Culture & Community | Education & Youth | Arts & Culture | New Haven Public Schools | Wilbur Cross High School

Kelvia Mitri-Meda and Adam Sharqawe. Lucy Gellman Photos.

Music filled the gymnasium as Kelvia Mitri-Meda made her way onto the floor, a glittering baton balanced in one hand. From the speaker system, the double-reeded wail of a zurna sang out over steady percussion. A knot of giggling high schoolers formed along one side of the room. Then without hesitation, student Adam Sharqawe lifted a black-and-white keffiyeh that had been around his neck, held out one hand, and stepped in to dance.

The scene was one of many at Wilbur Cross High School’s second annual Arabic Festival, organized by Arabic teacher Hanan Elkamah and held in the school’s large gymnasium last Friday. Over five hours, both teachers and students focused on sharing culture as a way to smash stereotypes, teach tolerance, and bridge long-existing cultural barriers. Hundreds of students attended.

The festival received support from Qatar Foundation International, which has also funded New Haven high school summer language learning programs and a virtual language exchange with refugees. Around the gymnasium, activity stations included Middle Eastern cuisine, henna, dance, and a table where students could learn about and try on hijabs.

Festival organizer and Arabic teacher Hanan Elkamah.

“I feel like I have to spread this knowledge, and have them [students] notice cultural similarities more than differences,” said Elkamah, who immigrated to the United States from Egypt 26 years ago and has taught at Cross for four years. “People don’t always know. They don’t always have the knowledge—so we try to learn about each other. Not to change each other. ”

Elkamah launched the festival in 2018, during her first year of teaching at the school. By then, the New Haven Public Schools district had offered Arabic for 11 years, and grown the program considerably after receiving a federal grant for critical language education in 2010. In her four years at Wilbur Cross, Elkamah’s course load has grown to roughly 110 students. This year, many of her students are young people who arrived as refugees from Afghanistan, and speak Pashto.

For her, the work is as personal as it is professional. The mother of three, Elkamah decided to go into education several years ago, when her youngest son started attending King Robinson School and she came in to speak with his class. She loved talking about her cultural background, busting through stereotypes one story at a time. After earning her teacher’s certification, she began teaching at Mauro Sheridan Interdistrict Magnet School, and then transferred to Wilbur Cross four years ago.

Amel Elnaw, now a student at Colby College in Maine, came out to volunteer.

In her own classroom, she has found that misunderstandings of the Middle East and wider Arabic-speaking world abound—particularly when it comes to women who choose to cover their hair. Elkamah wears a hijab, the headscarf worn by Muslim women across the globe as a symbol of modesty and faith. So do several of her students, whose families hail from New Haven, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Syria, Afghanistan, and Palestine among other places.

Often, she finds that talking openly about stereotypes—for instance, why some women choose to cover their heads, and others do not—leads to mutual respect among her students.

