Halfway through their reading, poet Whitney Graham faltered. They had been weaving a story of blistering injustice, from Palestine to Sudan, but they were unable to remember their next line. As if on cue, audience members started snapping their fingers, clapping, and cheering, encouraging Graham to go on. With a shaky laugh, they got out their phone and completed their poem to thunderous applause.

Halfway through their reading, poet Whitney Graham faltered. They had been weaving a story of blistering injustice, from Palestine to Sudan, but they were unable to remember their next line. As if on cue, audience members started snapping their fingers, clapping, and cheering, encouraging Graham to go on. With a shaky laugh, they got out their phone and completed their poem to thunderous applause.

Monday, the Yale Peabody Museum, in collaboration with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection and the New Haven Museum, hosted its 29th annual commemoration of Dr. Martin Luther King, including the now-beloved open mic and Z Experience Poetry Slam. A full day of free programming took place across both museums, as well as the O.C. Marsh Lecture Hall, celebrating Dr. King’s legacy as an orator and civil rights pioneer.

“The open mic is where the real heart of poetry is,” said New Haven Poet Laureate Sharmont Influence-Little, a longtime participant and first-time host of the Community Poetry Open Mic. He recalled the first open mic he ever attended at the Ives Main Branch of the public library. It was the most supportive place for his craft that he’d experienced at the time. “You don't have to worry about putting on a show. You can come up there. You can read. You don't have to be perfect; a perfect performance, or a perfect cadence. It can just be you and the page and the release.”

It is exactly Dr. King’s raw oratory power that the Z Experience Invitational Poetry Slam, named after cultural icon and program founder Zanette Lewis, sought to honor Monday. Nearly 200 New Haven residents, students, and artists braved fresh-fallen snow and filed into the cavernous O.C. Marsh Lecture Hall to watch the slam, which featured four poetry slam teams from across New England.

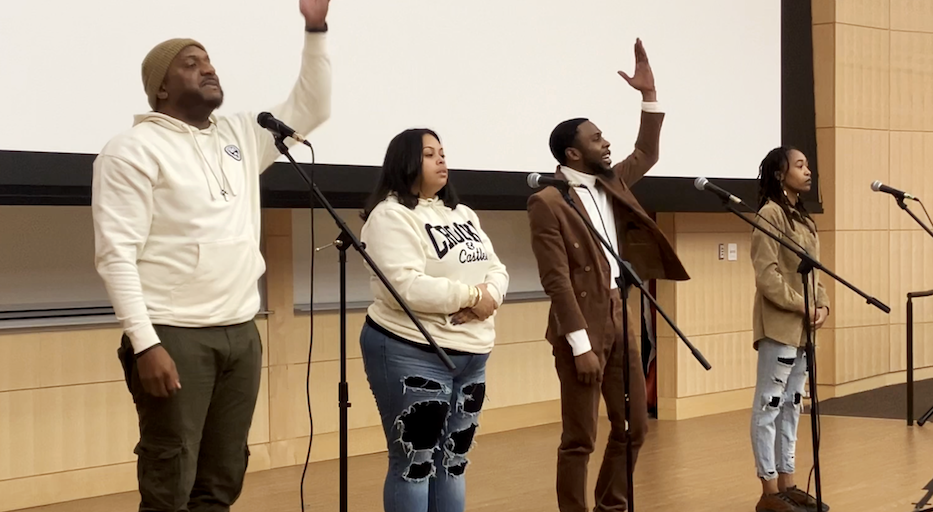

Finger-snaps filled the air as teams performed on themes of gentrification, Black masculinity, and cultural alienation. After multiple rounds and gruelling judging, home team Verbal Slap took home the trophy, with Massachusetts' Team News finishing close behind.

But it was the preceding hour, the Community Poetry Open Mic, that unexpectedly stole audience members' hearts. “The slam is definitely a show,” said Influence, who had the open mic hosting baton passed to him by poet Croilot Semexant, who in turn hosted the invitational slam. “It's rehearsed. You practice your poems over and over again to make sure you have them memorized, and you practice your cadence and you practice your movement. With an open mic, it's just raw.”

