Culture & Community | Arts & Culture | Visual Arts | Quinnipiac University | Literacy | North Haven | Arts & Anti-racism | Comics | Kulturally Lit

Shenkarr Davis and Taekyung Bennett. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Taekyung Bennett—or maybe it was Miles Morales—stood methodically in front of four panels, inspecting his handiwork. In the first, a superhero charged forward, his hands balled into huge, heavy firsts inside bright red gloves. On the panel beside him, a woman brought one hand to her mouth, her eyes wide with fear. One panel over, another superhero entered the fray, and flipped the first. She floated over the ground, a blur of green and black.

Taekyung ran his tongue up against the top of his mouth and against his teeth, creating a steady click-clack that rose and fell softly at the front of the room. He took a deep breath and began to tell the story of what was happening. Around him, the whole room hung on to every word.

The power of history, narrative, and representation rose to epic proportions Saturday, as Kulturally Lit’s second annual DiasporaCon rolled into Quinnipiac University’s North Campus for a full day of panels, vendor visits, cosplay appearances and what some participants described as serious Blerding Out. Supported by Quinnipiac University, it centered multiple types of literacy, with a focus on the past, present and future of comics and the role of Black and Afro-Latino creatives in them.

Kulturally Lit Founder IfeMichelle Gardin. Lucy Gellman Photos.

“When we had [the inaugural] Lit Fest, and we had the comic book panel, I started learning from [Professor] Bill Foster and his colleagues, I was like ‘Oh shoot, we need our own thing,’” said Kulturally Lit Founder IfeMichelle Gardin, who runs the organization with Shamain McAllister, Juanita Austin, and Zanaiya Léon. “Finding out about all the Cons that are happening and Black-centered, people of color centered—it was like, ‘Wow, let’s do this.’”

“A lot of times, organizations have good ideas, and limited access to spaces—so I think being able to do things like this, on a college campus, is beneficial in a number of ways,” added Dr. Don Sawyer, vice president for equity, inclusion, and leadership and an associate professor of sociology at Quinnipac. “It shows a community-university partnership, but also I think it’s important, when the young people are here on a college campus, they can come in here and see that this is not above them.”

From sessions on branding and storyboard creation to a history-soaked afternoon keynote, the event reminded attendees that there have always been Black and Afro-Latino heroes here on earth, fighting against a world turned on its head by supervillains (and white supremacy, but call it Venom). As artist Raheem Nelson walked attendees through his style of graphic recording upstairs, a low hum of conversation rose on the first floor, where comic book writers, illustrators, and enthusiasts had set out vendor tables.

Ramon Campos and Oswaldo “Ozzie” Nevers. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Just to the right of the entrance, cousins Ramon Campos and Oswaldo “Ozzie” Nevers introduced High Five Studios, a still-young venture based in Queens that has birthed the new series Black Book. In the book, five friends discover that their artistic skills are their superpower. Together, they must use their creativity to fend off villains, excel in art school, and decipher ancient languages. No big, right?

“It’s asking like, what would have happened if the Renaissance had not died out?” Campos said Saturday, holding up a copy of the book covered in bronze-tinted film. It caught and glowed in the light.

For Campos, who is a toy designer with Universal Studios, Black Book also marks a full-circle moment. Born in Venezuela and raised in Queens, Campos grew up watching and reading comics, but rarely saw characters who looked like him in their pages. It was the 1980s, and Sailor Moon, the Ninja Turtles, X-Men, GI Joe and Teen Titans all became part of his orbit, he said. As he entered the workforce—first as a student at the Fashion Institute of Technology, and then as a toy designer for Hasbro and Universal—he still felt like something was missing.

Artist Shishawna Warren (at right) and her mom, Jacqueline Warren. Shishawna runs a crochet business that helps her with anxiety, Saturday, she was selling a number of crocheted toys and hats. The money helps her pay for college. Lucy Gellman Photos.

It led him to found High Five Studios, a creative hub based in Queens that is the publisher of Black Book. After two years of “spinning wheels” and storyboarding, the first issue of Black Book came out last year; another is forthcoming. On Saturday, Campos described it as a way to give kids in his neighborhood—and across the globe—access to the kinds of characters he dreamed of seeing as a kid.