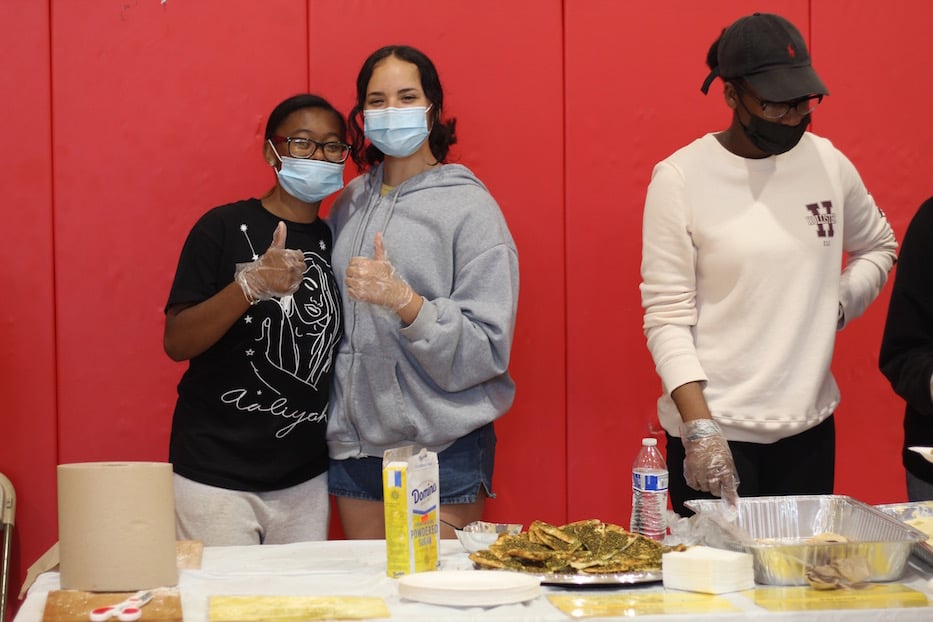

As students set up stations across the room, cross-cultural understanding appeared to be the order of the day. To the right of the gym’s large double doors, sophomores Dream Ford and Daleska Zeas turned the food station into a neat assembly line, handing out plates of golden, still-warm paratha, fresh hummus, pita and flatbread with a thick, seed-studded dusting of za'atar. Every few attendees, they spotted a classmate and waved enthusiastically, beckoning them over to try the food.

Dream Ford and Daleska Zeas.

Zeas, whose family is proudly Ecuadorian, said she never intended to take Arabic—she was “just put” in the class at the beginning of the year. Originally, she balked at the language, worried that it would be too hard for her to learn. But as she stuck with it, she fell in love with the cultures, foodways, and rich traditions about which she was learning. Now, she has dreams of traveling to the Middle East to experience it for herself.

“I want to learn about it,” she said.

Beside her, Ford lifted a heaping spoonful of hummus onto a classmate’s paper plate. A student in Spanish I this year, she signed up to volunteer at the festival after learning about it from her peers. “It’s exciting because there are traditions that are celebrated and there are things here that I’ve never tried before,” she said.

Raghad Orabi and Rawan Alhafez.

Halfway across the gymnasium, senior Raghad Orabi linked arms with Rawan Alhafez, a junior at Hill Career Regional High School, and strolled over to a large poster of a camel standing before the pyramids. Born and raised in Syria—Alhafez in Homs and Orabi in Damascus—both came to the U.S. as refugees in 2016. In school, they’ve found that their peers know very little about their home country. What they do know is usually violence and civil war.

“Today is all about our culture,” Alhafez said. When she did a presentation on Syria her freshman year, her classmates were surprised to learn a history that went back millennia, far beyond the Syrian Civil War and U.S. military presence in the country. Both called the festival a chance to educate their classmates.

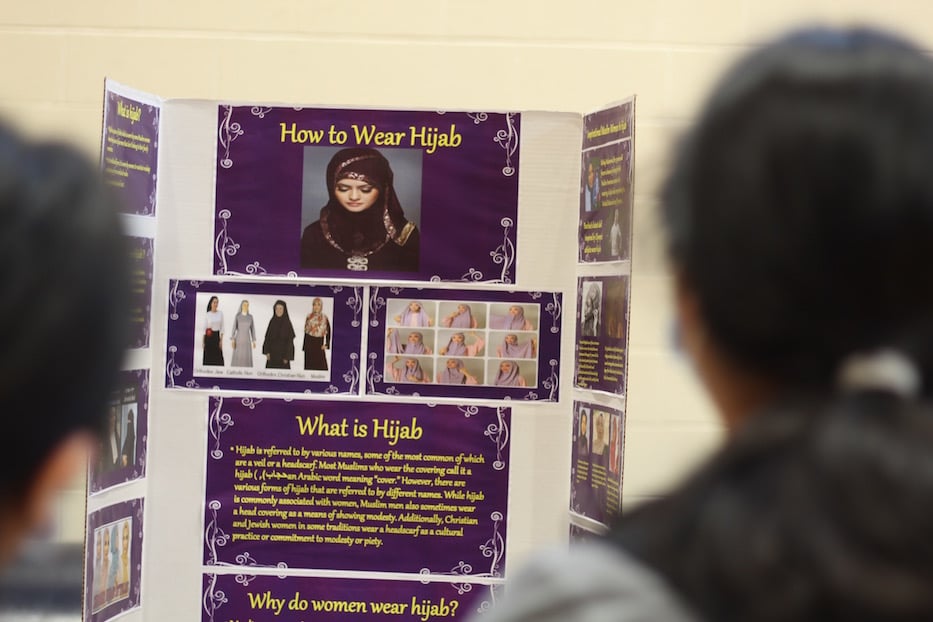

Alhafez motioned over to a nearby table where students could read about the practice of wearing hijab, glad to see that dozens of Cross students were stopping by and taking time to absorb the text. At the top of the poster, a woman looked toward the ground, her purple-red hijab criss-crossed with gold designs. Below her, several scarves lined the table. Throughout the day, a few students tried them on, slipping them over their hair.