One of Dr. King’s most famous speeches at Holt Street Baptist Church, just days after Rosa Parks’ arrest, was largely extemporaneous. He composed it right before the meeting. And indeed, some poets read poems they had crafted only the night before, using their performance to process current events. They came up to the stage with notebooks, pages, and their phones.

Jasmine Eaton, a Bridgeport-based poet who performs under the stage name jazz-e, recited a poem wondering aloud whether the hip-hop industry was holding powerful and abusive artists like P-Diddy accountable. “Are we hating hard enough?” she asked the crowd, reading from bright pink pages. Every few stanzas she would discard a sheet, letting it flutter to the ground. “Does the rhythm rob us from seeing?”

Poet Lyrical Faith dissected global anti-Blackness in her poem about Meghan Markle and Kamala Harris. Her line about Donald Trump’s 2024 election win, “America will do anything to prove she can keep her man,” elicited whoops from the crowd.

“Fire, fire, fire,” said Influence, coming to the stage after her reading. He turned to Ngoma Hill, a legendary New York-based performance poet (and longtime Z Experience Poetry Slam host) who was sitting in the audience, and observed: “Correct me if I’m wrong, Ngoma, but it was the open mics that sounded the warning sirens and educated people, before slams.”

Verbal Slap performs during the Z Experience Poetry Slam. Photos courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum.

Little later elaborated on the format’s unique history. “Open mic spaces are where poets like Gil Scott-Heron, The Last Poets, and Gwendolyn Brooks [emerged]. That's where the people of our neighborhoods got our information. About what was happening in society, what was happening in government. About who we should be looking to vote for, about what problems were going on. It was a continuation from our heritage of what's called the griot, which is the storyteller. We would meet in basements. We would meet in all kinds of places that no one knew about, just our community. And we would do poetry. African drumming. Stuff like that.”

Influence is presently working on a poem about Dr. King’s speech to the sanitation workers of Memphis in 1968. Reflecting on the day’s celebrations, the concurrent presidential inauguration felt like an inescapable comparison.

“As far as Dr. King's dream goes, I think we're kind of living a nightmare,” he said. “The great thing about the nightmare, though, we always seem to wake up and survive despite whatever America decides to do. We’re continuing to go through the valleys, after Martin saw the mountaintop. We're still traveling those valleys. We haven't gotten to the Promised Land yet.”

Monday felt celebratory for another reason: This is the Peabody's first on-site MLK Celebration since its reopening in March of last year. The museum has returned with an eye towards forging deeper relationships with New Haven. Its partners for this event included the New Haven Free Public Library, Students for Educational Justice, New Haven Public Schools, and the Dixwell Community Q House.

“The renovation gave us an opportunity to think in different ways about knowledge, and whose knowledge is valued,” said Andrea Motto, assistant director of public education and outreach at the Peabody. A key focus has been to build longstanding partnerships with Black-founded community organizations and spotlight their social justice work throughout the year.

Maya Gant, an education coordinator brought on to help with New Haven and youth engagement, added that “Having [the relationship between Peabody and New Haven] be reciprocal instead of feeling transactional has been a really big step, I think. You come to us, we come to you.”

Gant interviewed her grandfather, along with other senior members of the Q House, for a short video testimonial about those who had worked with MLK on voter rights and other civil rights issues during the 1960s. The video played in the multimedia museum exhibits during the day.

“Within the Black community, oral storytelling has been something that is a big founding influence. I mean, I remember stories from my childhood. And one of the ideas that I had was just that, like, we need to get these stories on film,” Gant said. “My grandfather's 91 years old. Dr. King would have turned 96 this year. The generations of people who planted the seeds for the tree that we're all sitting under right now are getting old, and we don't want these stories to die with them.”