Those include his one-year-old daughter Valentina, who he described as “my highest level of inspiration.” It’s what keeps him going when he’s balancing illustration and co-writing with Nevers with a full-time job. As he spoke, illustrator Ray Felix seemed to take note nearby, and lifted up a sketch of his character “Black Power” to show a new attendee.

“I wanted to build something for her,” Campos said. “The company is trying to create a hub for creatives to come together and support each other, to tell stories from a different perspective.”

Reva and Reginald (Reggie) Augustine. Augustine hand-painted the shirts that they are wearing. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Across the room, Connecticut-based writers and illustrators Reggie Augustine and Tangular Irby both dipped into history with their work, which spans New Haven’s past and present to the rich Black quilting traditions of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. At one table, Augustine and his wife, Reva, invited attendees to learn about the still-nascent company Elm City Comics, a lifelong dream of Augustine’s that blossomed during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Born and raised in New Haven, Augustine has been writing and illustrating for years, empowering the next generation of artists as he leaves a graphic footprint on the city. By day, is a teacher at James Hillhouse High School, where he teaches cartooning and is starting an after-school art program. By night, he is the writer, illustrator, and publisher behind Elm City Comics.

In his books, of which he now has three issues released and four “drawn and inked,” New Haven is often the real-life backdrop for other-worldly storytelling. For instance, the characters in his Aphro Physt Vs. Protector Force series have their headquarters in Fair Haven, where an underwater entrance off River Street gets them into their building. When a psychic vampire comes to town, it makes its grand entrance through the Grove Street Cemetery, where the gates still read “The Dead Shall Be Raised” in a holdover from 1796.

There’s a certain, large and well-resourced “Hale University” in the center of town, where evil comes to play. He does research on how the city has evolved over time, from its oystering past on the Quinnipiac River to buildings that have been demolished.

And of course, he and Reva make the occasional appearance. She is his muse, he added: Reva asked him to make a comic book for her when the two got married. The rest is history.

Jennifer Heikkila Díaz and her children, Gabriela and Magdalena. Lucy Gellman Photos.

One table over, Irby unfolded a legacy that traveled, stitch by stitch, from Alabama to a university conference room in North Haven. In front of her, copies of the children’s books Pearl and Her Gee’s Bend Quilt and Charles and His Gee’s Bend Quilt laid alongside thick, well-loved art books with glossy photos of the quilts at Gee’s Bend. On each book, a young child held up a quilt, blocks of pink and orange color vibrant at the edges. Bands of blue turned into rays as they rotated around sun-yellow circles.

While she grew up in Bridgeport, Irby is a descendant of the legendary Gee’s Bend quilters, and has long wanted to share that history with a wider audience, she said. Before she was born, her parents headed north from Alabama, ultimately finding a home in Bridgeport. Her two grandmothers, Perlie Kennedy Pettway and Jensie Lee Irby, remained down South. While “I was blessed to know both of them,” Irby herself learned to quilt in Connecticut.

For years, Irby got used to hearing the history from her aunt Mary, to whom an afterward in the book is dedicated. Every time the two spoke, “I kept saying, ‘auntie, you need to be in a book!’” she remembered. Then in the summer of 2020, she watched organizers respond to the state-sanctioned murder of George Floyd. Something clicked. She realized she needed to tell her family’s story.

Ron Hill, who recently moved to New Haven from Philadelphia, with writer and illustrator Javon Stokes. Lucy Gellman Photos.

In the book, illustrated by India Sheana, Pearl (and in a different version, Charles) wants to make her own quilt in the style of Gee’s Bend quilters, from whom she comes. As she sits on the floor with her friends, the smell of Sunday dinner thick and low in the air, they start talking about quilting, and the designs that have made Gee’s Bend a national treasure and part of living history. She details a history of struggle, poverty and communal care that built the quilting tradition. Together, the friends begin to make a quilt.

“They had no formal education, no formal training—and look at the skill and artistry,” Irby said of her grandmothers, motioning to a glossy image of a quilt on the table. “Every family has a story, and I want to motivate them [young people] to share theirs.”

William Foster, who later gave the day’s keynote, listened as she spoke. “My grandmother gave me a quilt before I left for college,” he finally said. “Every night when I went away, I slept like a baby.”

Artist Javon Stokes, who grew up in Hartford and now lives in Windsor. Lucy Gellman Photos.

