Downtown | Juneteenth | Arts & Culture | Youth Arts Journalism Initiative | Arts & Anti-racism

Participants at the Liberation Table. Abiba Biao Photos.

“It is our duty to fight for our freedom,” I said.

“It is our duty to fight for our freedom!” participants responded back.

Arms locked, heads held high, participants stood around the table to read aloud Assata Shakur’s poem through a call and response.

“It is our duty to win,” I said louder.

“It is our duty to win!” participants responded back.

“We must love each other and support each other.”

“We must love each other and support each other!”

“We have nothing to lose but our chains.”

“We have nothing to lose but our chains!”

"With each verse of the poem, our voices merged into a powerful roar.

This was just one of the exercises people participated in at the Liberation Table last Saturday on the New Haven Green, a gathering for Black people of the African Diaspora to reflect upon the legacy of Black history and impacts of colonization.

The project is an initiative of Hillary Bridges, the former executive director of Students for Educational Justice (SEJ), and Cooperative Arts & Humanities High School graduates Samantha Sims and Benie N’sumbu. This iteration was timed to coincide with Juneteenth, which recognizes the emancipation of enslaved Black people in Galveston, Tex. on June 19, 1865.

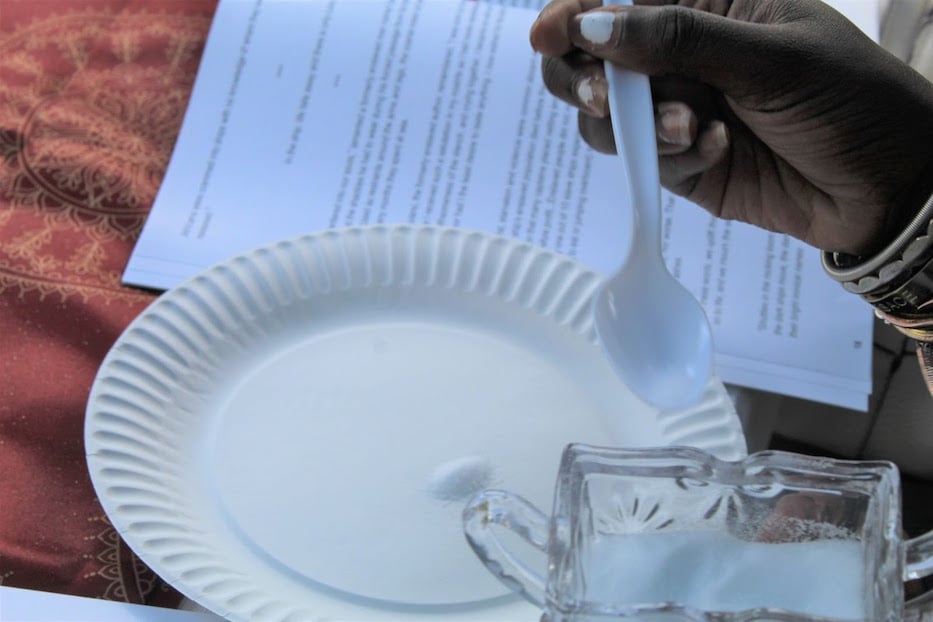

The salt bowl being passed around.

Bridges was first inspired to build the event after attending a Passover seder several years ago. Like the Haggadah that guides Jewish people through the story of the exodus from Egypt, Liberation Table comes with a guide with poetry, narrative, and song. A former member of SEJ, N’Sumbu joined the project in June 2020.

“This kid was reading from the Haggadah, and he was reading like ‘And we were slaves in Egypt!’ and he was proud, and I was like ‘Wait a second. Why don’t we do that?’” Bridges recalled in an interview over Zoom earlier this year. “We were enslaved and we don’t do that. And that, and my anger about not learning history, is what helped me start [this].”

In building a guide, Bridges, Sims and N’sumbu also drew inspiration from Keti Koti Tafel, a Dutch initiative dedicated to unearthing and discussing the Dutch history of enslavement. Unlike that project, Liberation Table is organized by and meant primarily for Black people. While this iteration was open to everyone, non-Black participants were asked to respectfully spectate and leave the floor open to empower Black voices.