Wazhma Maseeri.

Walking by in a sweeping blue dress with silver and white trim, Cross junior Wazhma Maseeri took note of the station, and then made a beeline for a giant photograph of a lamp on a velvet blue background. Born in Afghanistan, Maseeri and her family lived for years in Pakistan, and then came to the U.S. in 2014. She said that Friday was special to her, because “I want people to know more about my culture” than war and civil unrest.

Currently, she is deeply alarmed by the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, and said she prays for those affected and still in the country.

“We’re so embracing,” she said. “Our food is delicious.” She added that she’s been taking Arabic, now the fifth language that she can speak alongside Pashto, Urdu, Dari, and English.

At the henna station nearby, students Bibi Aisha Khogyani and Rooqia Mangal (both asked not to be photographed) worked methodically, hands steady as Arabic and Pashto lettering, large flowers, and intricate webs bloomed across their classmates’ hands and arms. Both originally from Afghanistan, the two praised the festival for fostering cultural awareness among their classmates. A black, red and green striped Afghan flag sat nearby.

“In New Haven, I don’t want to be mean, but students, they just don’t know about other cultures,” said Mangal, a sophomore who came to New Haven from Afghanistan in 2019. “I think they should learn about other cultures.”

For instance, she said, she gets questions about her hijab almost every day. While she tells her peers that “we feel very special in the hijab, we feel very unique,” she doesn’t have a sense of how many of them understand that it’s her choice to wear it. Between thoughts, she squeezed a silver tube of red-brown henna paste carefully, placing a dainty heart beside the calligraphic scrawl.

A little after 1 p.m., both looked up and smiled as music filled the space. Mitri-Meda, the founder and head of the Middle Eastern Dance Academy of Connecticut, glided onto the floor in head-to-toe red and sparkling heels. Atop her head, a silver candelabra called a Shamadan remained fixed, impossibly, in place.

To the shrill cry of the zurna, she held her hands out to the student audience, an offering. Hand drums and hollow, echoey yarghul pulsed through the space. As her hips began to undulate, each movement isolated, students cheered and mimicked the movements from the sidelines. The silver sequins and fringe on her coin belt sang and rattled.

Sharqawe, a Palestenian student who had been quiet on one side of the gym, found his moment and stepped in. Mitri-Meda smiled, and held out a hand. Soon, a human chain had formed, dancing toward the center of the gym. She later said that she sees teaching dance as transformational, because the art form helped her accept her own body.

After the music had ended, Sharqawe said that he was grateful for the festival as a chance to talk about his upbringing and culture. Born in Nazareth in the North of Israel, Sharqawe moved to New Haven with his family in 2016, when an older sister got into Yale. Before he left his home, he said, he felt that fellow Israelis directed racism at him and members of his family because they were Palestinian.

There are currently about 2 million Palestinian citizens of Israel, according to the Institute for Middle East Understanding. But when Sharqawe opened up about his background in New Haven, students responded with blank looks, or asked him if he was talking about Pakistan. When he started taking Arabic with Elkamah, he said he was relieved that he didn’t have to explain himself. He said he was thrilled to have the festival at the school.

"Middle Eastern dance made me love myself and really accept my body," Mitri-Meda said.

“I’m willing to bet that less than one percent of Americans know what’s going on [in Israel and Palestine],” he said. “No one ever talks about it. I think this [the festival] brings so much light to a lot of our culture that people don’t really know about.”

Back inside, Amel Elnaw was cleaning up as 2 p.m. dismissal drew near. Now a student at Colby College, Elnaw volunteered for the event after hearing about it from her mom, a teacher at Benjamin Jepson Magnet School. Growing up Muslim in West Haven, Elnaw said that she faced constant ignorance, from inside her school to public places where she went in a hijab. People struggled to square how she could be Muslim, hijabi, and American. At the festival, her presence is a chance to educate people.

“People would look at me and be like, ‘Do you know English?’ And I would be speaking to them in English,” she recalled. “This is to inform people about other cultures. Our cultures are so different, and no one has bothered to know the history.”

For more from the festival, watch here.