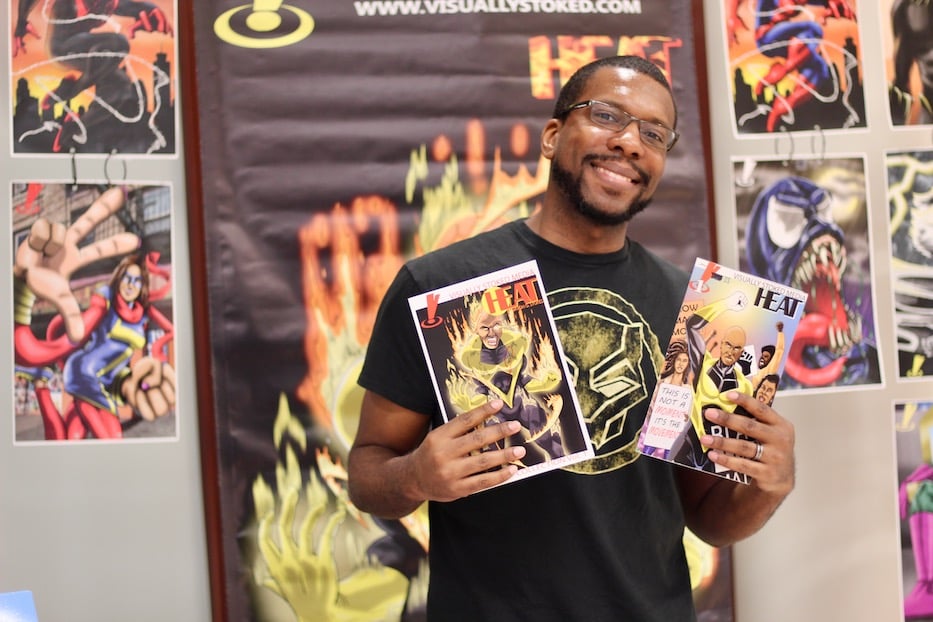

Across the room, Javon Stokes showed off issues of Heat, which comes out of his Windsor-based publisher Visually Stoked Media. Born in Hartford, “I don’t remember a time in my life when I wasn’t doing art,” he said.

That didn’t always mean he had good company. “It was lonely,” he said. At school, people made fun of Stokes for being a comic book nerd. He wasn’t deterred: he tried to buy and read every comic book he could get his hands on. The comics he gravitated towards—Captain America, X-Men, Spider-Man—didn’t always seem to have space for someone who looked like him.

“I was alone in the vast ocean,” he said. “That’s why I like the world now. It’s a lot less taboo [to like comics].”

Ray Felix, Robert J. Sodaro and Tom Sciacca at DiasporaCon. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Back at a table for Bronx Heroes, artist and founder Ray Felix showed off sketches of his character “Black Power,” who seemed to rise up from where he was inked on the page. Born and raised in the Bronx, Felix said that he is most inspired by his dreams. That’s part of how “Black Power,” inspired by the Black Power movement, was born.

“If the Black Power movement had launched, what would have happened?” he said. He added that his characters come from wanting to increase literacy around social justice movements. At home, Felix’s dad was a boxer, and taught his kids about Muhammad Ali. It led to Felix’s own education around the Black Panthers and role of Black organizers in the movement against the Vietnam war and the military industrial complex.

Now, he’s trying to pass that knowledge on through his visual art.

Just inches from his animated hands, fellow Bronx Heroes illustrator Tom Sciacca showed off copies of Trumpland, a comic book that staff members began to talk about, and then began to write when Donald Trump launched his campaign for president in 2015. As they put together a story with Trump as the evil supervillain, publishers in the U.S. wouldn’t touch it. A Canadian publisher ultimately picked it up.

“It rhymes!” Felix chimed in. “Some people even compared it to Hamilton!”

“You Tell Your Story, Your Way”

Shenkarr Davis. Lucy Gellman Photos.

That excitement flowed through the remainder of the afternoon, as presenters gathered in a university auditorium and upstairs conference room for several hours of panel discussions. Still nibbling their apples and cookies from lunch, attendees filed in to listen to Shenkarr Davis, an organizer of the East Coast Black Age of Comics Convention (ECBACC).

Davis, who is based in Philadelphia, had come to present “Storytelling That Advances Reading Skills,” or S.T.A.R.S. When he realized there were more adults than kids in the room, he scanned the space, flipping the lesson plan in his head.

