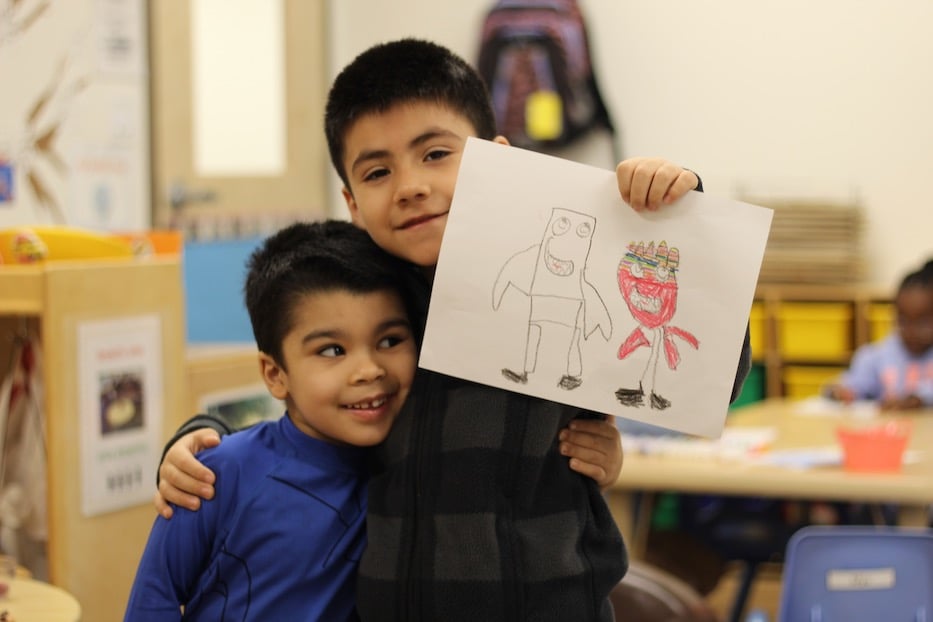

Angel and Emiliano.

Some of that evolution also happens quietly, as staff help families sift through small mountains of paperwork. Last year, LULAC became one of the first statewide partners in Connecticut's "Headstart on Housing" pilot, which connects LULAC to the Department of Housing and works together to help vulnerable families. The program, which is less than a full year old, provides rental vouchers to families facing housing insecurity and homelessness with young kids.

Meghan Gonzalez is one of those parents. In a phone call Wednesday, she credited Maysonet with helping her get her kids into preschool, and moving her family into an apartment, and out of a five-year cycle of housing insecurity.

She remembered becoming homeless five years ago, when her husband lost his job. At the time, Gonzalez was coming back from maternity leave, and was also let go. Unable to make rent, they and their children bounced between motel rooms and the homes of family members.

It was a nightmare, Gonzalez said. Staying with family members wasn’t always safe. Neither was the motel, where she saw roaches and bedbugs on a daily basis. Her four children, who now range from six years to six weeks old, didn’t know what it was like to stay in a single, permanent place for more than a few days. She lived in fear that the family would be separated, she said.

Then last year, she connected with Maysonet through her husband’s aunt, who had for years worked at LULAC. He took on the family’s case with what felt like everything he had, she remembered. If she called, he picked up the phone every time. He helped her through pages and pages of paperwork. On May 16 last year, the family moved into an apartment that was theirs.

“LULAC got us off the street,” she said. “We were losing hope. I would call Janic, and he would always pick up. He was on top of everything. … I owe him my life.”

There’s still a very present trauma that comes with being housing insecure, she said. When the family moved into their apartment last May, her kids began to pack up their belongings after a day. “They didn’t know what home was,” she recalled. She had to reassure them that they could stay.

“A three-year-old should not know what it is like to be homeless,” she said.

She added that she has been delighted by LULAC as a parent. After enrolling two children in the program, she didn’t know what to expect. Originally, she said, she was wary of daycare providers. Then LULAC was in touch multiple times a day, with progress reports and sent photo updates. She felt like she was being kept in the loop.

“I speak to people about it all the time,” she said. “People who go through situations [like what] we went through. LULAC got us through everything.”