Liberation Table is held twice a year, once in February in celebration of Black History month and again on Juneteenth to mark the emancipation of enslaved Black people. Earlier this year, organizers piloted a version at Jazzy’s Cabaret on Orange Street. This one, held on Juneteenth eve, took place on the New Haven Green.

Sims and N’sumbu, co-founders of the Liberation Table, led this gathering. They kicked it off at 1:30 p.m. with an overview of the event along with participants introducing themselves around the table.

Everything was set on the table with intention, with the table itself representing the overlap and shared values of Black tradition and cultures. The central items included a salt bowl, liberation cup and candle, each signifying a different part of Black history.

Participants put a scoop of salt onto their palms or plates. As attendees passed it around, each person dipped their finger into their small pile of salt and lifted it into their tongue to taste. This represented the challenges and toils the ancestors faced and struggles of slavery.

Top: Pamela Sims lights the candle. Bottom: David Sims sprinkling water around the table.

Top: Pamela Sims lights the candle. Bottom: David Sims sprinkling water around the table.

Next was the liberation cup, which represented an offering of gratitude to the ancestors for their efforts and labor throughout the year. In a nascent tradition for the project, the eldest member of the gathering sprinkled water from the liberation cup on the North, South, East and West of the table to make the offering reach all the ancestors. The process of libation also cleansed the ground.

Pamela Sims stepped up to light the candle, which was required to be lit by the second eldest person in attendance. One candle was illuminated to represent the remembrance of Black heritage is a guiding light and the traditions of the ancestors illuminating the present. A second candle was lit by the eldest person in attendance to show how the knowledge of heritage can spread and improve the lives of others.

As the candle burned the table cried "Ase!," a word which comes from the Nigerian language Youba. Similar to “amen,” it is used as a proclamation of blessing with the literal definition being “may it be so.”

Participants then reflected on the impact of enslavement by reading about the Middle Passage from the Liberation Table Guide, a booklet with curated passages about Black tribulation and agenda of the event.

Mequitta Ahuja sharing her cultural artifact.

There was also time for participants to share cultural artifacts that represent their history. Painter Mequitta Ahuja showed off her historical documents from Swarthmore College containing her family lineage. The document was a letter from a Quaker who were helping to emancipate Black people support free slaves. Through her research, she discovered that her great great great grandmother on her mother’s side was a white woman but lived her life as a Black woman.

Ahuja got into genealogy after her son was born with blond hair. Ahuja said she was taken aback by seeing his blond hair color because her identity—she is Black and South Asian—was tied to the constant rejection of Eurocentric beauty standards and association with whiteness. Learning that blonde hair is a recessive trait that was passed down from both parents, she dove into her family tree, building off of the research her grandmother had started in the 1950s.

To Ahuja, her son's hair color became a “physic focal point” and obsession to track down the root of this causation. She didn’t want her dissonance from whiteness to impact her relationship with her son, she said, and used this fact to face the impact colonization has had on herself, her identity, and family history.

"It was because of him [her son] being who he is, and he led me to the discovery of my answer,” she said. “And he led me back to my grandmother's work. I feel now a really deep acceptance and gratitude that things are as they are.”

The meal ended off with dessert to finish the afternoon on a sweet note. Attendees wound down from their deep conversations by reflecting on what they would take away from the Liberation Table

“I think about like how we’re going to unravel ourselves from the web of depression that’s so hard to remove yourselves, at least individually," N’sumbu said, remarking on the slow progression of social justice.

“Its really important to find representation and seek answers for things that you’re looking for internally. It’s like self discovery, and its something that you have to do yourself.” I said.

Our final exercise of the afternoon was to take three deep breaths. Breathing at the same pace, in sync, sharing the same breaths just as we did with our stories, trauma, and heritage.

“I hope that the Liberation Table has served as a reminder that we come from greatness and we contain reservoirs of power,” said Sims. “Thank you all again for being a part of this journey.”

And to that, we said “Ase!”

This piece comes to the Arts Paper through the fifth annual Youth Arts Journalism Initiative (YAJI), a program of the Arts Council of Greater New Haven. Read more about the program here or by checking out the "YAJI" tag. Abiba Biao is a newly-minted graduate of Achievement First Amistad High School and will begin her freshman year at Southern Connecticut State University in the fall.