He spotted Taekyung in the front row, rocking a Spider-Man suit as he sat beside his mom, the spoken word poet Lady Obsidian Rain. “Who is your favorite superhero?” he asked. When a mashup of Peter Parker and Miles Morales came back as the answer, he smiled and joked that he’d had a guess.

“What’s your favorite superpower?” Davis asked.

“He makes webs,” Taekyung said, moving his hands as if he was spinning a thick, translucent thread between them. “Spider sense!”

Davis spotted another pint-sized listener. “Who is your favorite superhero?”

Taekyung Bennett (or is it Miles Morales?) and his mom (dressed as a warrior) Lady Obsidian Rain. Lucy Gellman Photos.

“Wonder Woman!” a small voice piped up from several rows back. Davis pointed to Wonder Woman’s lesser-known fraternal twin sister, Nubia as a teaching moment. When Nubia appeared in 1973, she was the first Black women superhero to grace the pages of DC Comics. “She looks like you,” Davis added, without ever having to say the word “representation” aloud.

Emboldened, other attendees of all ages began to join in. “Rogue, Storm, and Phoenix!” ventured Lady Obsidian Rain from the front row. “Professor X!” said Mozel Daniels, who added that he was inspired by the hero’s role as an educator. Davis said that for him, he had always loved John Stewart’s Green Lantern, whose strength and resolve was based on will power.

“No one tells his story,” Davis said. He looked to canonical Black superheroes—Marvel’s Luke Cage and The Falcon—as both made out to be more flawed and more morally complicated than their white counterparts. John Stewart, for instance, was convicted of a crime he didn’t commit. Luke Cage “was a hero for hire.” None of them got the same, straight-up star treatment of a Captain America or a Clark Kent.

“Someone that’s not you is telling your story,” Davis said. He arranged four panels at the front of the room, inviting attendees to rearrange them into their own narrative. “Today, you’re gonna tell your story your way.”

Mozel Daniels. Lucy Gellman Photos.

After a pause, a few attendees stepped forward. Musician Finn Wiggins-Henry looked over the panels, then began to move them. “I saw a brother and sister, just like, play fighting,” Wiggins-Henry said as she continued experimenting with the sequence.

Others pushed themselves to imagine stories complete with whole scripts and voices for different characters. As she came to the front of the room, Shamain McAllister arranged them so that attendees saw a superhero charging forward, followed by a woman lifting her hand to her mouth, then a clear interception. McAllister explained that in her version, the first superhero had ingested something that was making him act crazy.

“My girl here is scared,” she said, pointing to the second panel. “And then—” she motioned to the next panel, where a new female superhero appeared for the first time. “She’s like ‘Beloved, come back into it.’ She had to flip him. Cause he was gonna wile out.”

As laughter bubbled up from the front rows, McAllister said she’s still one for a happy ending. After flying her friend to Mount Sinai, the female superhero figured out what was wrong. Her friend had been set up. “It was the feds,” she said, and the room broke into welcome, knowing laughter.

Yumy Odom, who is the founder and president of ECBACC. Lucy Gellman Photos.

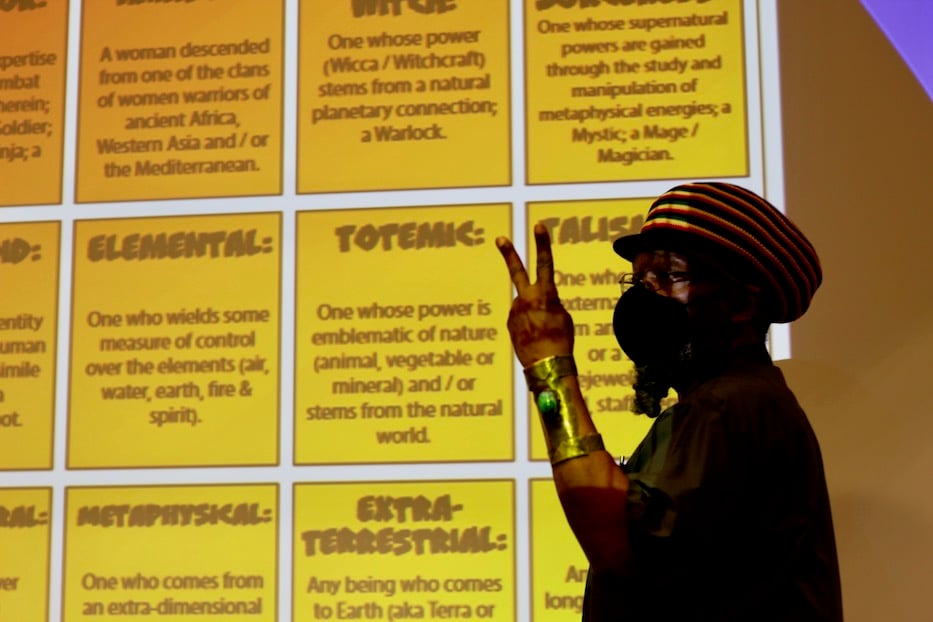

Other presenters kept that hands-on approach going, making the auditorium feel more like a living room or dinner table than a formal campus space. Yumy Odom, who is the founder and president of ECBACC, turned attendees into Black superheroes as he asked each what their superpower would be. He looked to history, reminding attendees that some age-old stories have their comic book equivalents. Moses of the New Testament, for instance, becomes Superman.

When he took the floor for storyboard creation, Augustine pulled up a comic book script and handed out thick sheets of paper and pencils. As he cracked jokes about his collection of some 50,000 comic books at home, the gentle whisper of pen and pencil on graphite filled the room. Then he got serious, explaining that scripts don’t always work for him.

“Because I’m doing everything on my own, it’s running in my head like a movie,” he said.

A few rows back, attendees Armani Gray, Wesley Frasier and Shawn Thigpen started in on their images, splitting their pages into neat storyboards. All three have known Augustine for decades: Gray was his student at Wexler-Grant Community School, and Frasier and Thigpen met him through siblings and fellow students. All said they are interested in comic books because of Augustine’s impact on them.

“You Can’t Find Out About American History And Leave Us Out”

Top: Professor William Foster. Bottom: Empress Jasmine and Onkey Cosplay. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Before the day was done, cosplayers and creatives also looked to the past, present, and future of what some panelists referred to as Black Nerds or “Blerds,” bridging time and space in a university auditorium. As they chatted, afternoon panelists jumped from potential mutant superpowers to the importance of affinity spaces to distancing themselves from Steve Urkel, "Blerd" nomenclature, and favorite cosplay characters.

“We typically make everything better because we are the originator of it,” said JuiceMan Cosplay, smiling a little at the smattering of snaps and applause that followed. “What it [Blerd] means to me personally is just to exist as a person and be Black and beautiful while doing it.”

“People assume that we want to cosplay Black characters,” chimed in Empress Jasmine. Not so, she continued: Black people are interested in cosplaying all characters, just as white people often cosplay Asian characters without a second thought. The only catch in the convention world is that white is assumed as the default.

Letif Belcher and JuiceMan Cosplay. Lucy Gellman Photos.

She pointed to an incident two years ago, when a white woman won a cosplay contest at Blerdcon, taking the honor away from the Black people who had gathered there to be in community with each other. Empress Jasmine was one of those people—and was part of the contest. She moved past it by recognizing what she got from cosplay in her own life.

“I feel like it brings you to everyone,” she said. She lives at multiple intersections, she added: she is African American, Jamaican and Chinese. “You’ll meet other people who can teach you about culture.”

Poet Letif Belcher, who runs the company Belcher Digital, said that he has spent years working to reconcile his Blackness and his nerdiness. He urged attendees to resist the pressure to assimilate or tone down his personality, particularly when it came from peers and colleagues.

“The older I got, the less I cared,” he said. “I literally fought to be who I am right now.”

Foster picked up that same narrative thread with his keynote. Taking attendees back, he remembered growing up in Philadelphia, where he collected 35-cent boxes of books at a consignment shop next door to his home. It sparked a love for comic books that followed him through multiple degrees and decades in the classroom.

Speaking as images flashed on the screen, he gave a sweeping book list that included the history of Black cowboys, Black inventors, and centuries of social justice fighters. Books on the list included a history of Nat Turner’s rebellion, A Rose for Emily, Best Shot In The West, MARCH, In A Class of her Own, Supah Sisters and Black History for Beginners.

“You can’t find out about American history and leave us out,” he said.